The second startup that I have worked on, MacroFuel Food, closed its doors in April 2017. My experience with MacroFuel built upon my learnings from my first startup, daapr with additional lessons and new situations that ultimately evolved my understandings of entrepreneurship and of products. I worked on this startup with Gus Rietsema (CEO), Max Tave (CMO) and Charles Lee (CSO).

About MacroFuel

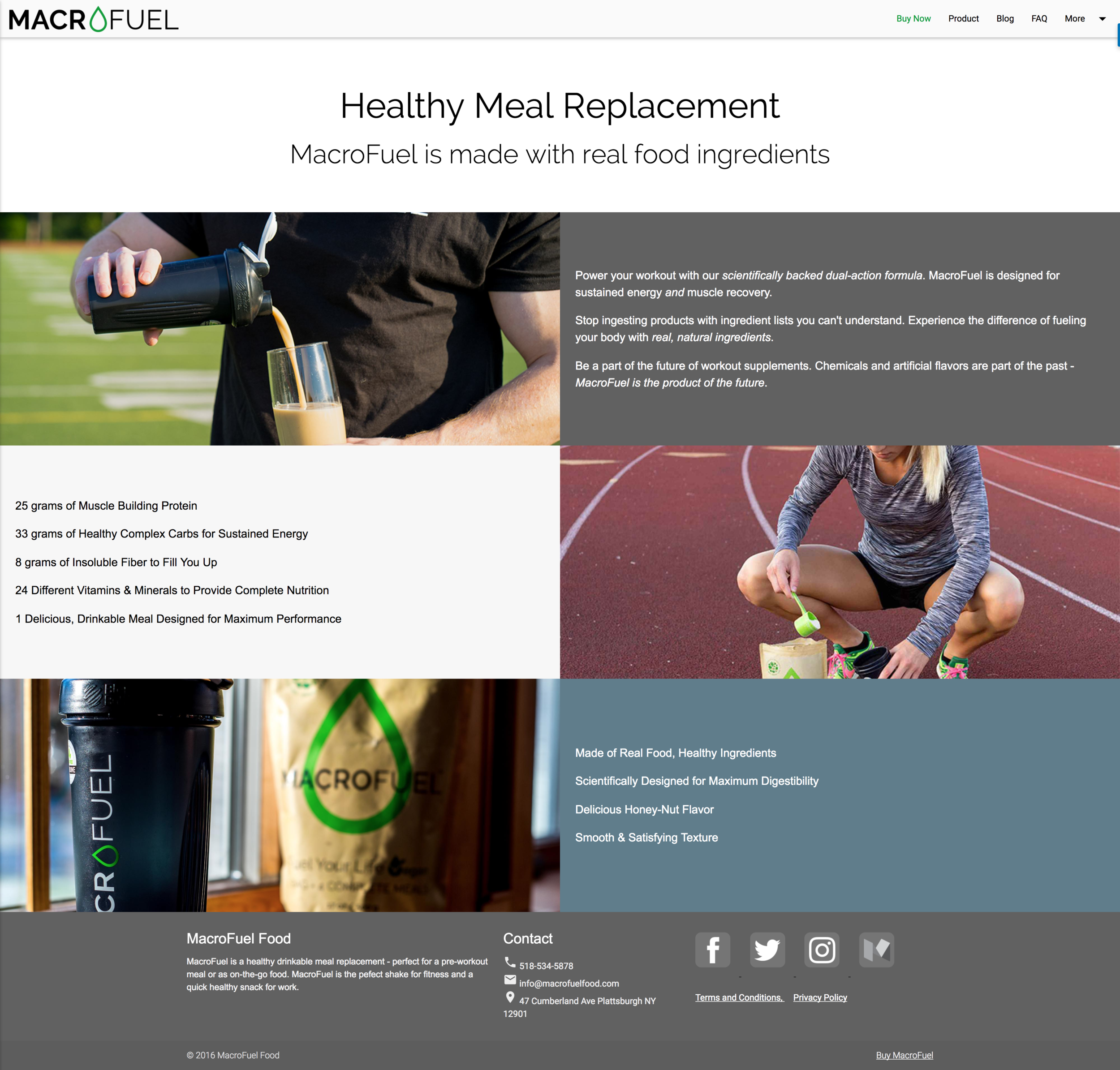

MacroFuel is a complete meal replacement in drinkable form. It is made with real food ingredients and has the of the nutrients of a well-balanced meal. It comes in a powdered form that is quick and simple to make, just mix the powder in ice-cold water, and you have a healthy, on-the-go meal in about 30 seconds.

MacroFuel started in a Cornell University Entrepreneurship class that Gus and Max took at the same time. The class involved coming up with a company idea, then building a business plan around it. MacroFuel came into existence as a response to companies like Soylent who had a good idea with meal replacements but had unfamiliar ingredients (like Methylsulfonylmethane) along with poor branding and multiple recalls. Building the business plan in class showed Gus and Max how making a meal replacement company actually was not as far-fetched as one might think.

The idea formed into a business plan, then into a real formula, then into a Kickstarter campaign, and finally into an online storefront.

I joined the company as it was preparing for the Kickstarter campaign. I worked to help build out the web presence for the campaign, and create the technology vision for MacroFuel post-Kickstarter.

MacroFuel was a very different venture for me than daapr. Daapr was a social media platform, and the entire focus was on technology. MacroFuel was a food product, and the company focus was primarily food and secondarily technology. We believed that technology could be the factor that gave us an edge against our competitors like Soylent, Ambronite, and Huel, so that is where I invested the bulk of my time and energy.

Technology Vision

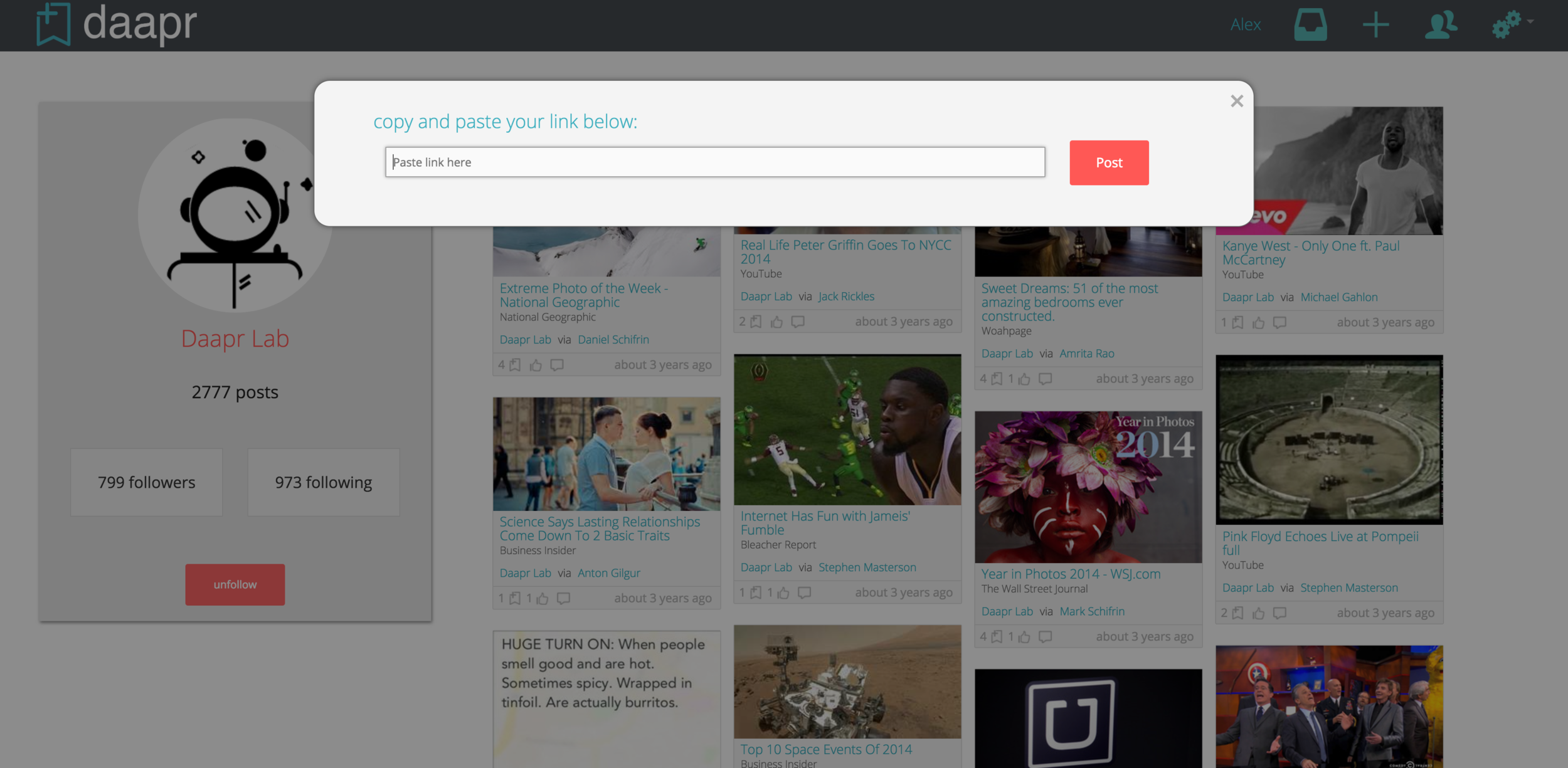

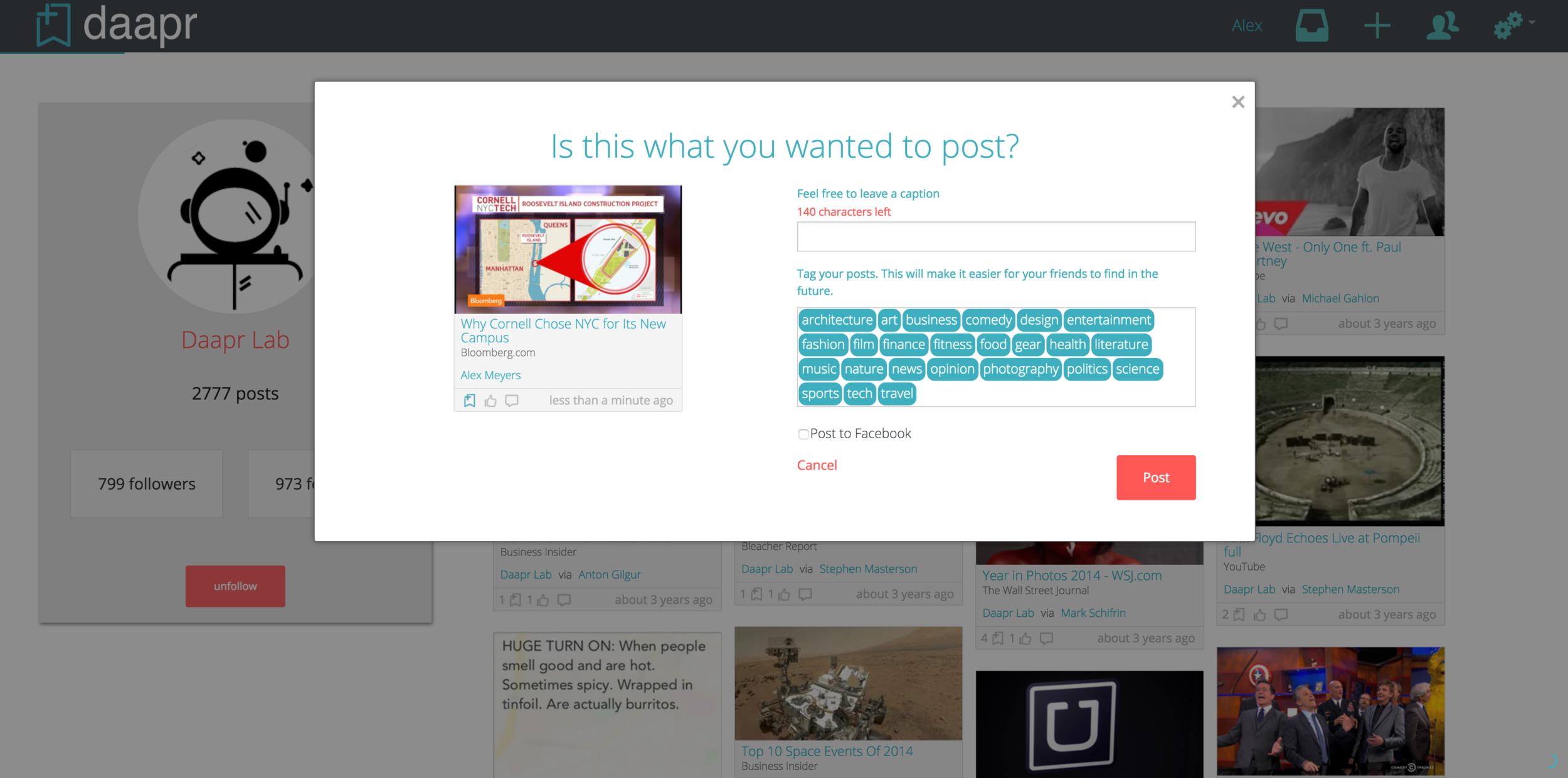

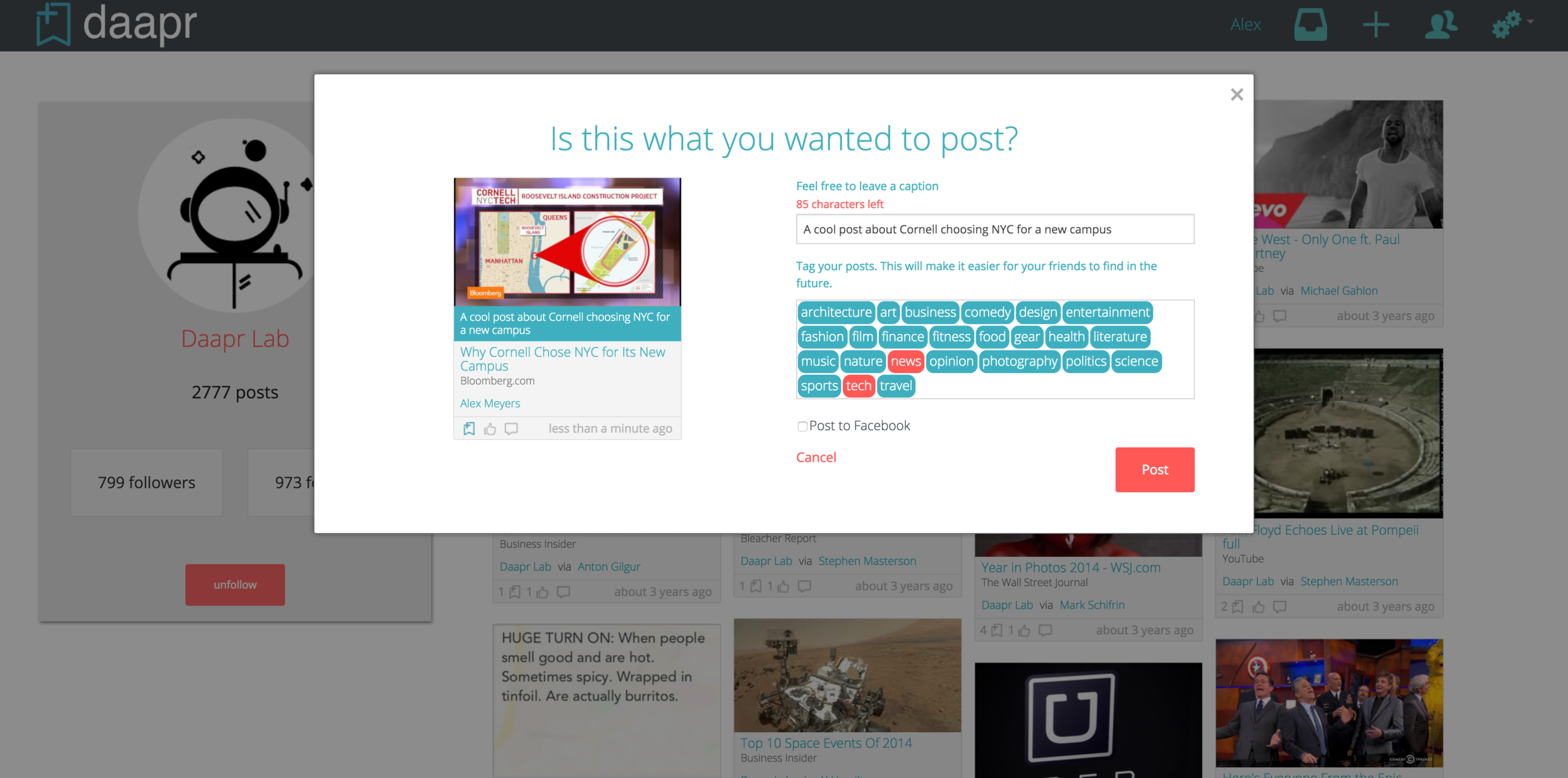

From a technology perspective, the vision was to create a seamless experience between the food product and technology experience in order to create an ecosystem that surrounded MacroFuel. The technology vision looked to include the following experiences: Company Website, Storefront, Administration Dashboard, Company Blog, and an Engagement Platform.

Company Website

This vision first started with a company website. The website was meant to describe the product, be an information hub for content that is related to the product, and be a marketing centerpiece. When customers, suppliers, and investors wanted to know more about MacroFuel, the company website was meant to be the answer hub for their needs. The site also was the company's first means of reaching out to customers. It pushed for visitors to subscribe to our newsletter and pushed discounts on first purchases to encourage sign-ups and purchasing.

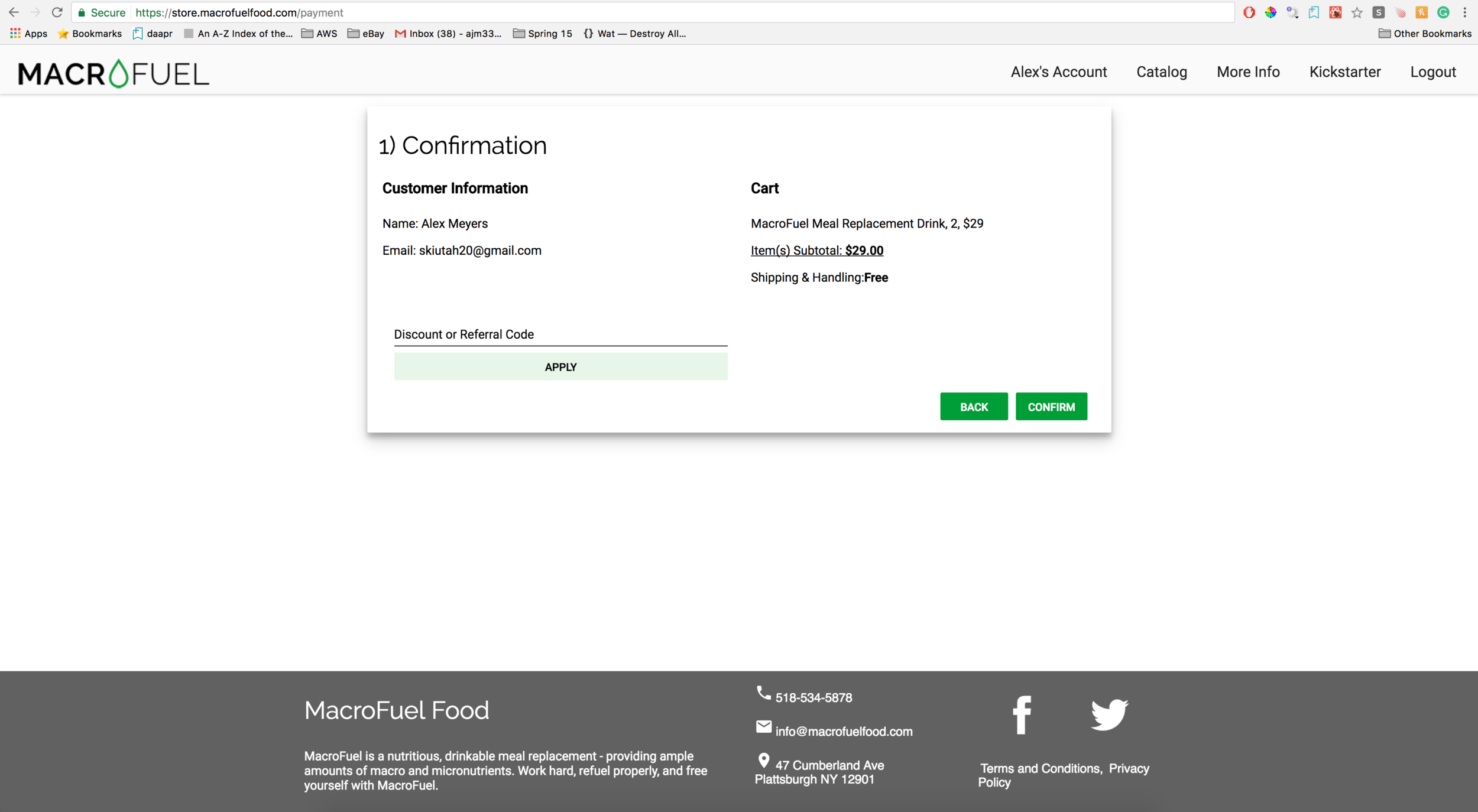

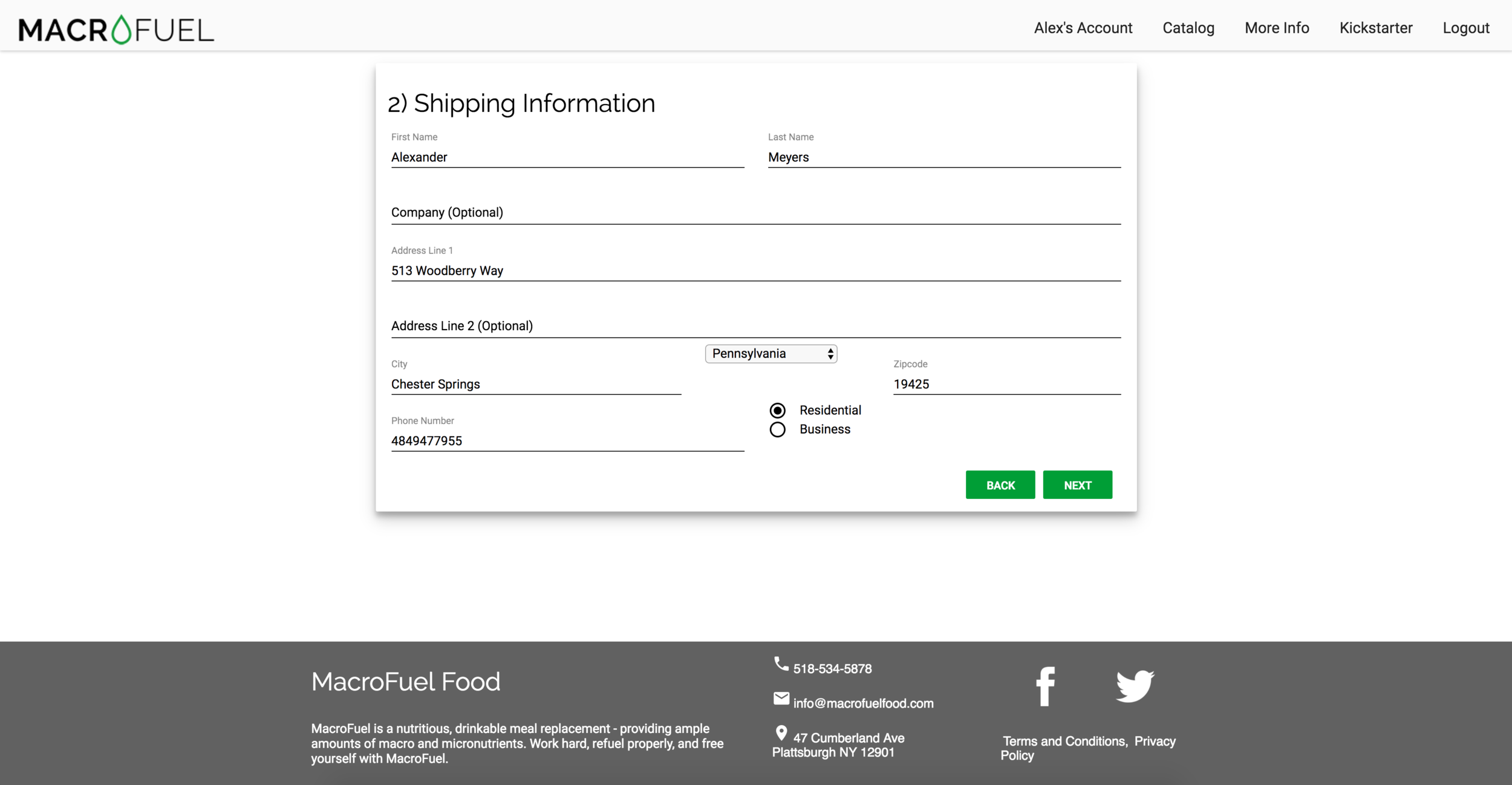

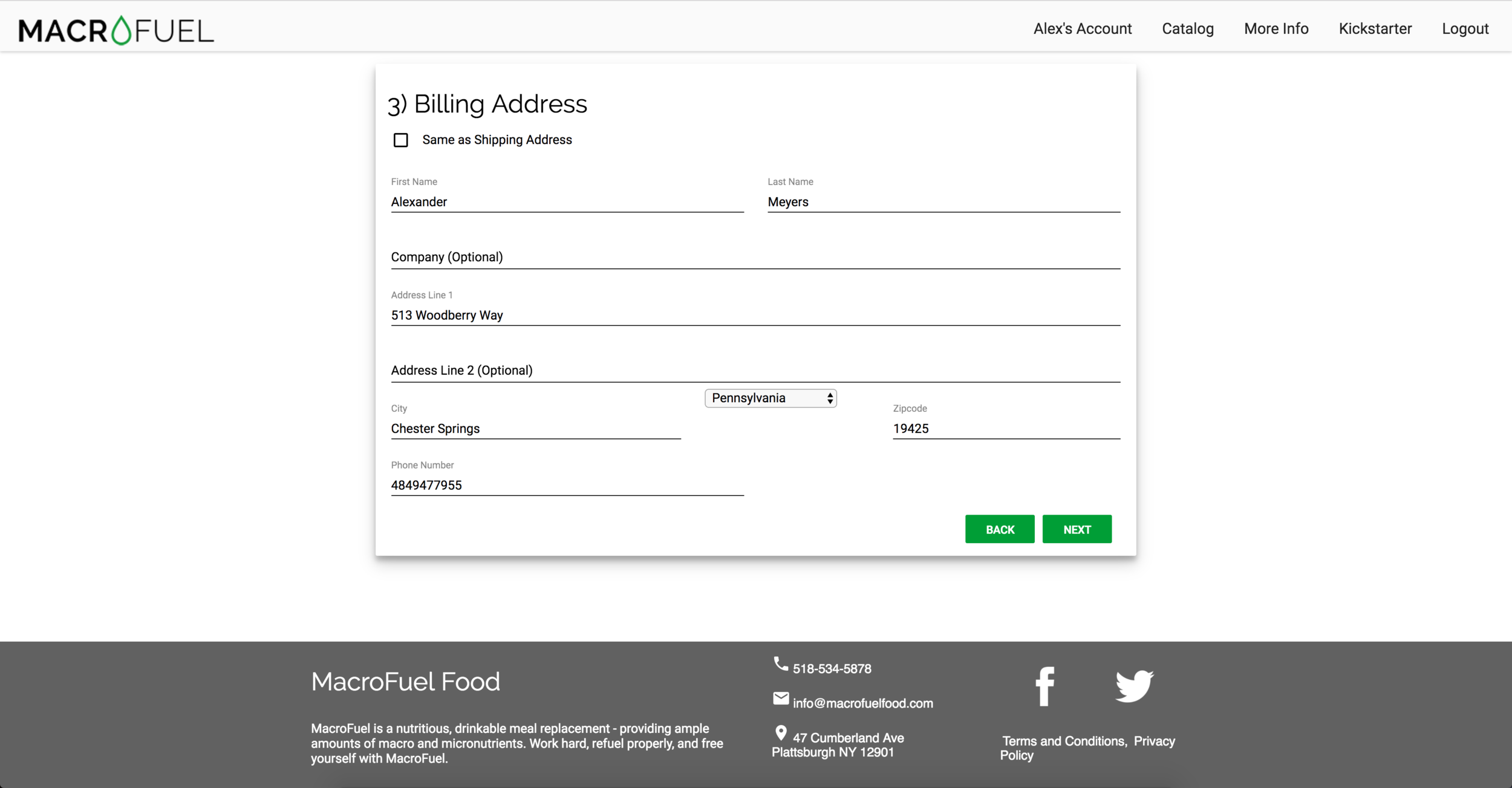

Storefront

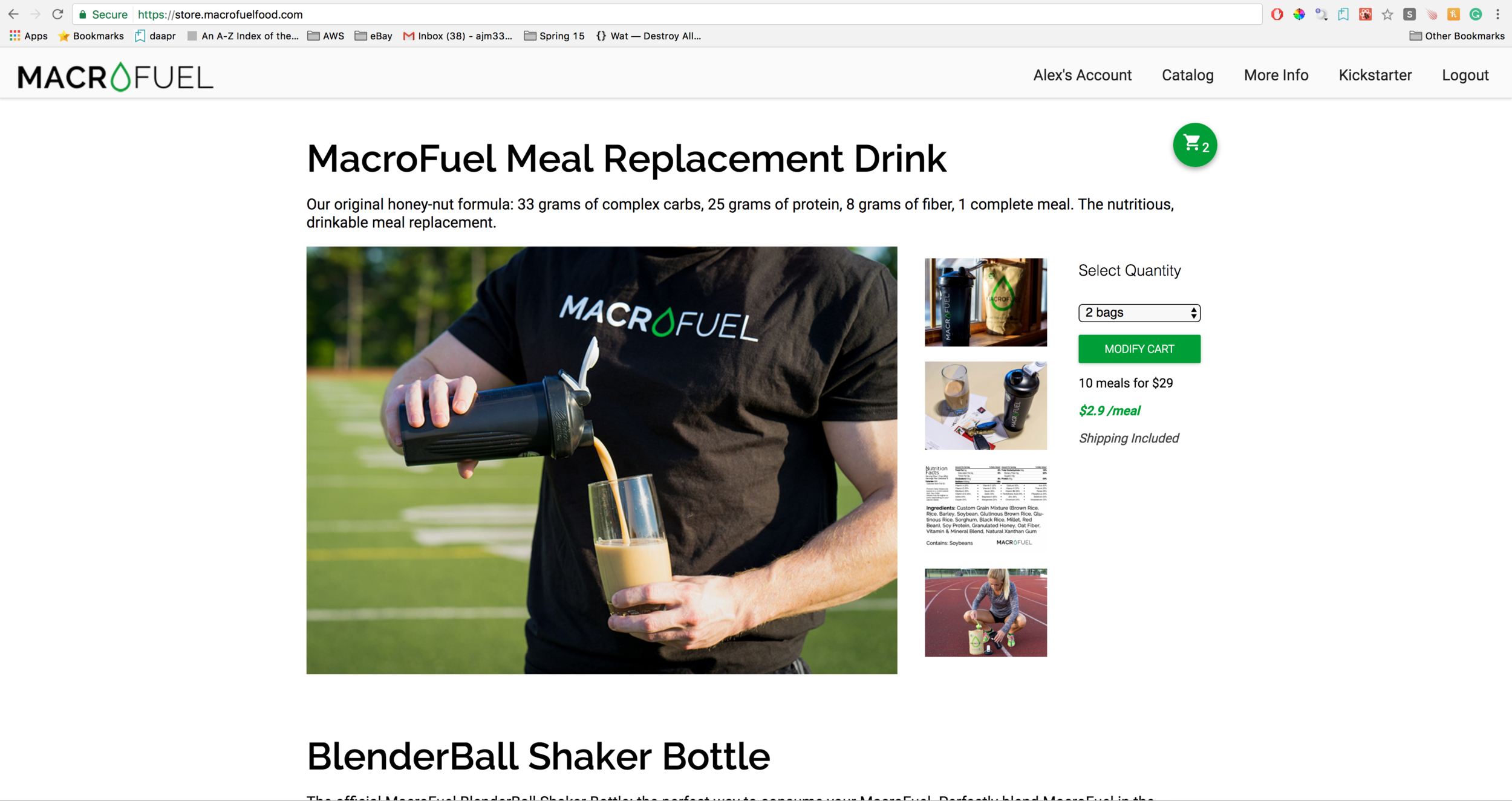

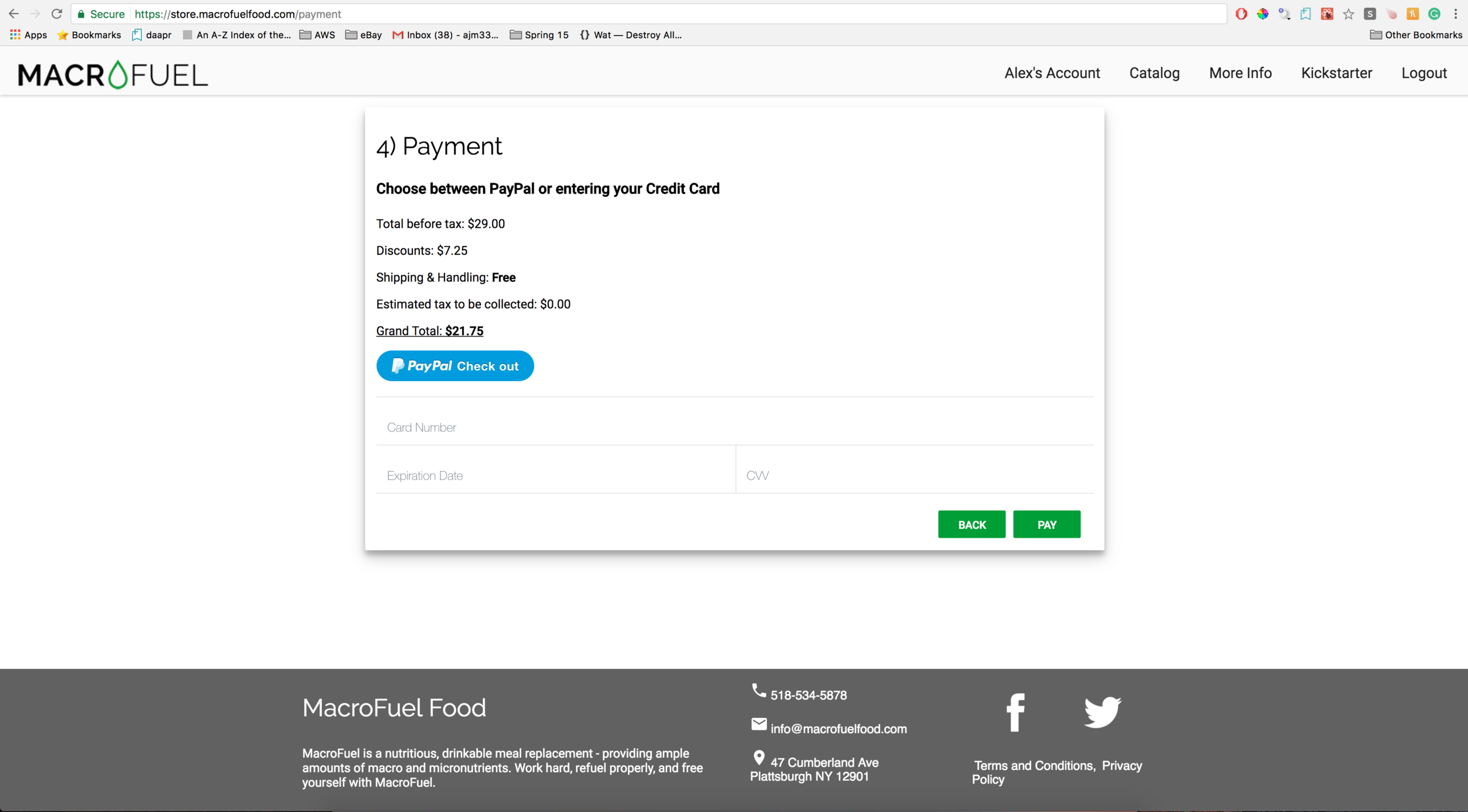

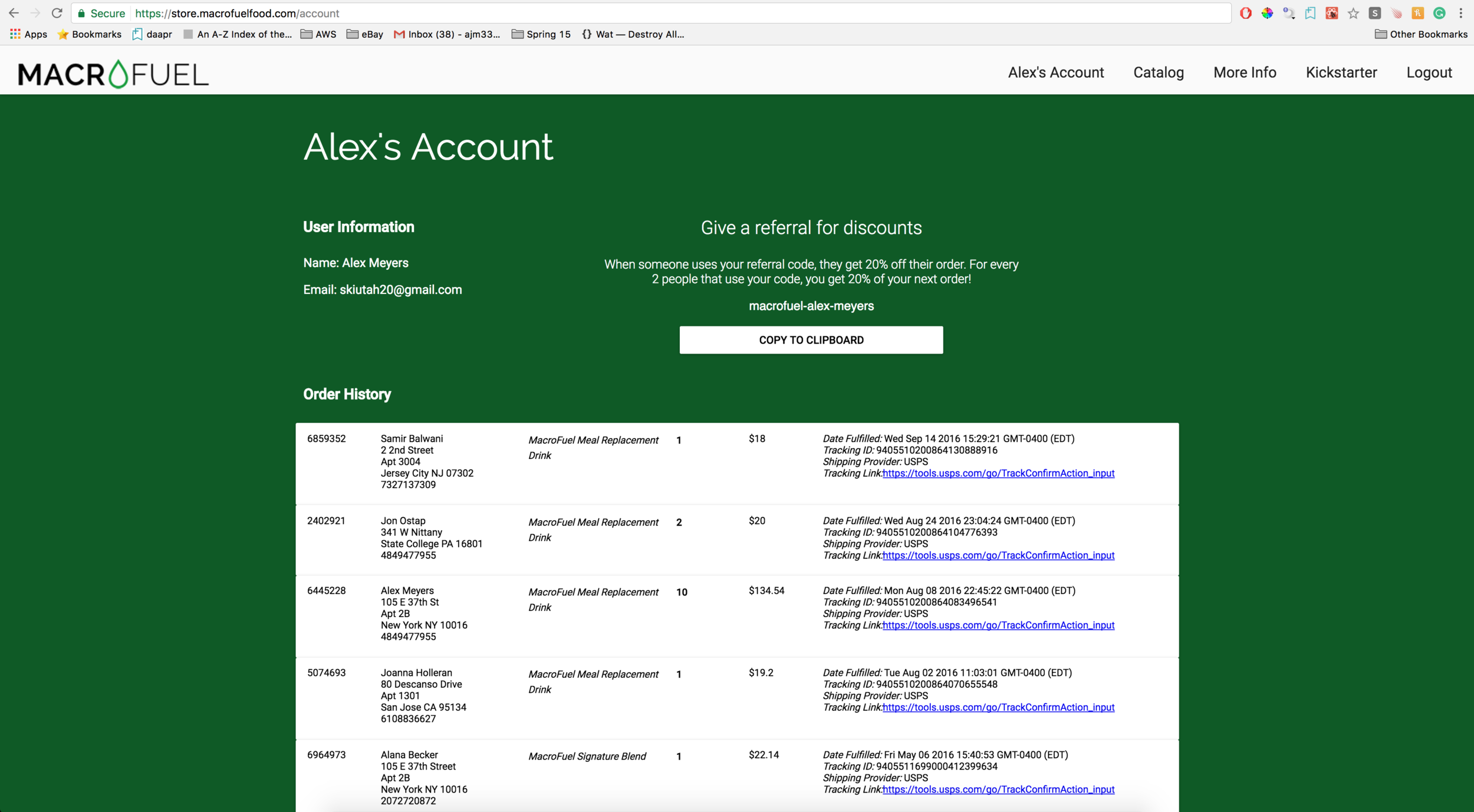

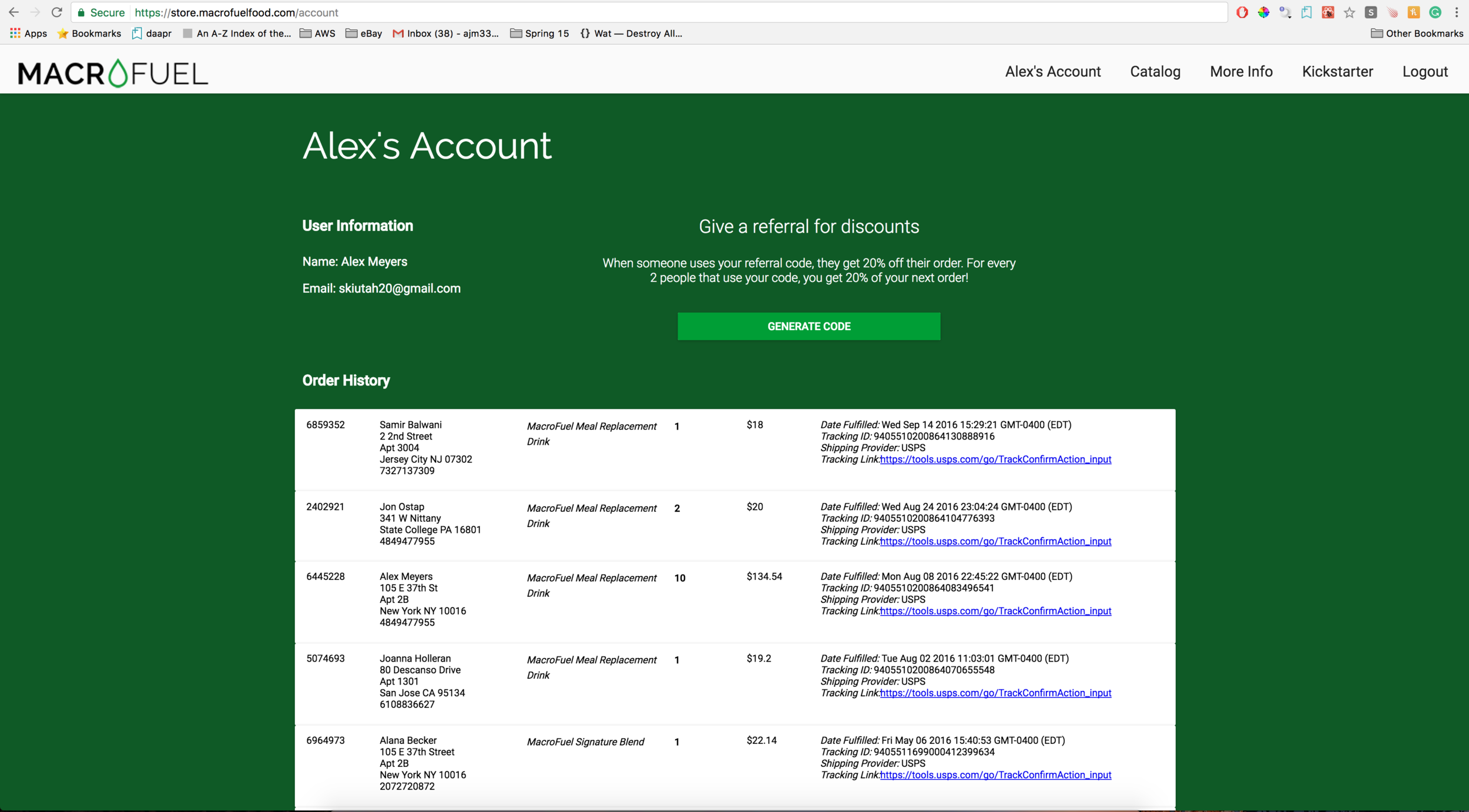

The Storefront continued the technology vision by presenting a simple, direct method for purchasing MacroFuel. The Storefront was optimized for mobile and desktop shopping in order to allow for purchases on all devices. It focused on putting product imagery in the forefront to create a visually engaging experience. Bulk discounts were also highlighted in order to encourage greater purchasing quantities for the potential savings. Checkout was broken down into simple steps to allow for streamlined purchases. PayPal integration also allowed for adding confidence for customers who were wary of a small, new brand. Finally, a profile page allowed users to check past orders, tracking shipments, and share referral codes. The referral process automatically applied a 20% discount for users at checkout who referred 2 new customers to MacroFuel.

Administration Dashboard

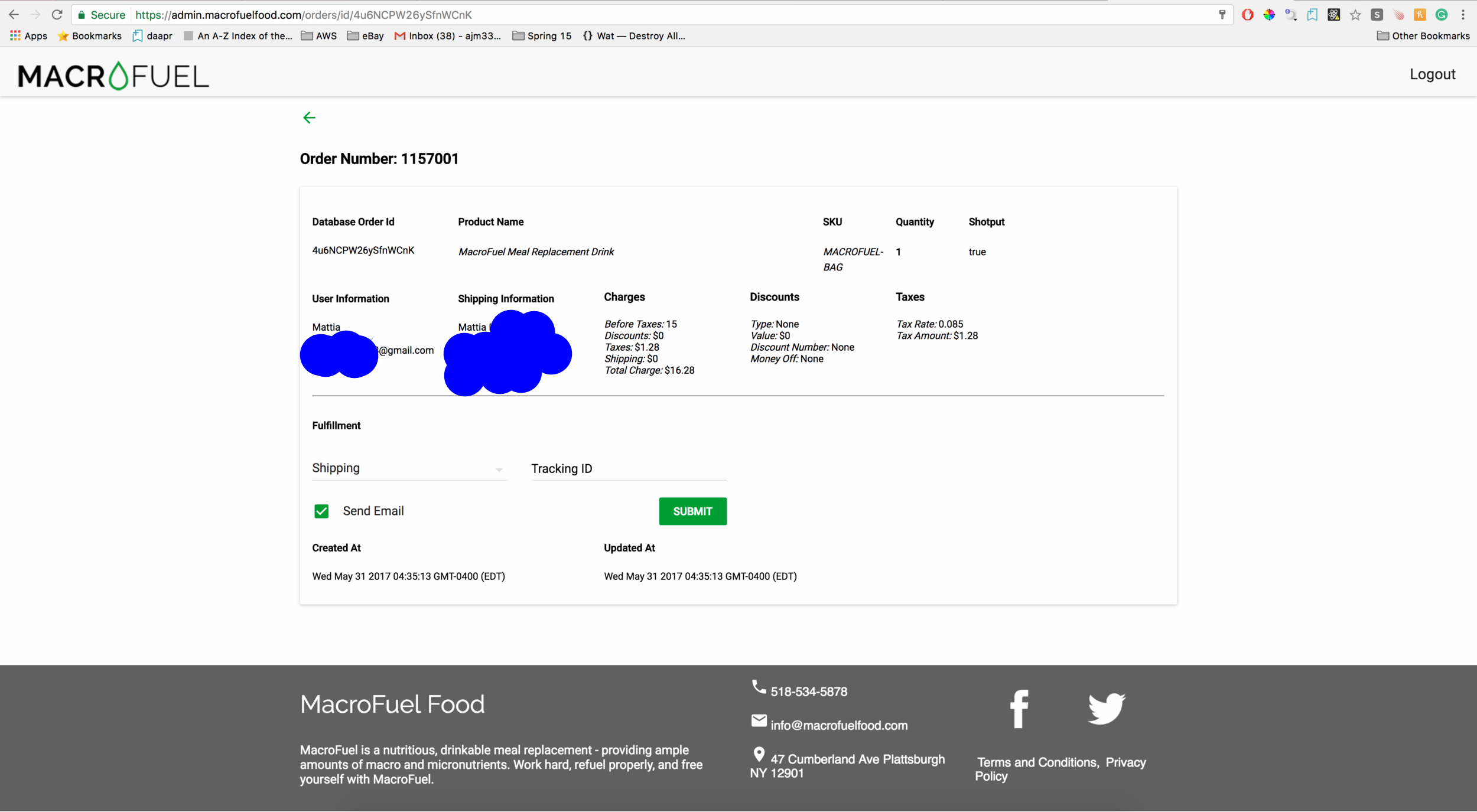

The Administration Dashboard allowed the team to track orders in the pipeline. Email notifications were automatically generated to the team when an order was placed. The Administration Dashboard also allowed for simple exportation of unfulfilled orders into CSV files for our storage and shipping provider Shotput to consume for fulfillment. The dashboard also allowed for various filters and searches based on an order's attributes. Finally, the dashboard sent automated emails to customers with shipping information once Shotput returned tracking information.

Company Blog

The Company Blog added to the technology vision by creating more MacroFuel content for customers to consume. The blog added new material to disseminate to customers and influencers to learn more about MacroFuel. It also fueled the company's Search Engine Optimization (SEO) strategy to acquire more traffic and potential customers through keyword strategizing.

Engagement Platform

Unfortunately, the Engagement Platform never did see the light of day. The vision for this product was to tie everything together and to help create an incentive for people to post on social media about MacroFuel. I had envisioned a feed in which customers could see and share MacroFuel content from every customer. The idea behind it was to build a rewards program that surrounded purchasing and sharing MacroFuel. Social media posts, referrals, and purchases would all earn points. (The referral program did exist through coupon codes, but the concept of points had not been created yet.) My goal was to help foster a community surrounding MacroFuel and turn our most avid customers into our top marketing agents. If we could incentivize and reward our customers for promoting MacroFuel, we could ideally have very cheap and successful marketing. The dream behind the Engagement Platform is the biggest reason why I custom built the Storefront and Company Website. I wanted to be able to create a shared user account that had a unified source of customer data across experiences so that we could always make our customers feel welcomed and in a single cohesive experience.

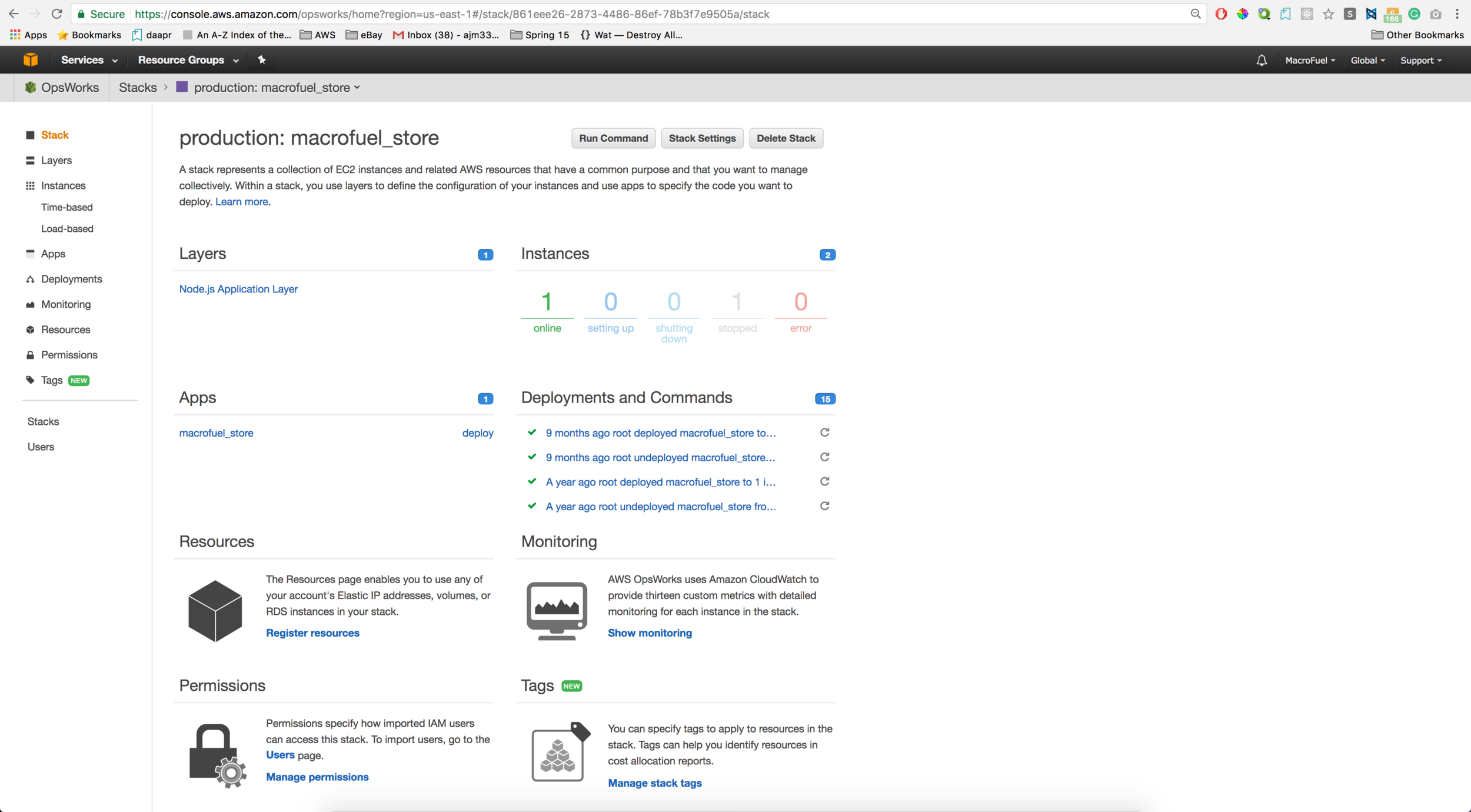

The Infrastructure

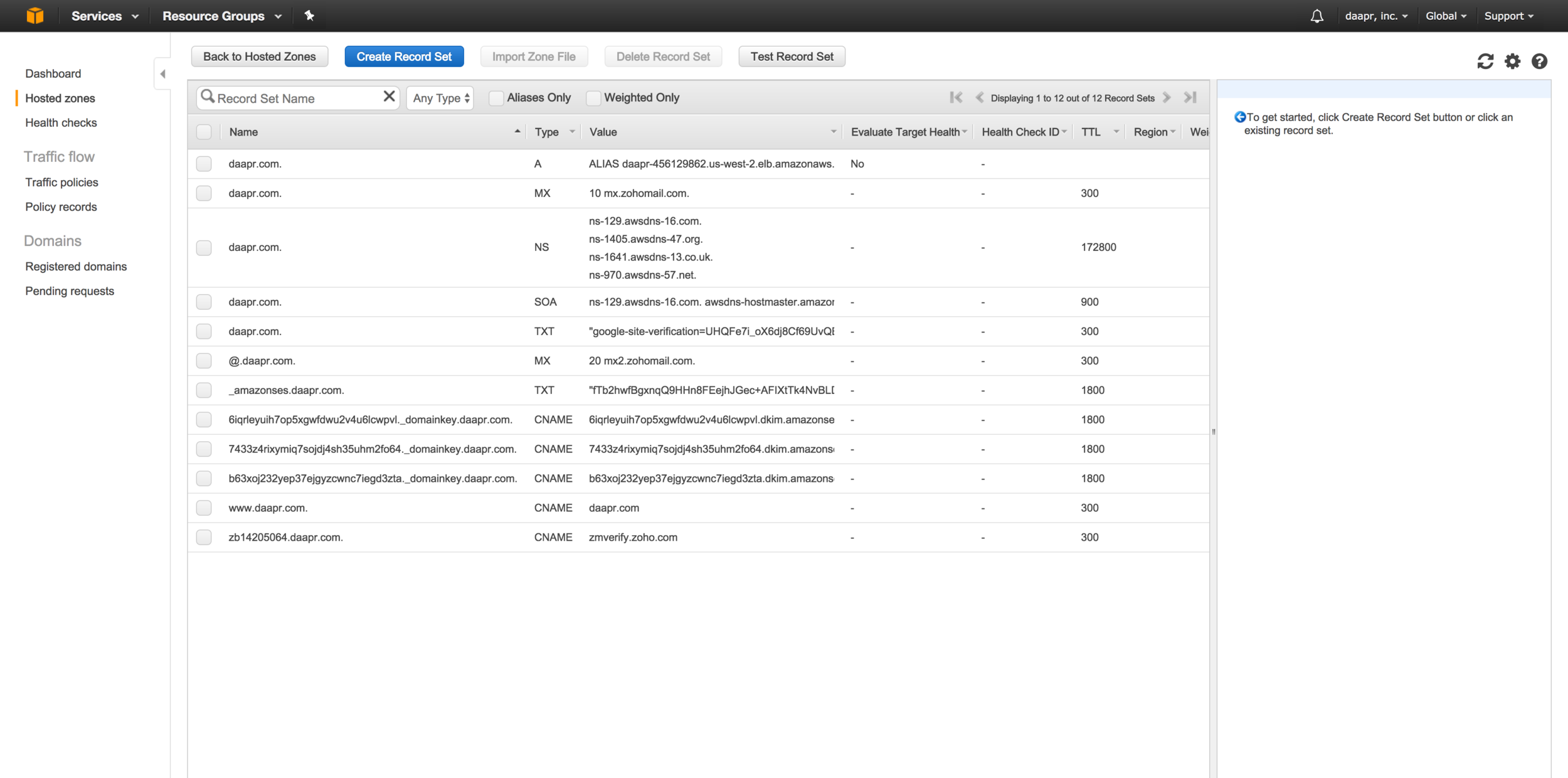

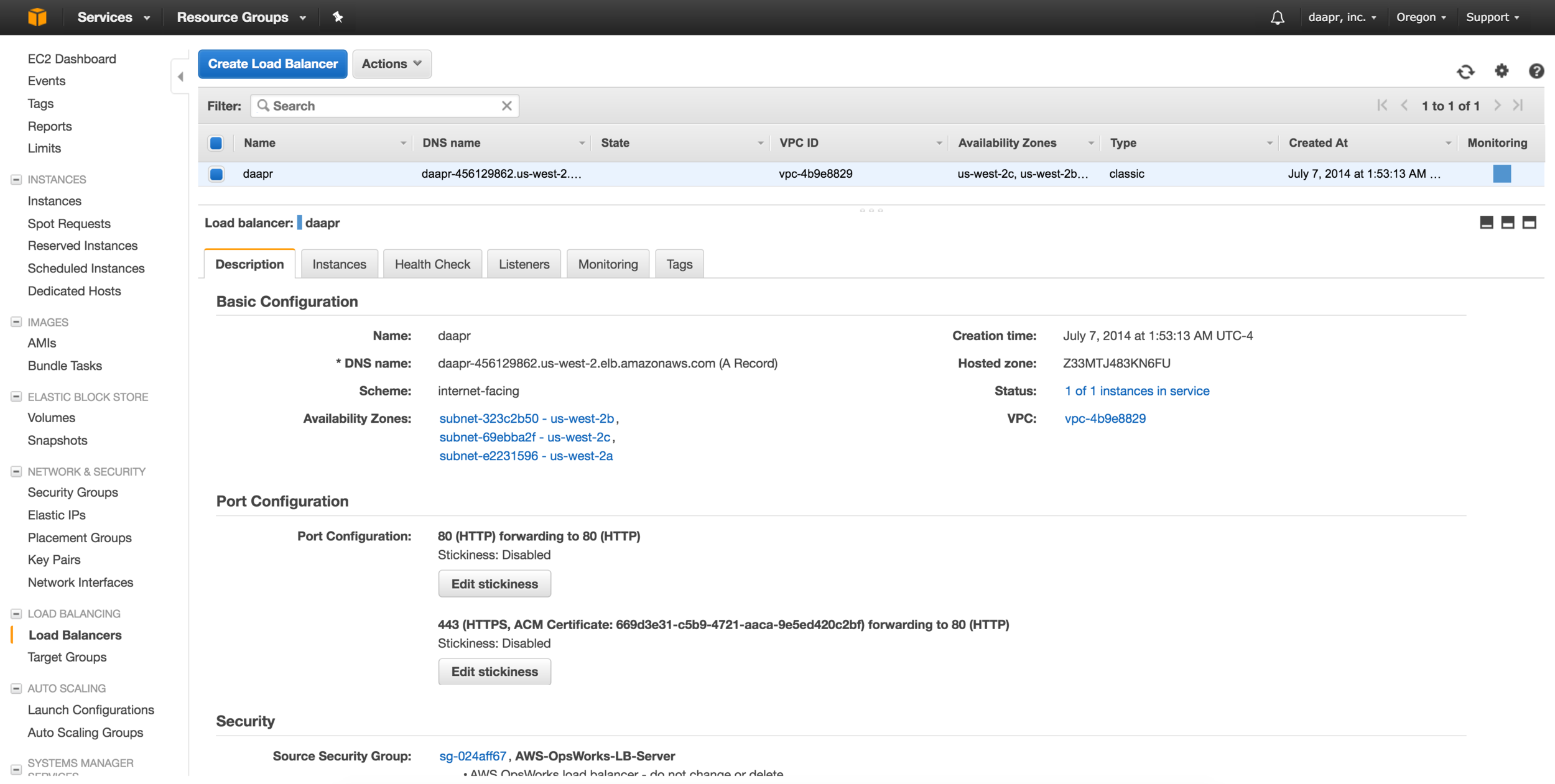

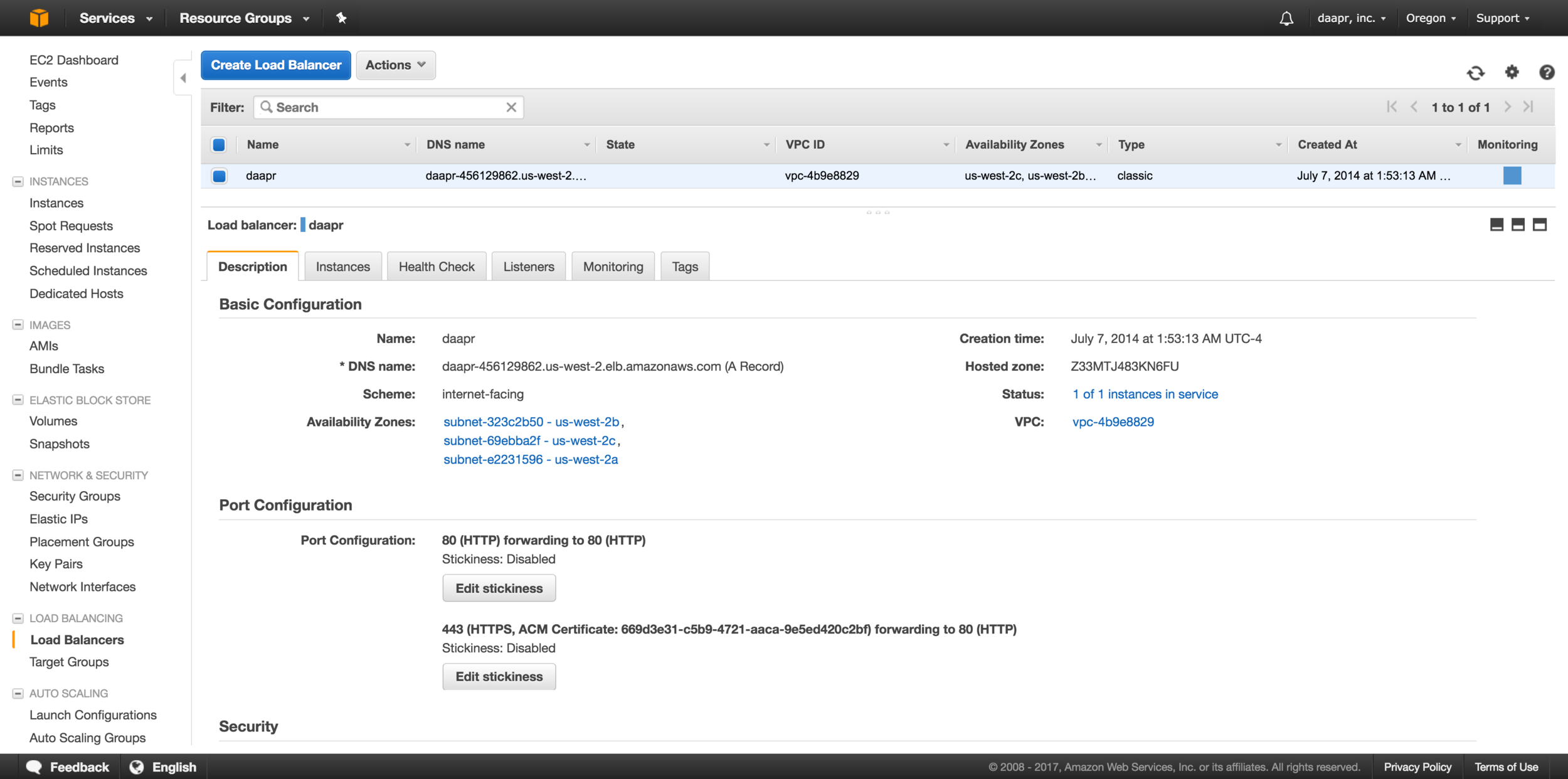

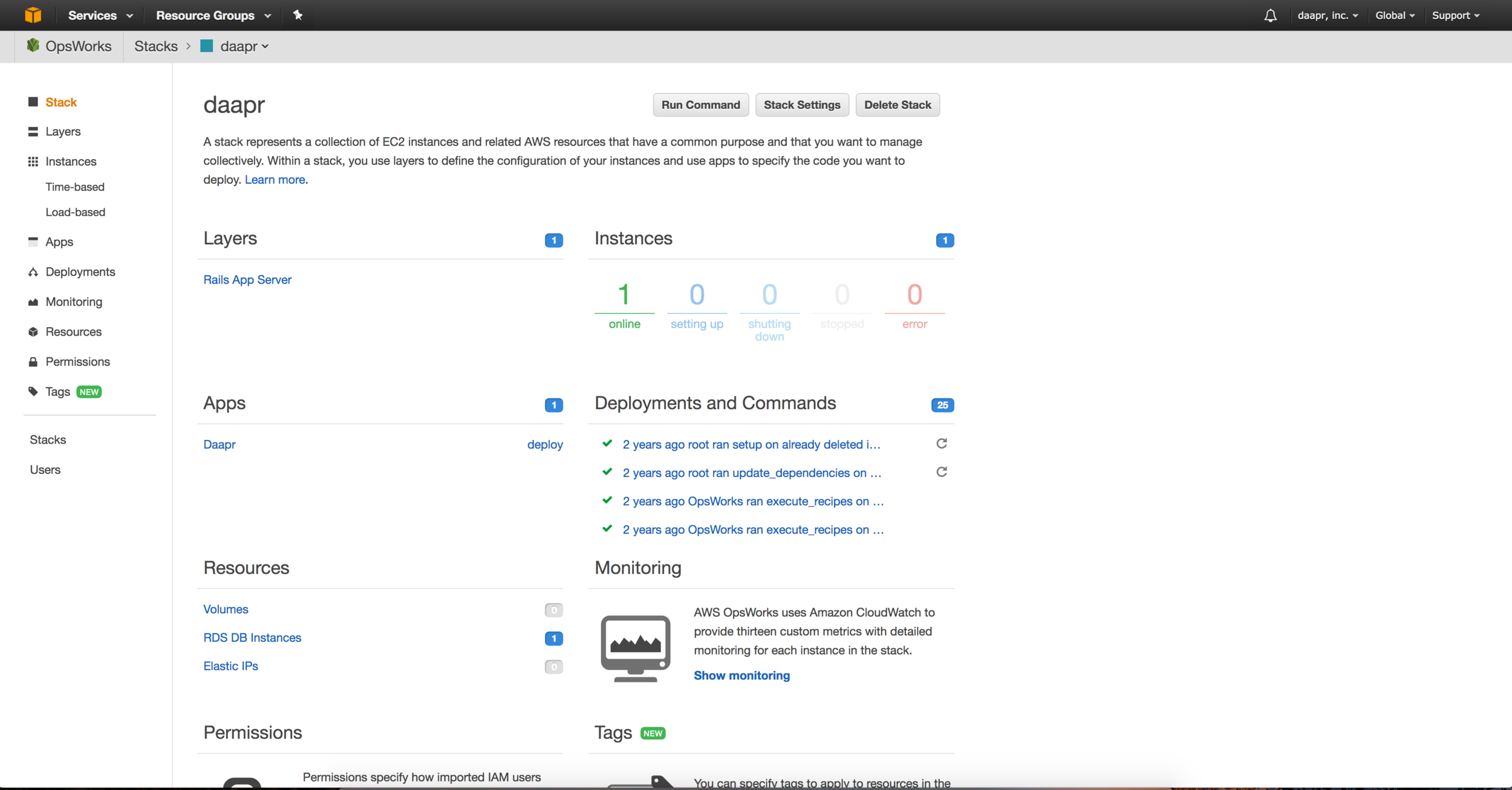

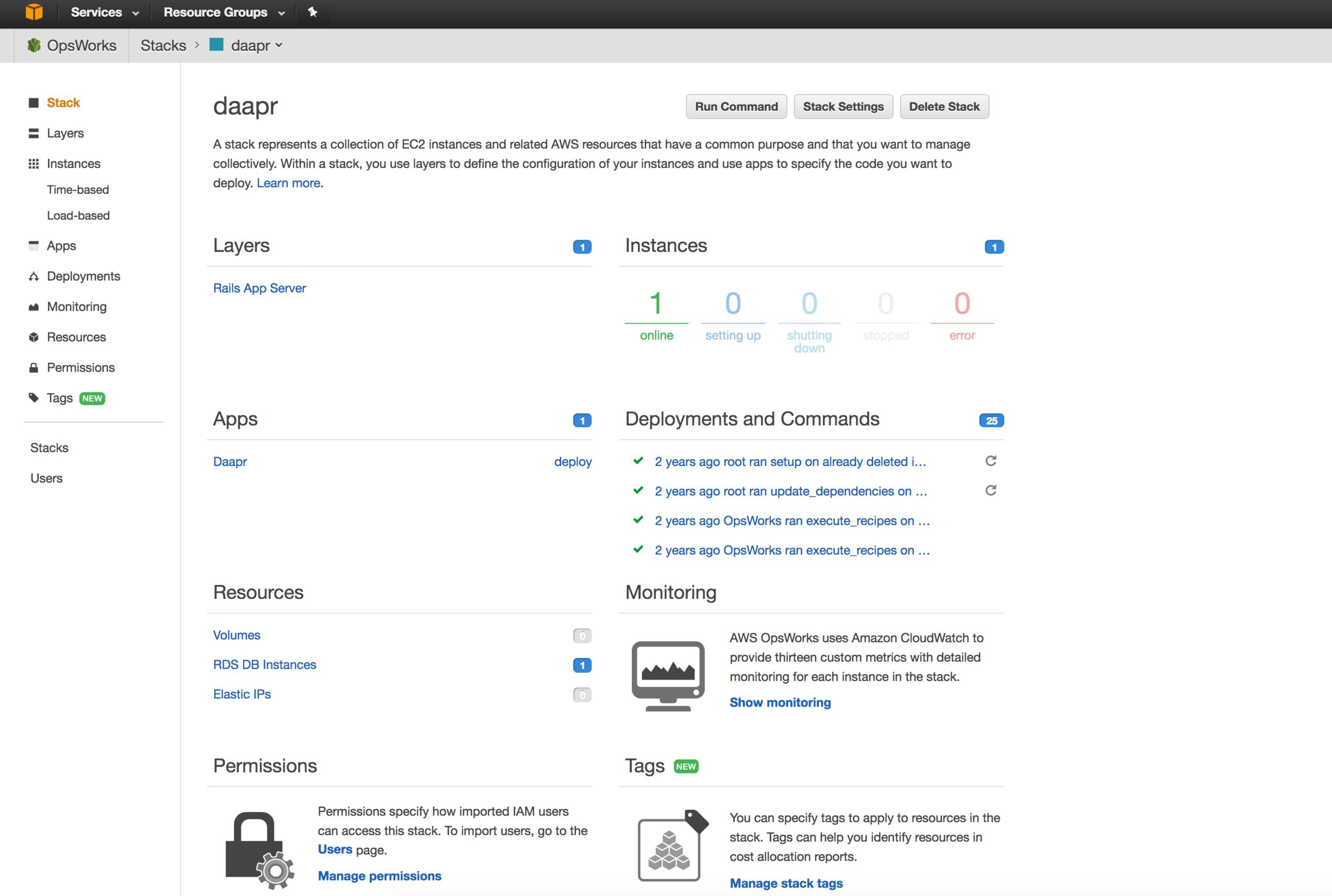

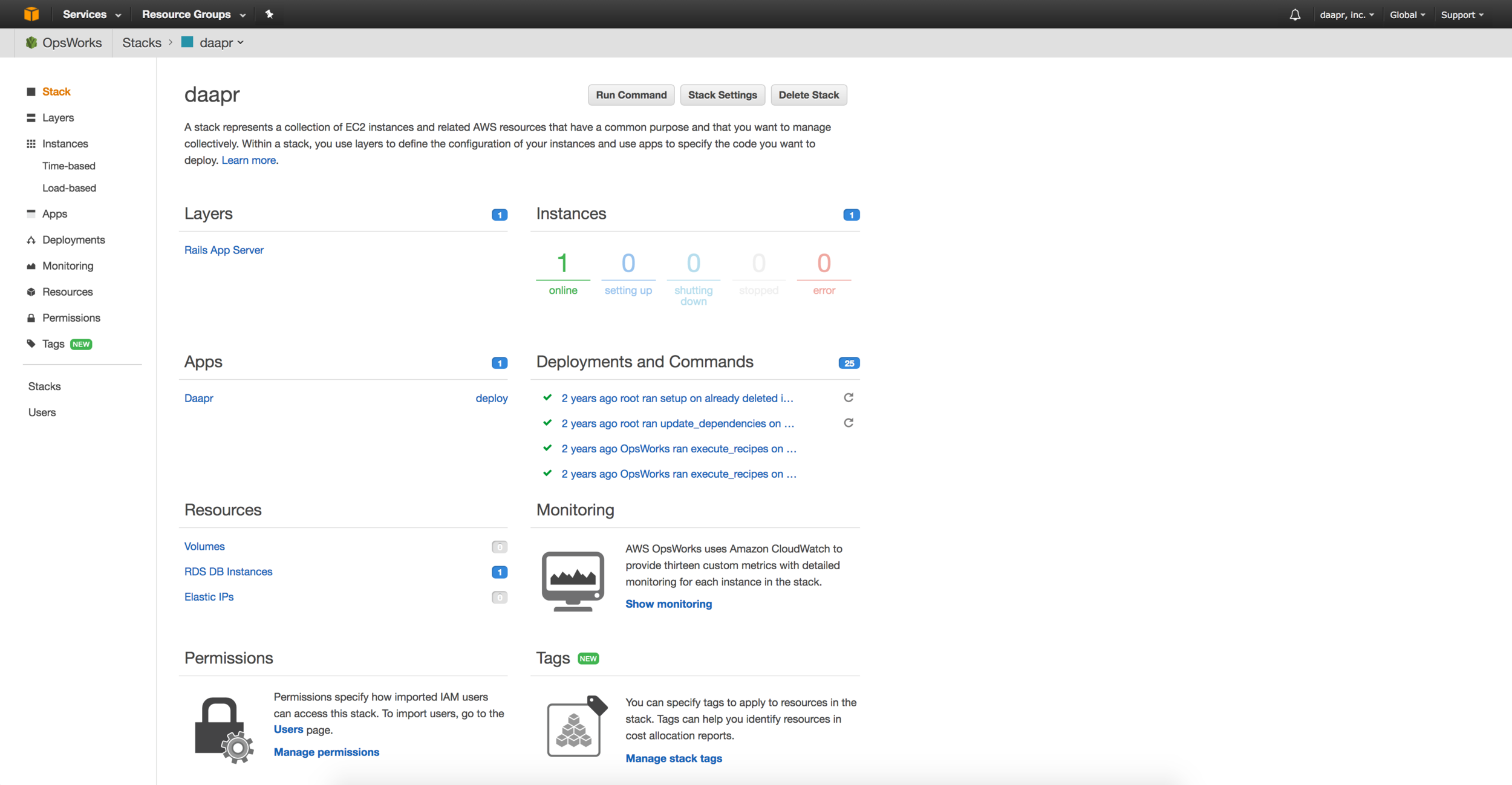

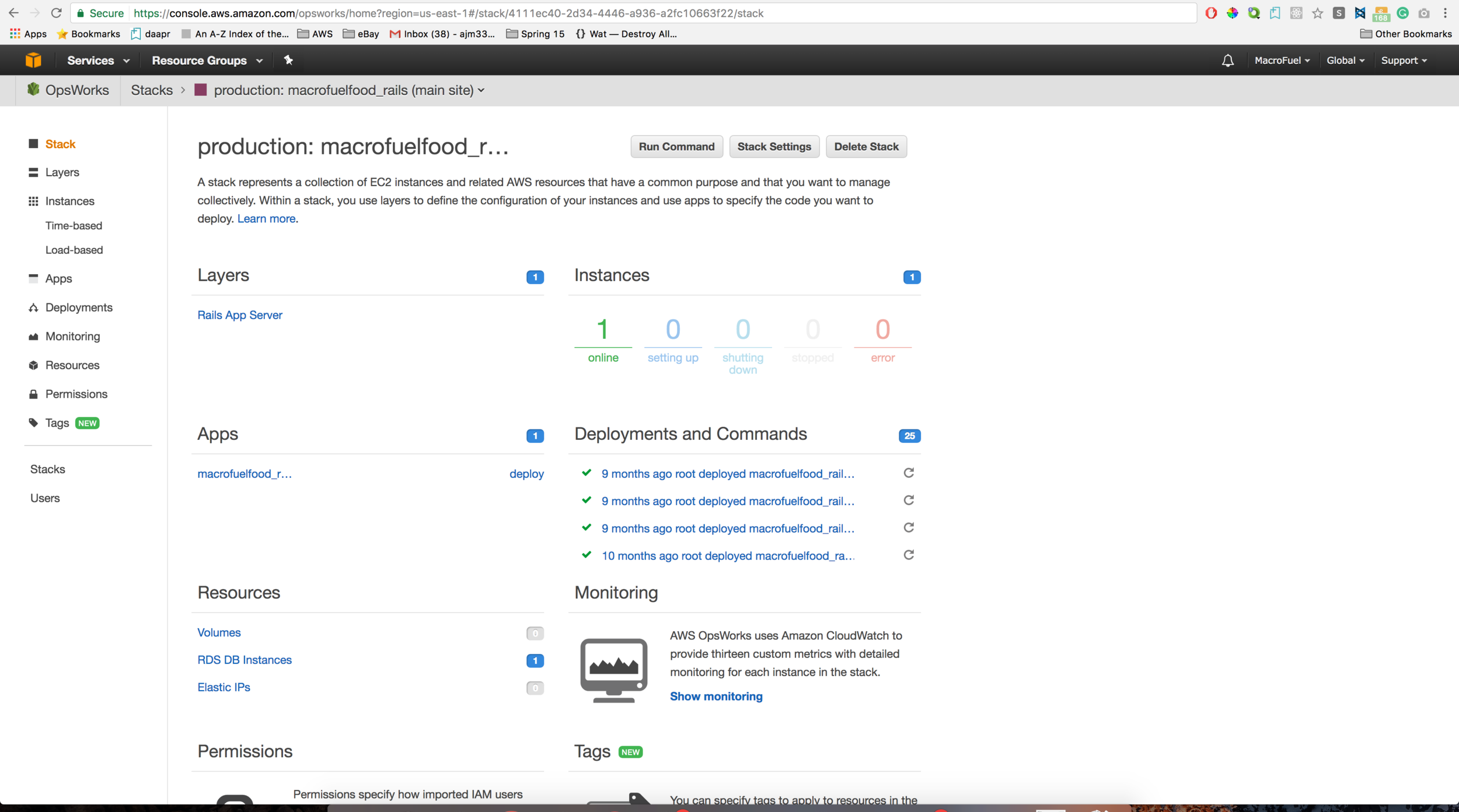

I was the sole designer and developer on MacroFuel (I did the primary design work with input from Gus on some user interface tweaks). The infrastructure for MacroFuel built upon my learnings from daapr. I started with Amazon Web Services (AWS) from the start to avoid potential scaling issues and because we had free AWS credits. I also used Compose for our database to avoid having to worry about backups and scaling, and our domain name was through Namecheap.

Company Website and Company Blog

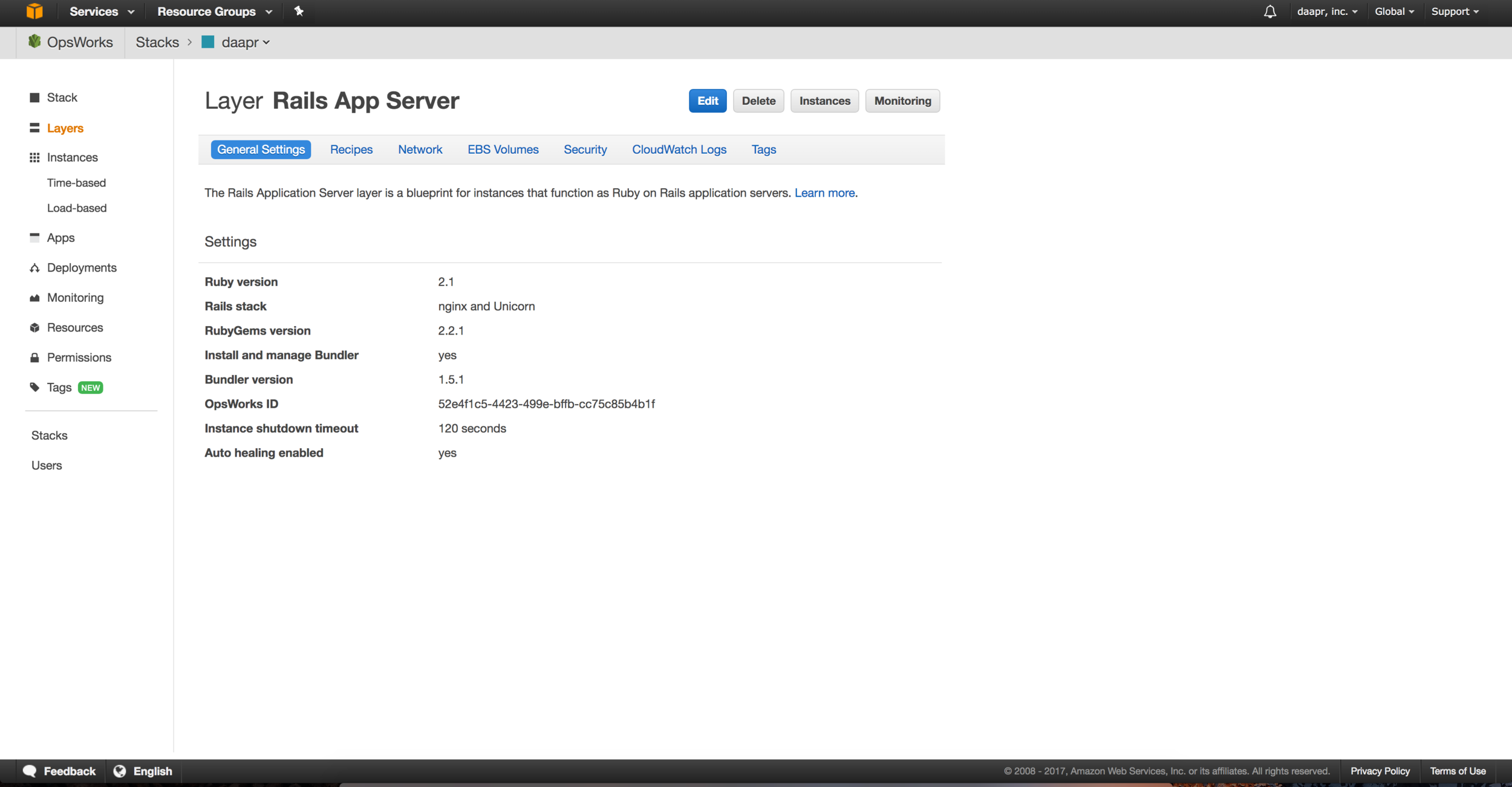

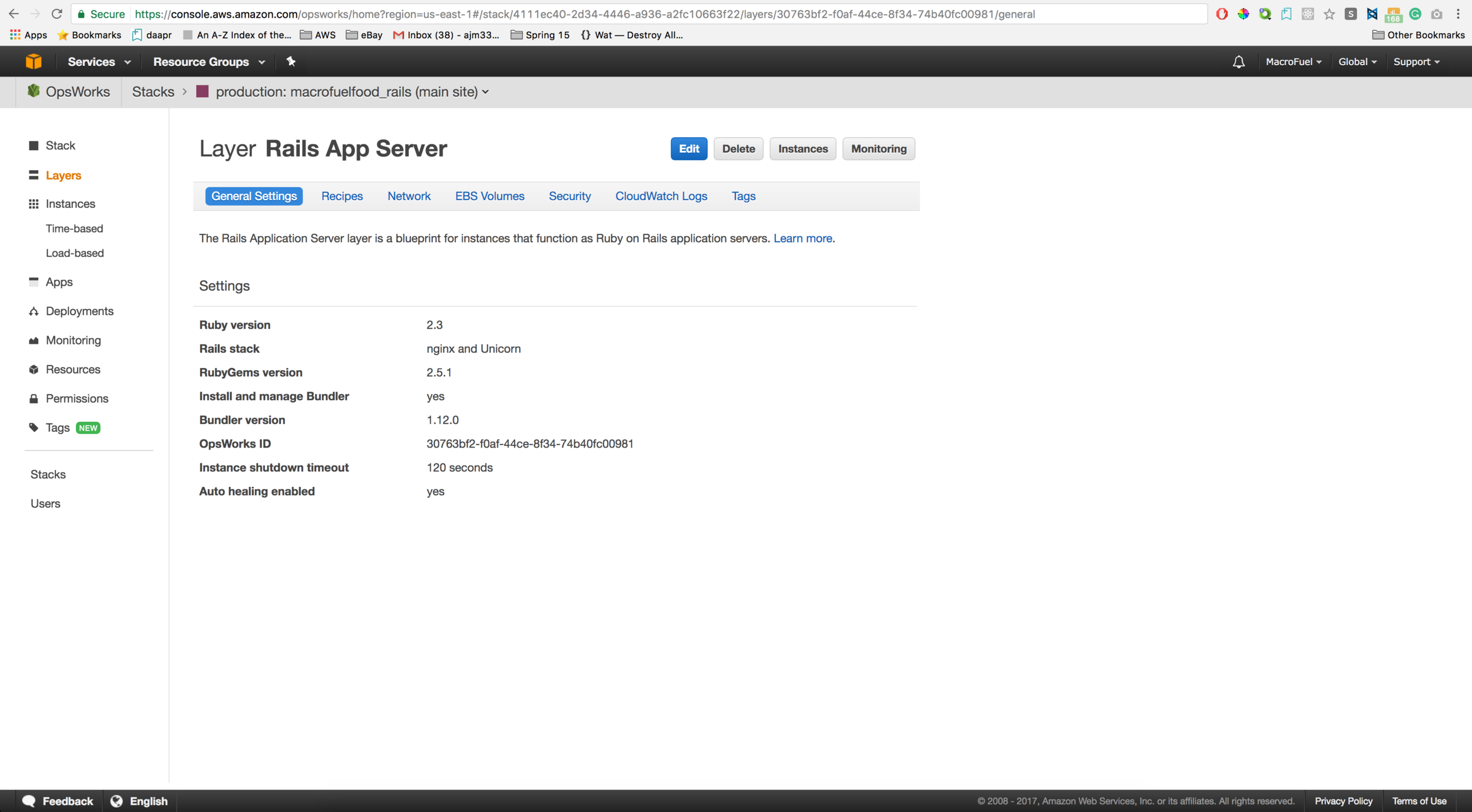

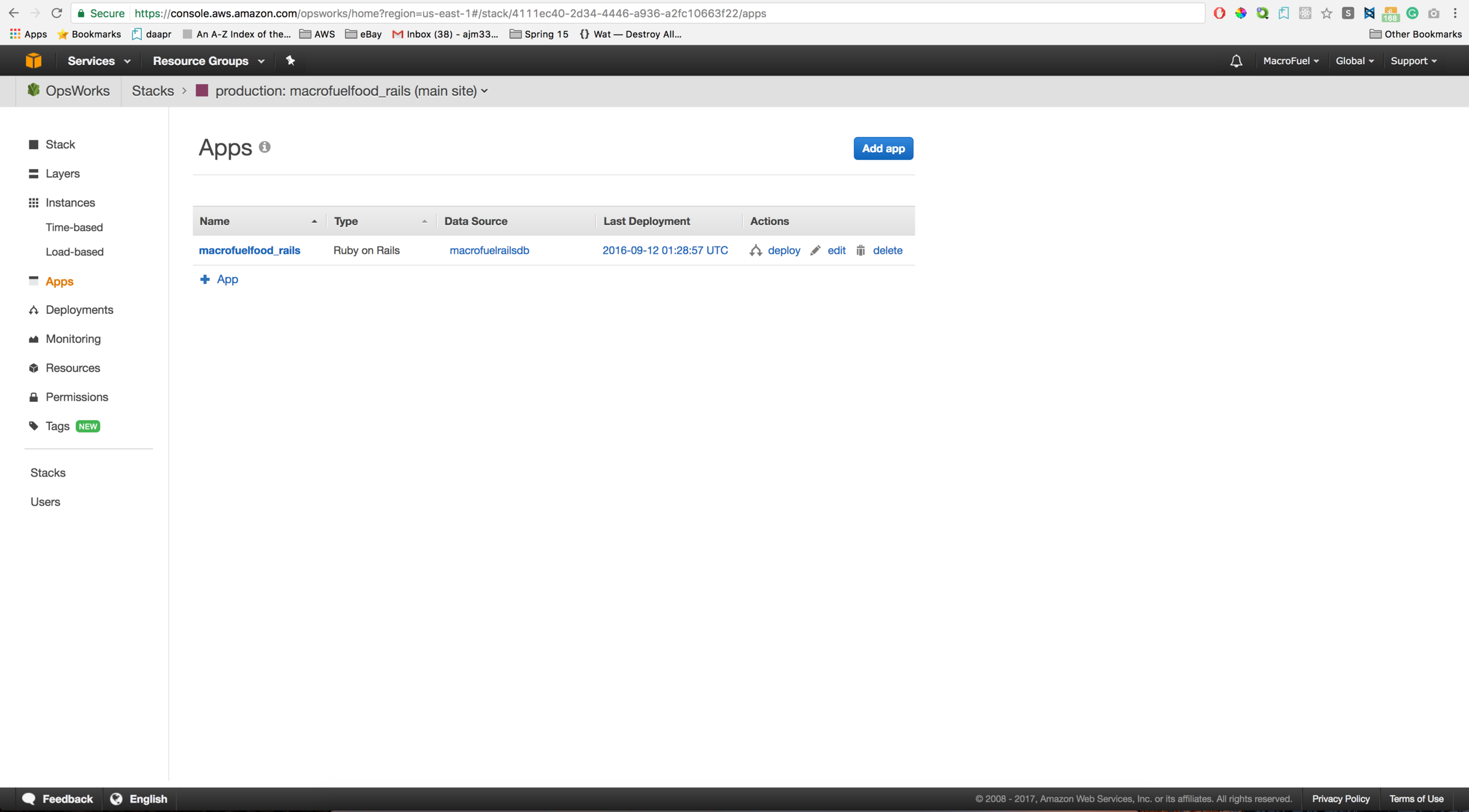

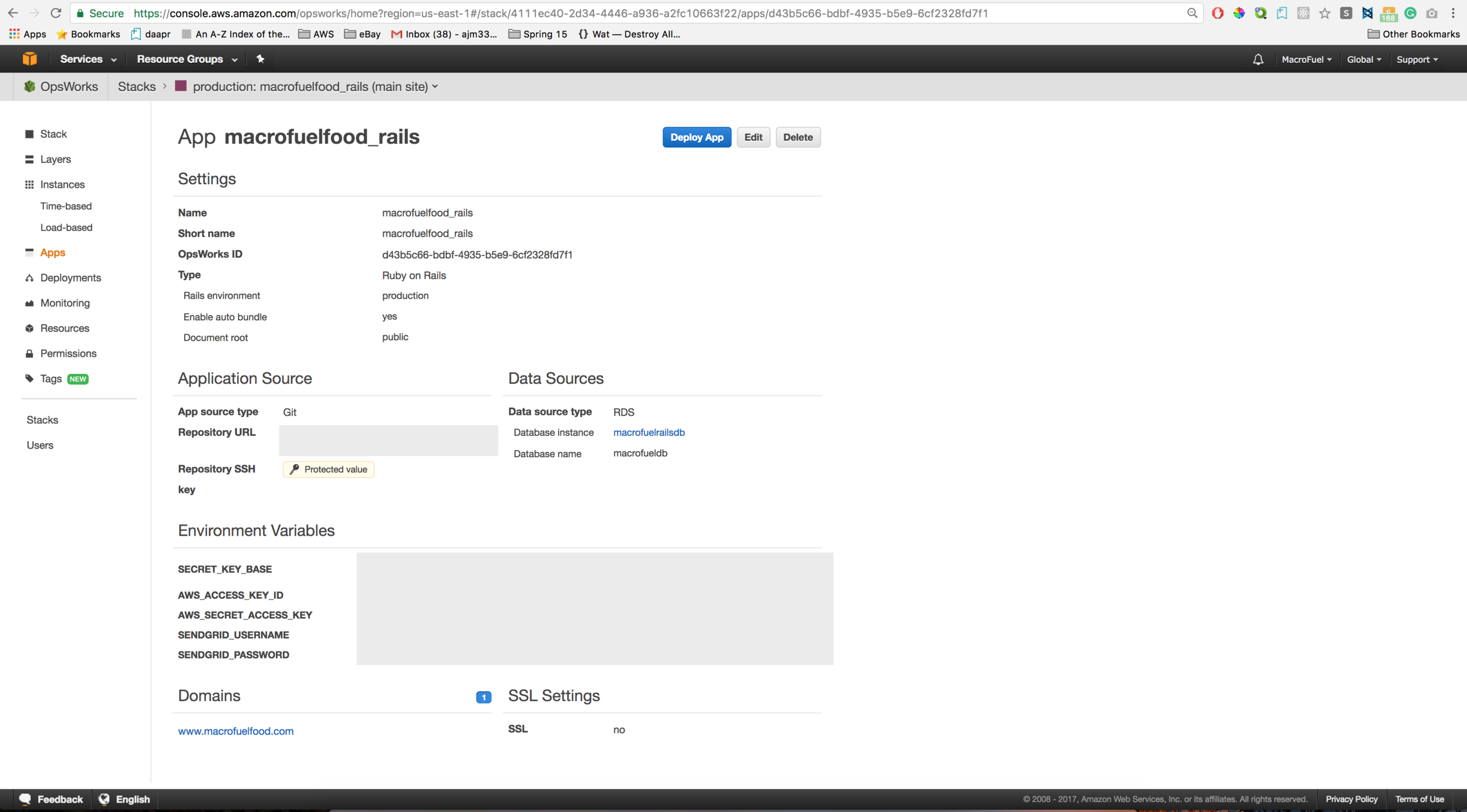

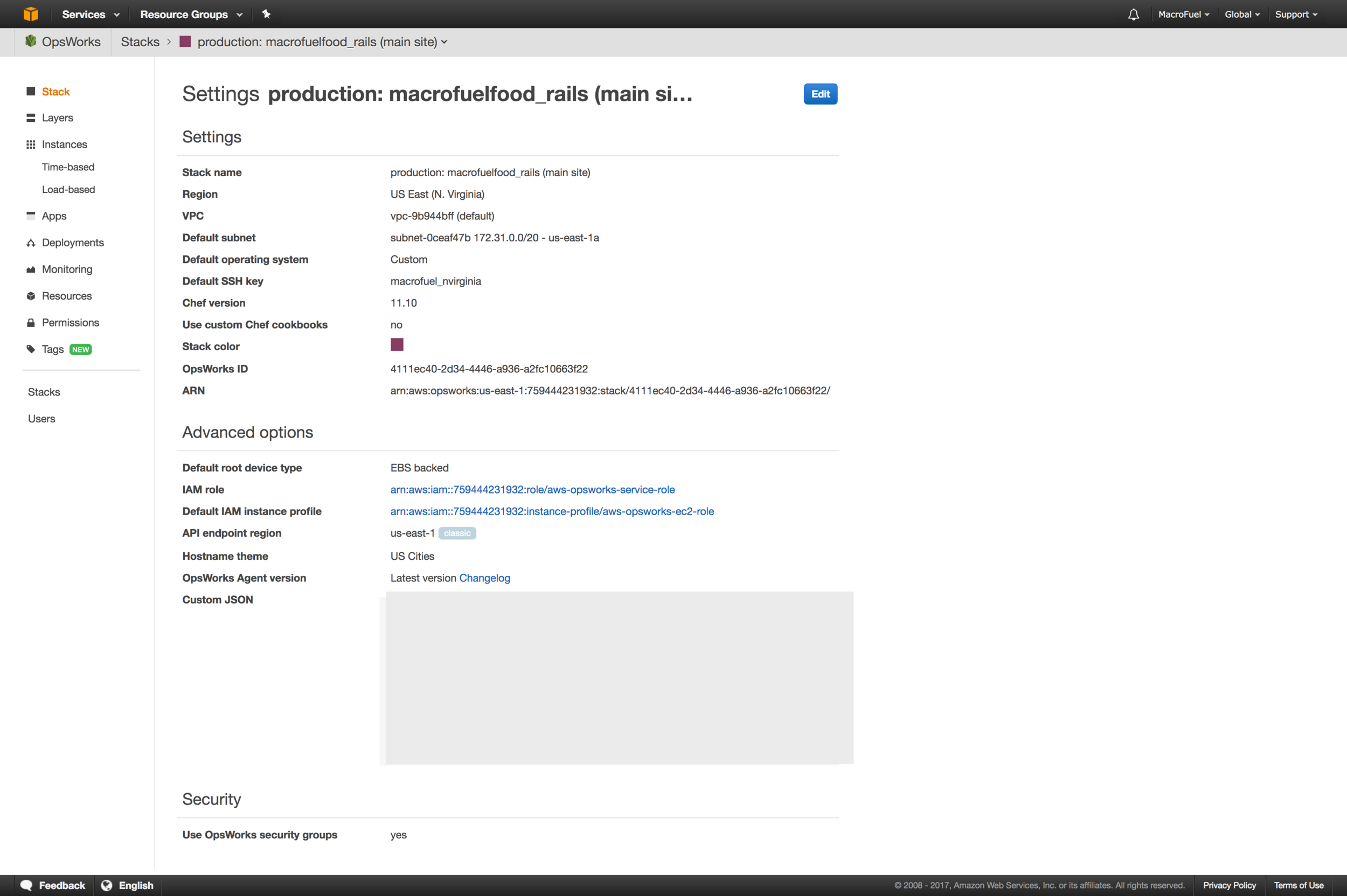

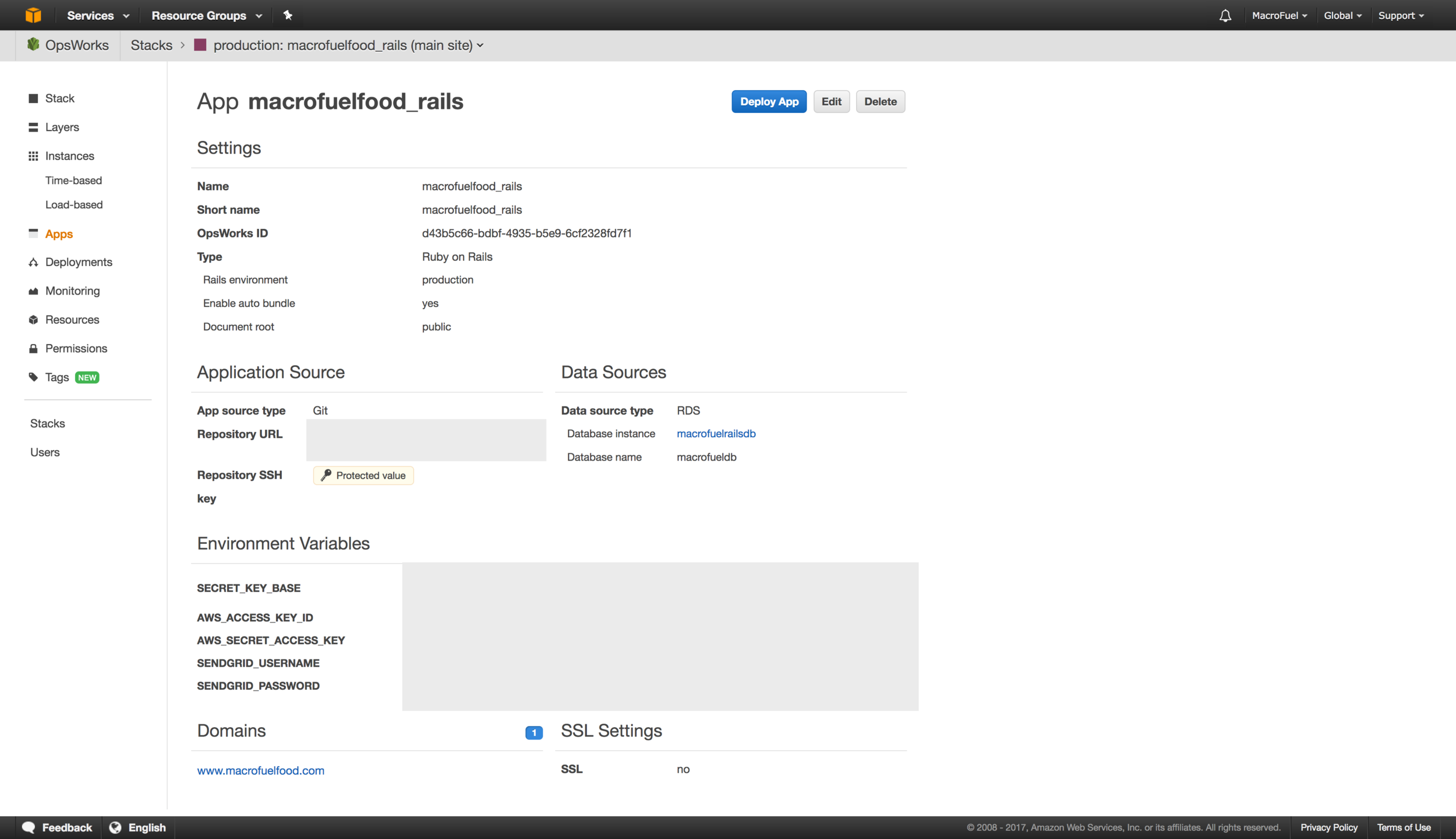

The Company Website and Company Blog were written in Ruby on Rails in order to utilize server-side rendering necessary for Google to crawl the site. The technologies that I used for the other applications were not SEO-friendly because they were all JavaScript based and rendered on the client-side.

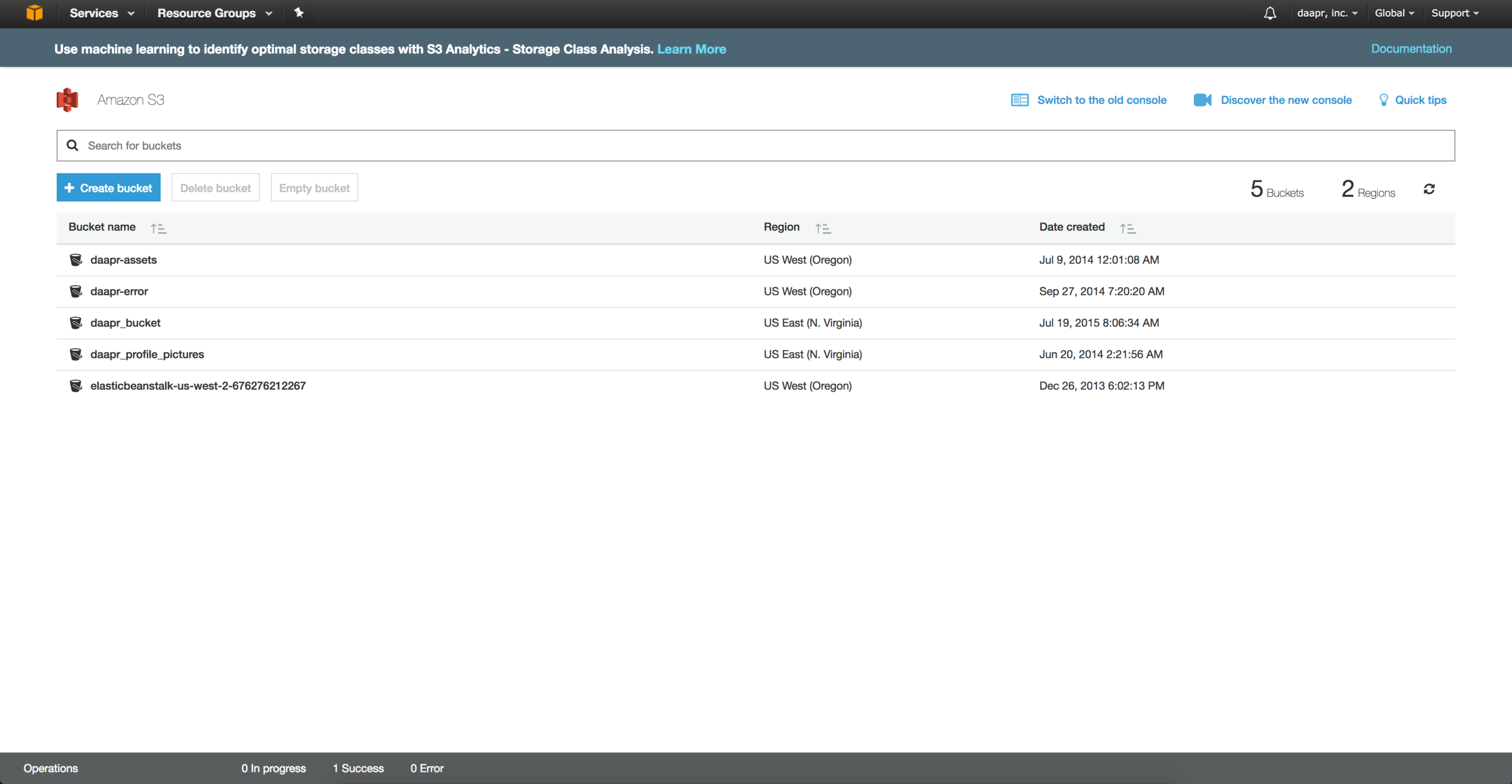

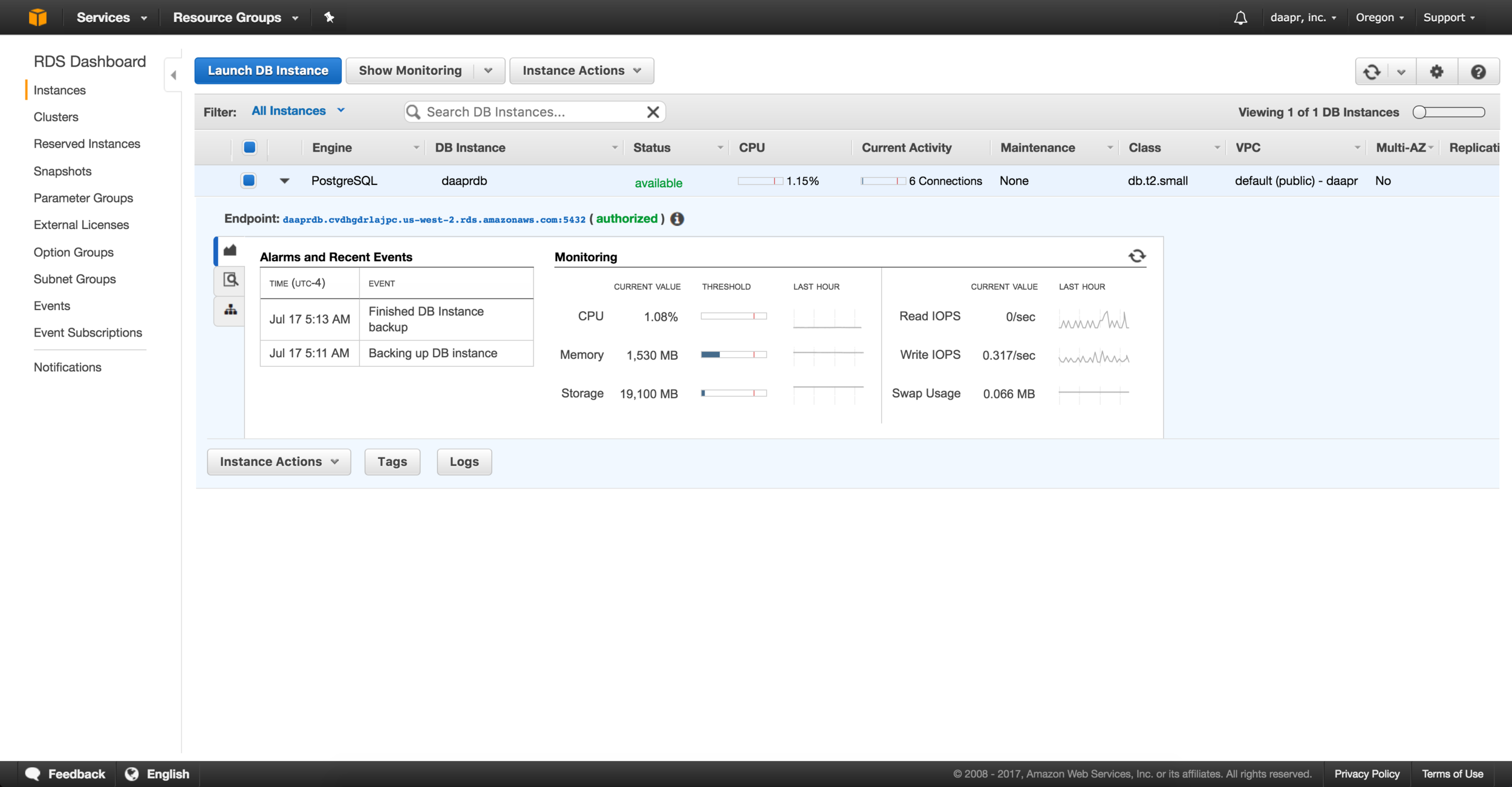

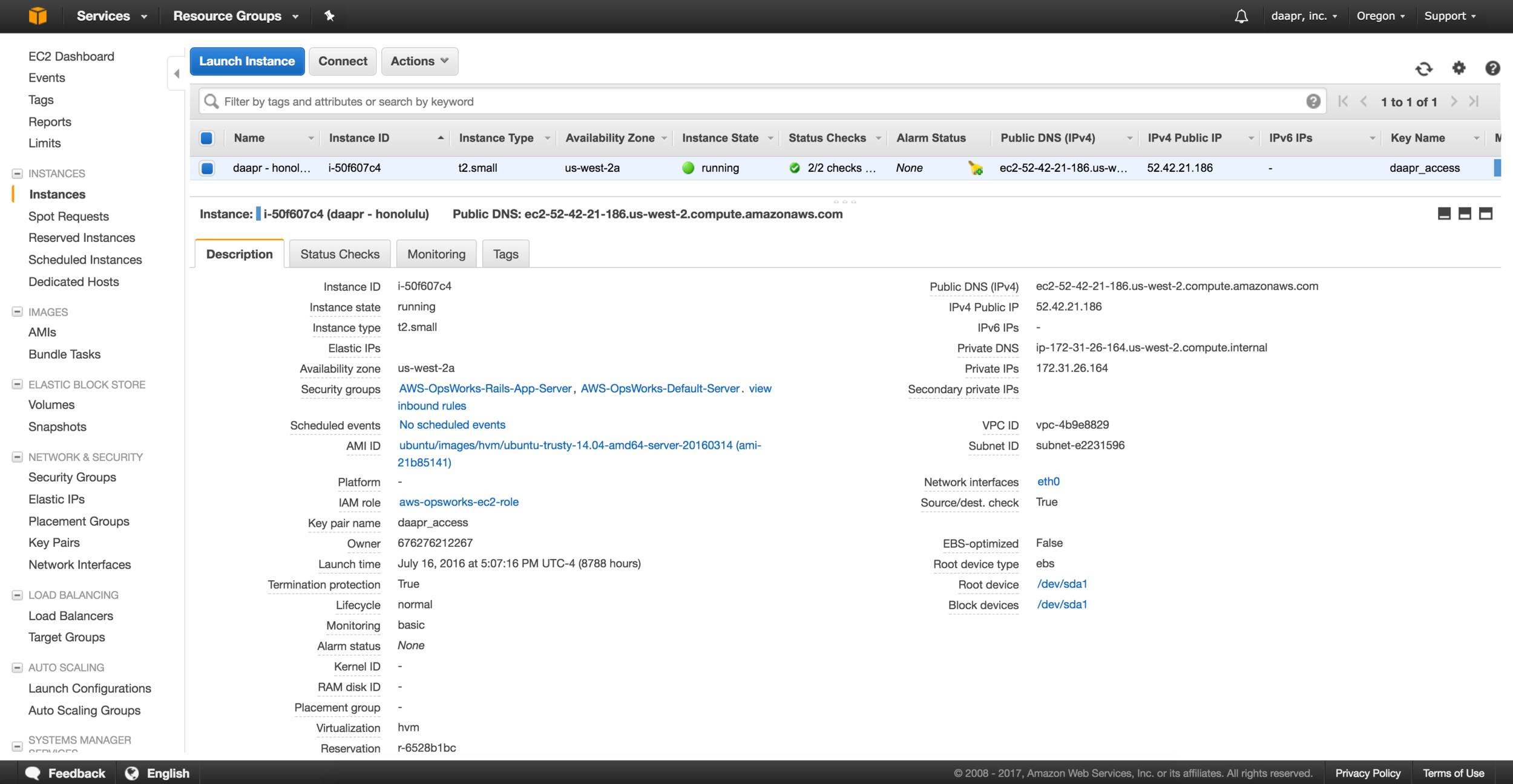

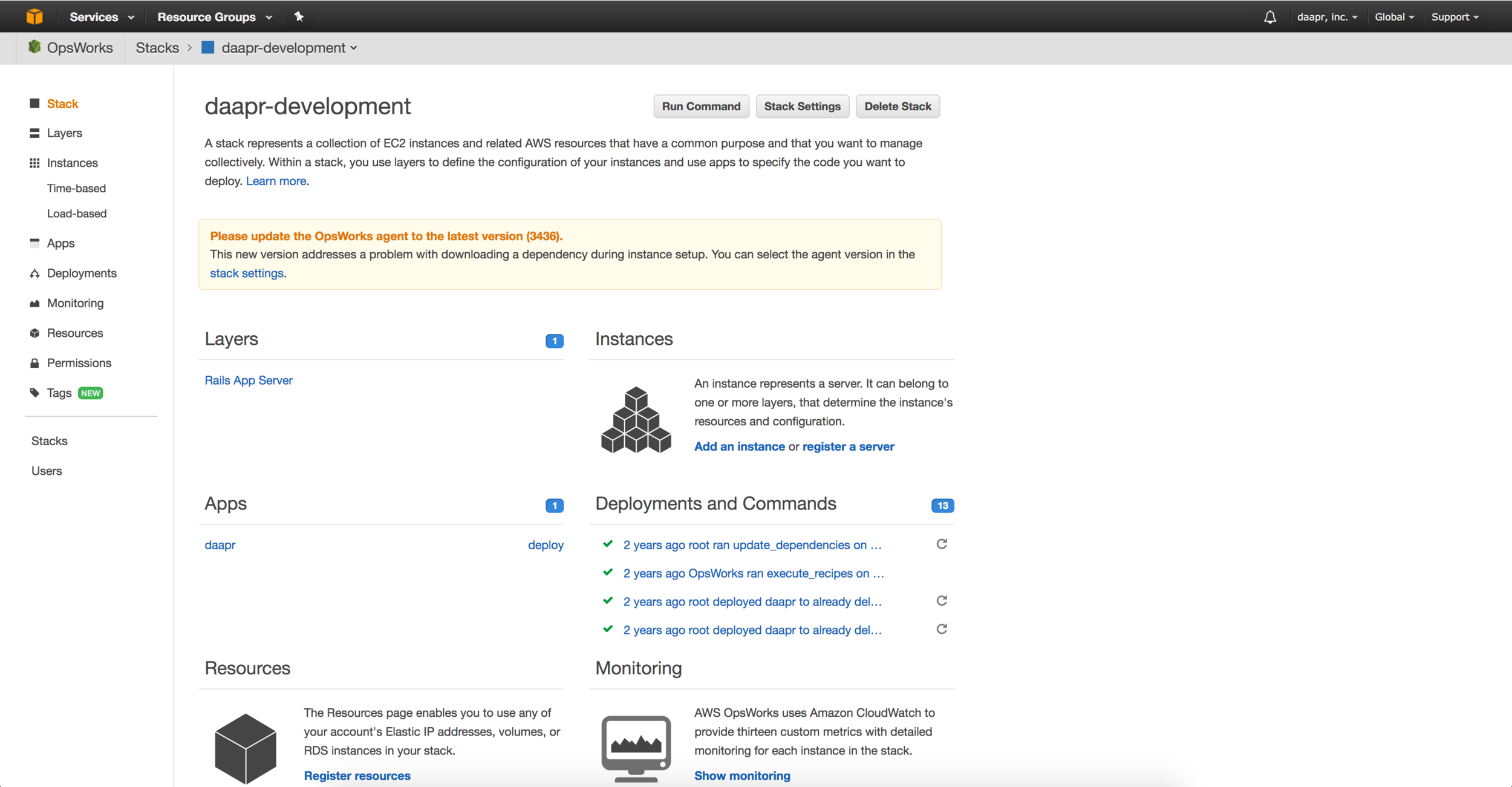

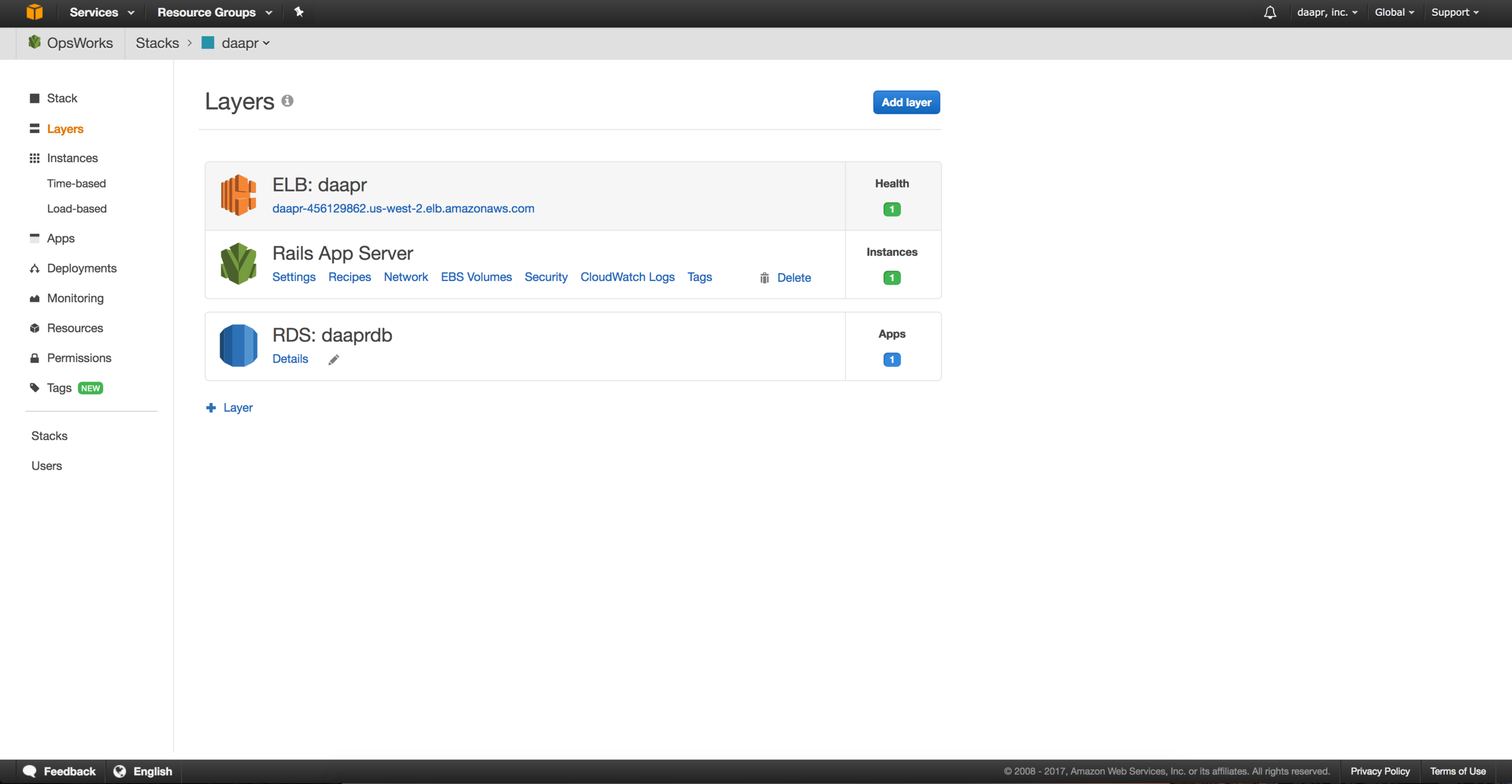

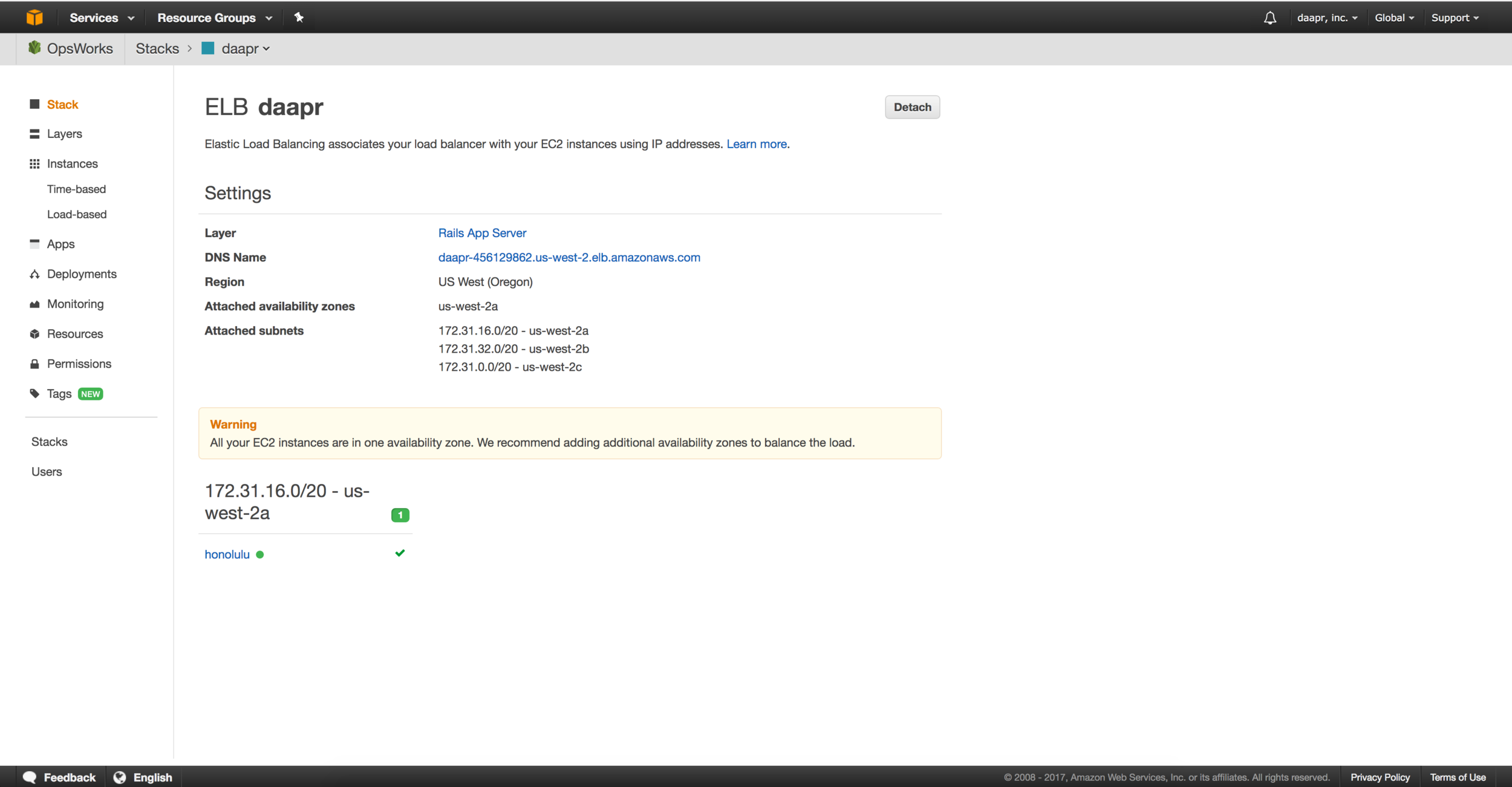

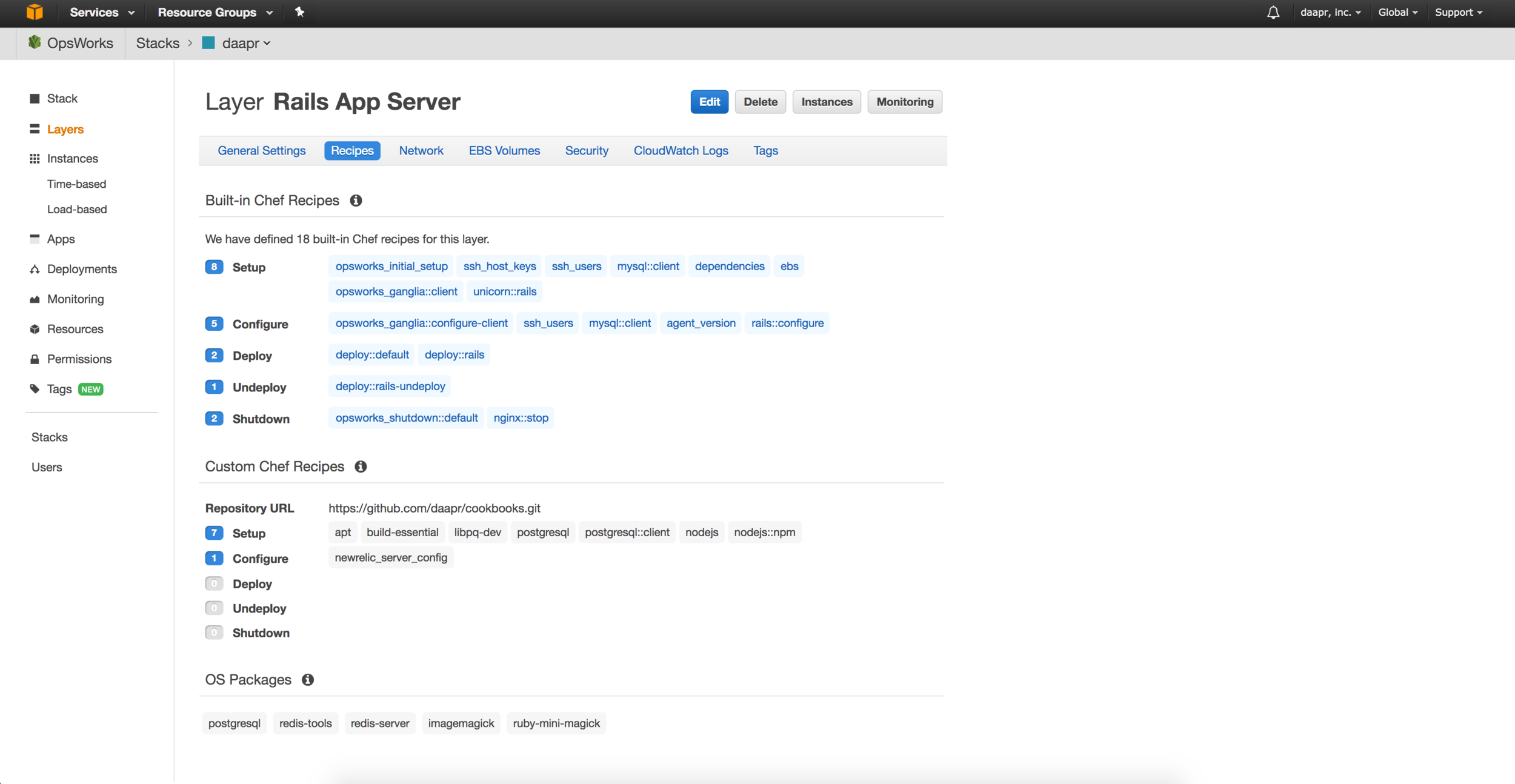

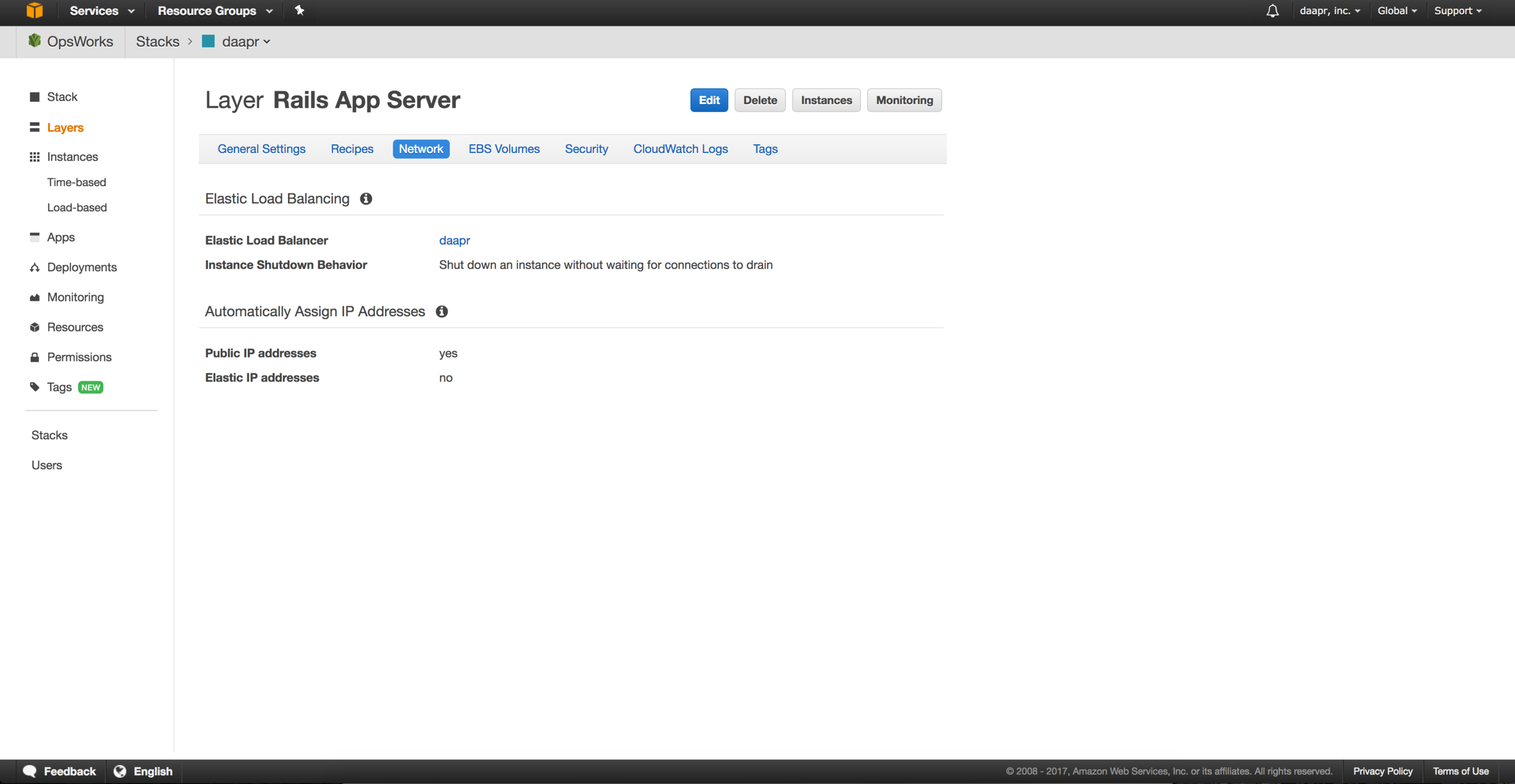

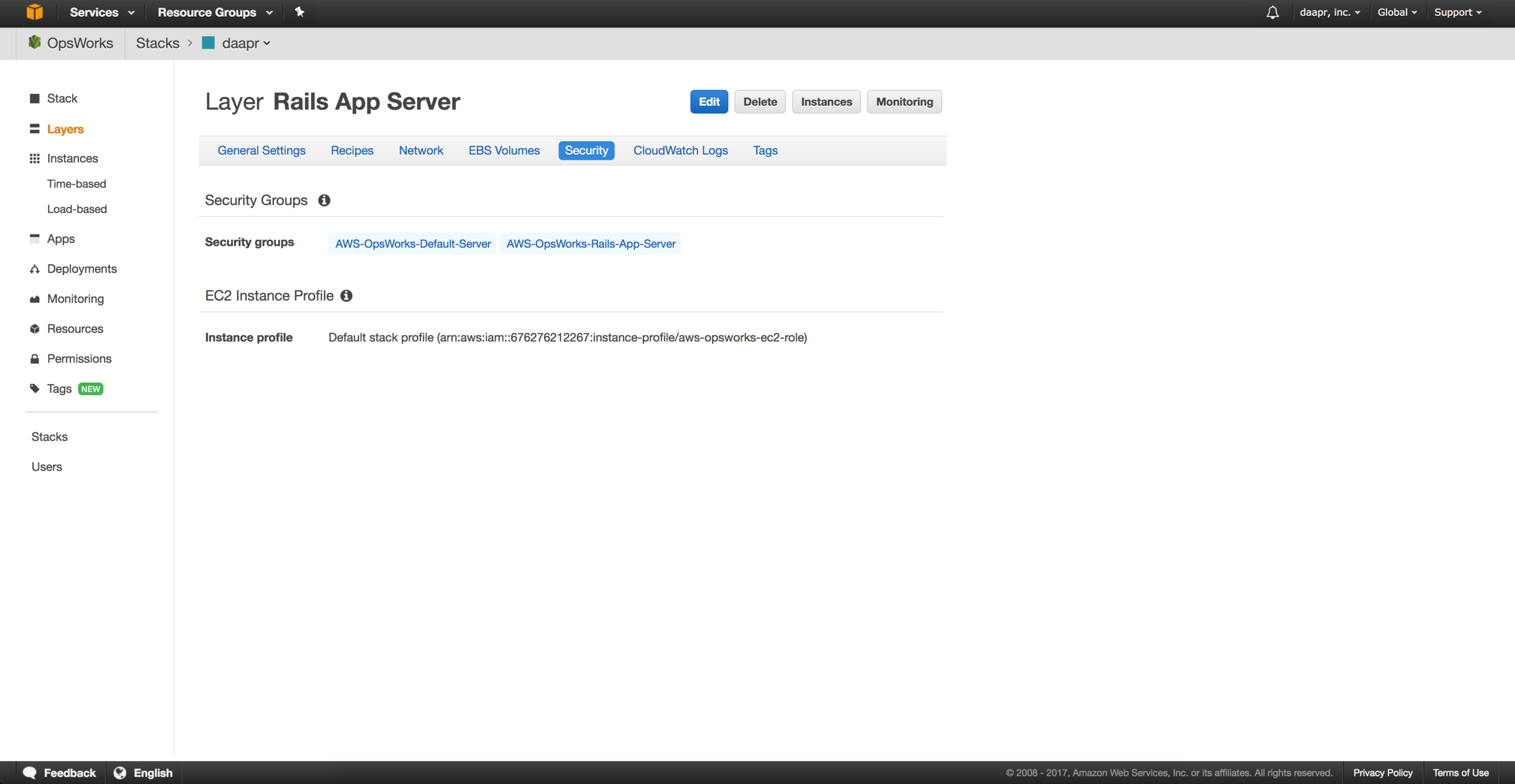

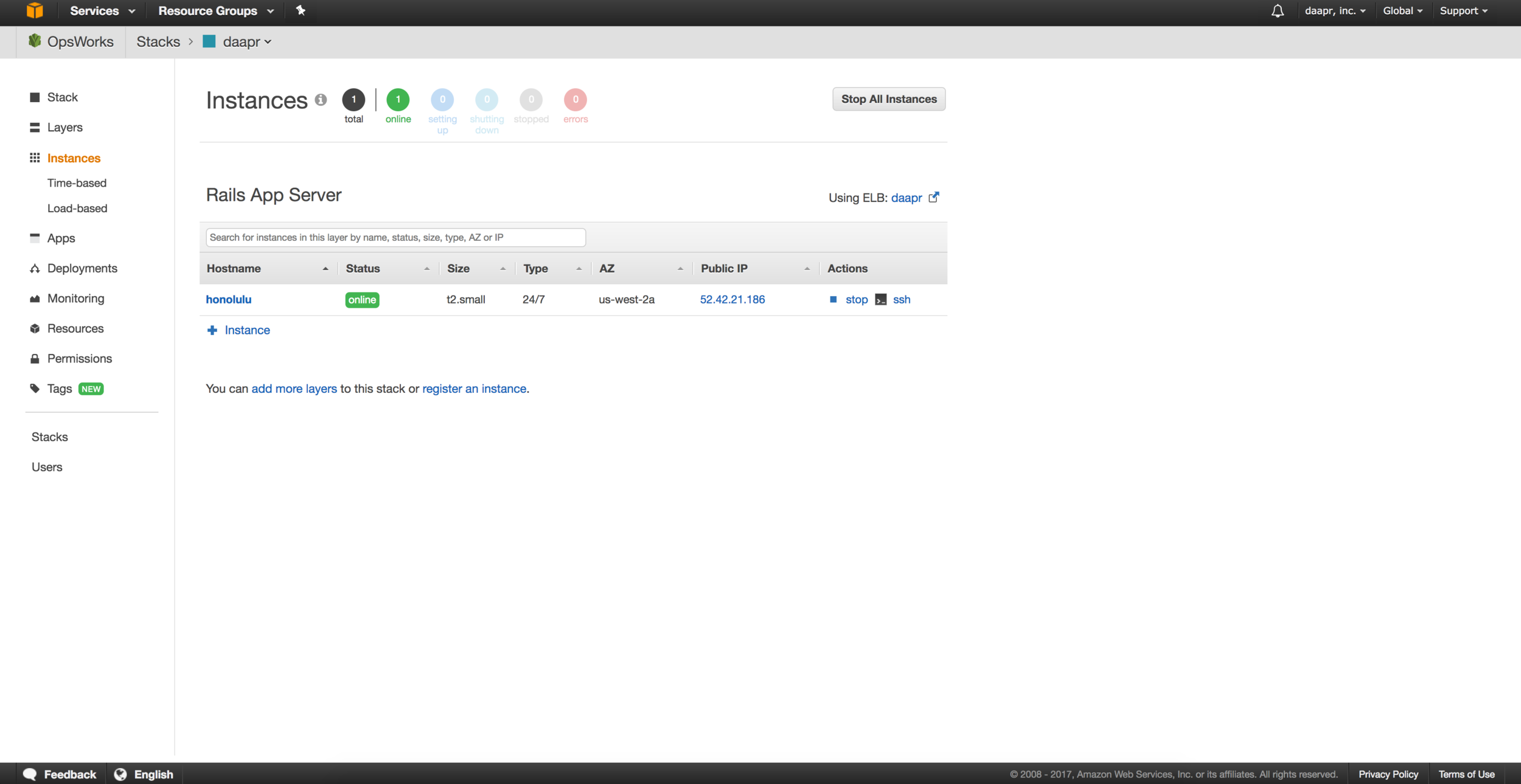

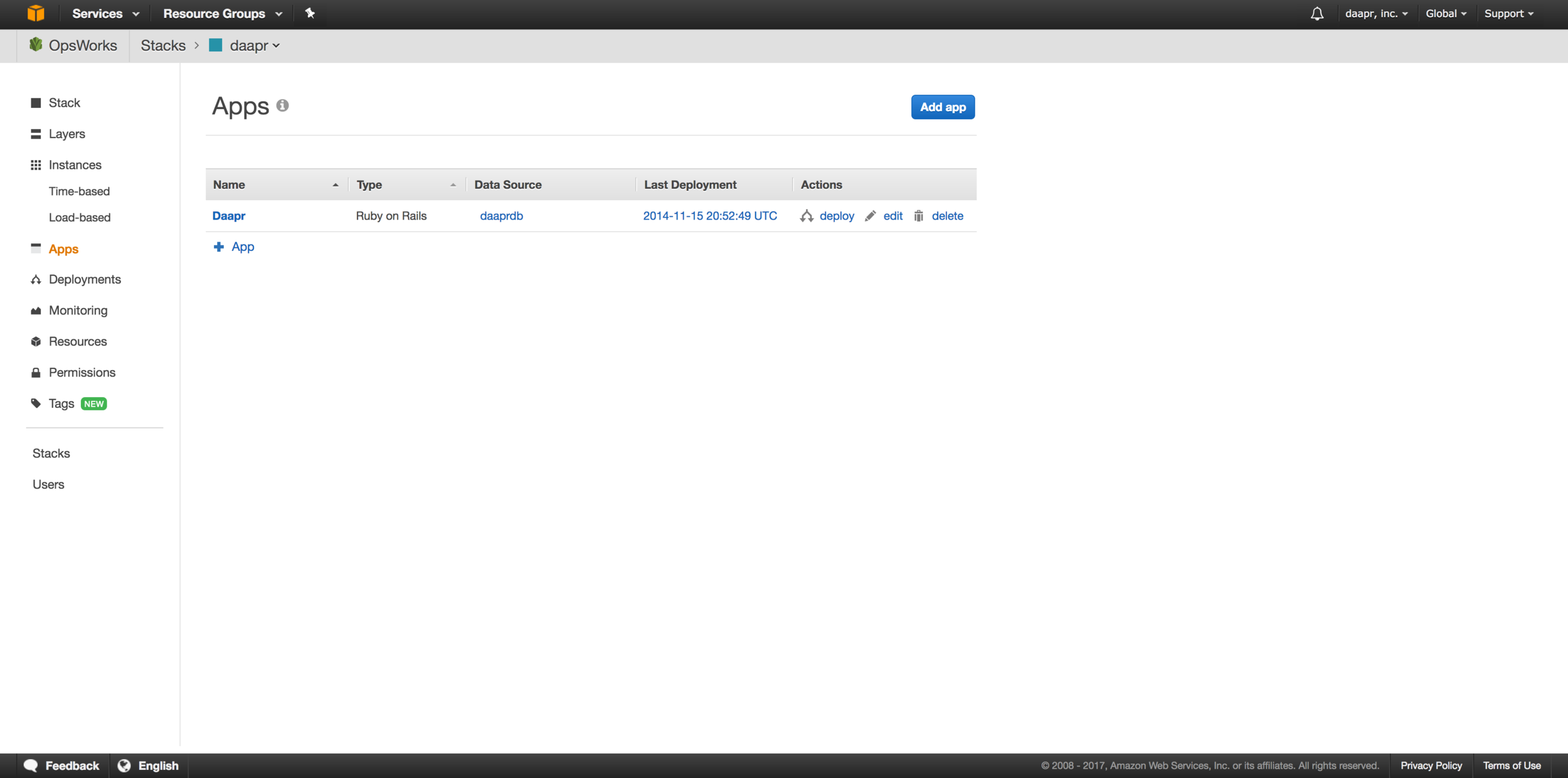

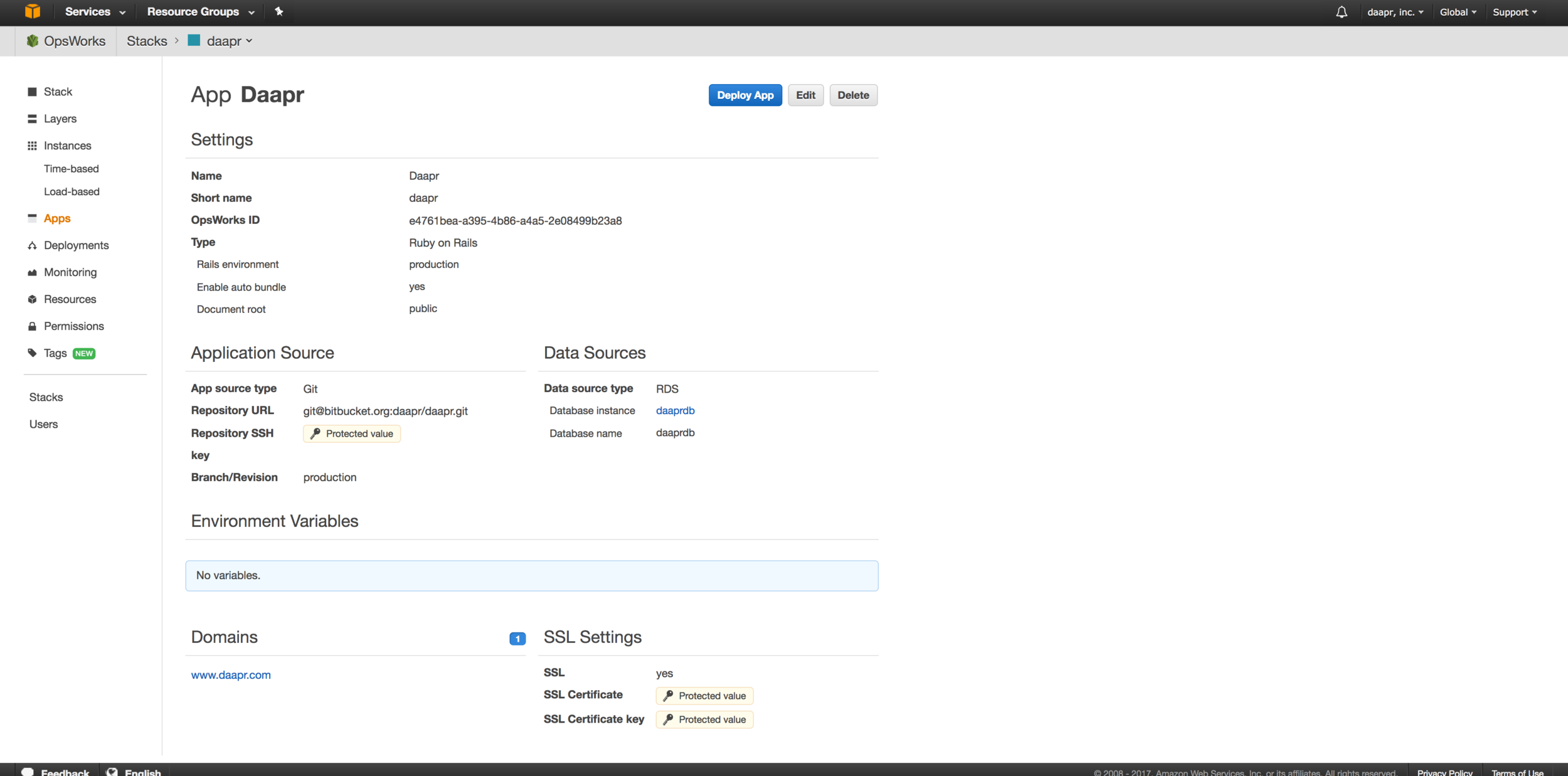

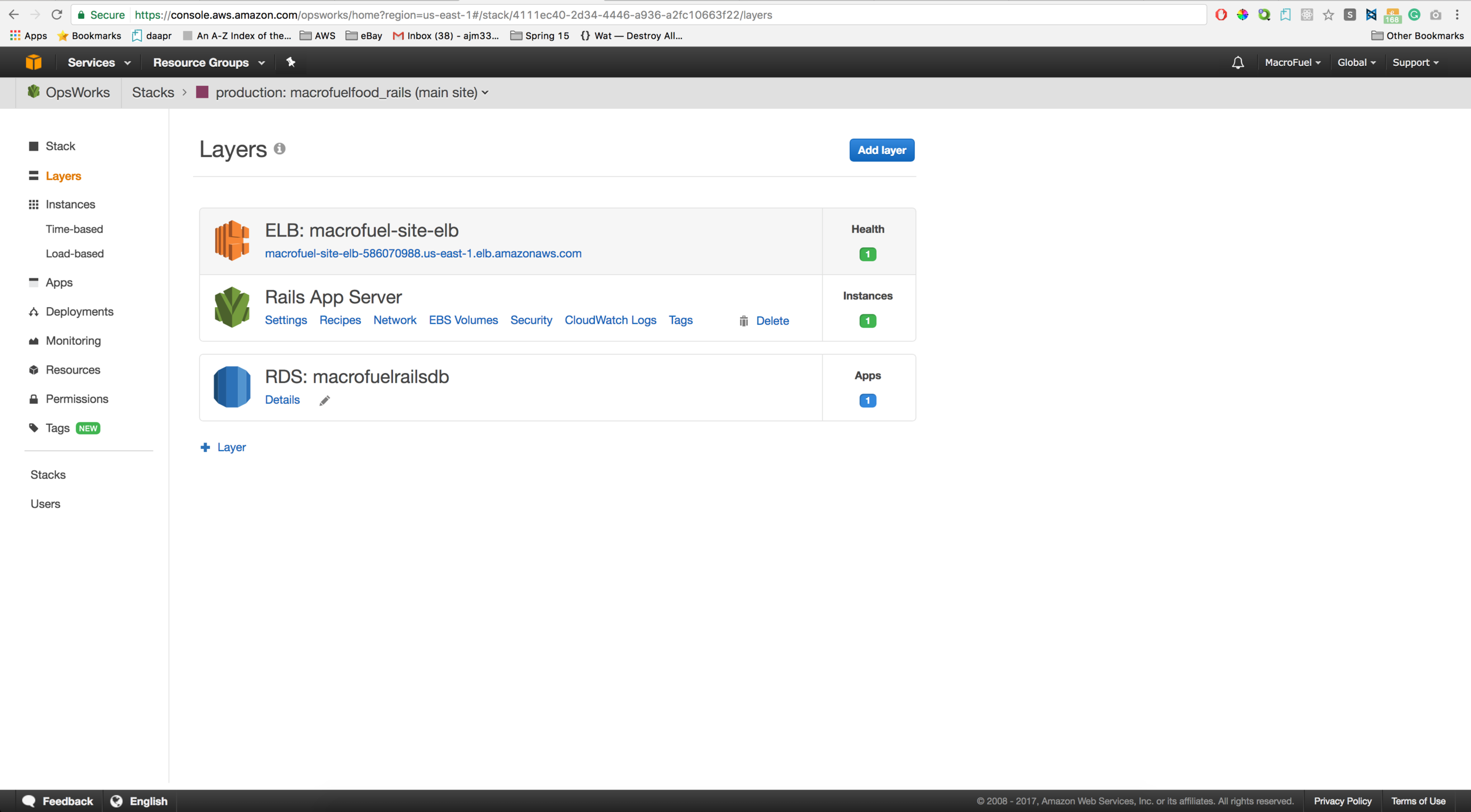

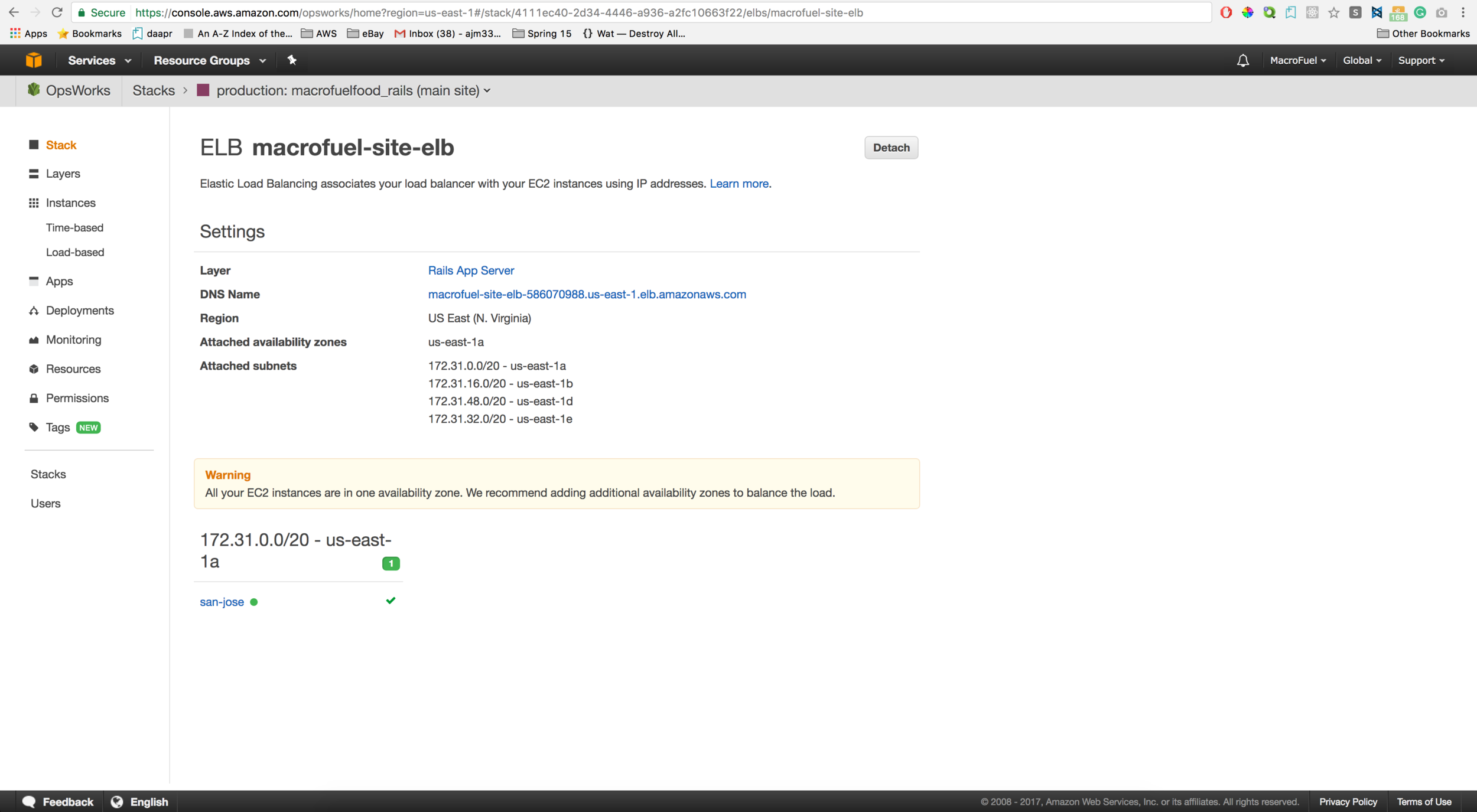

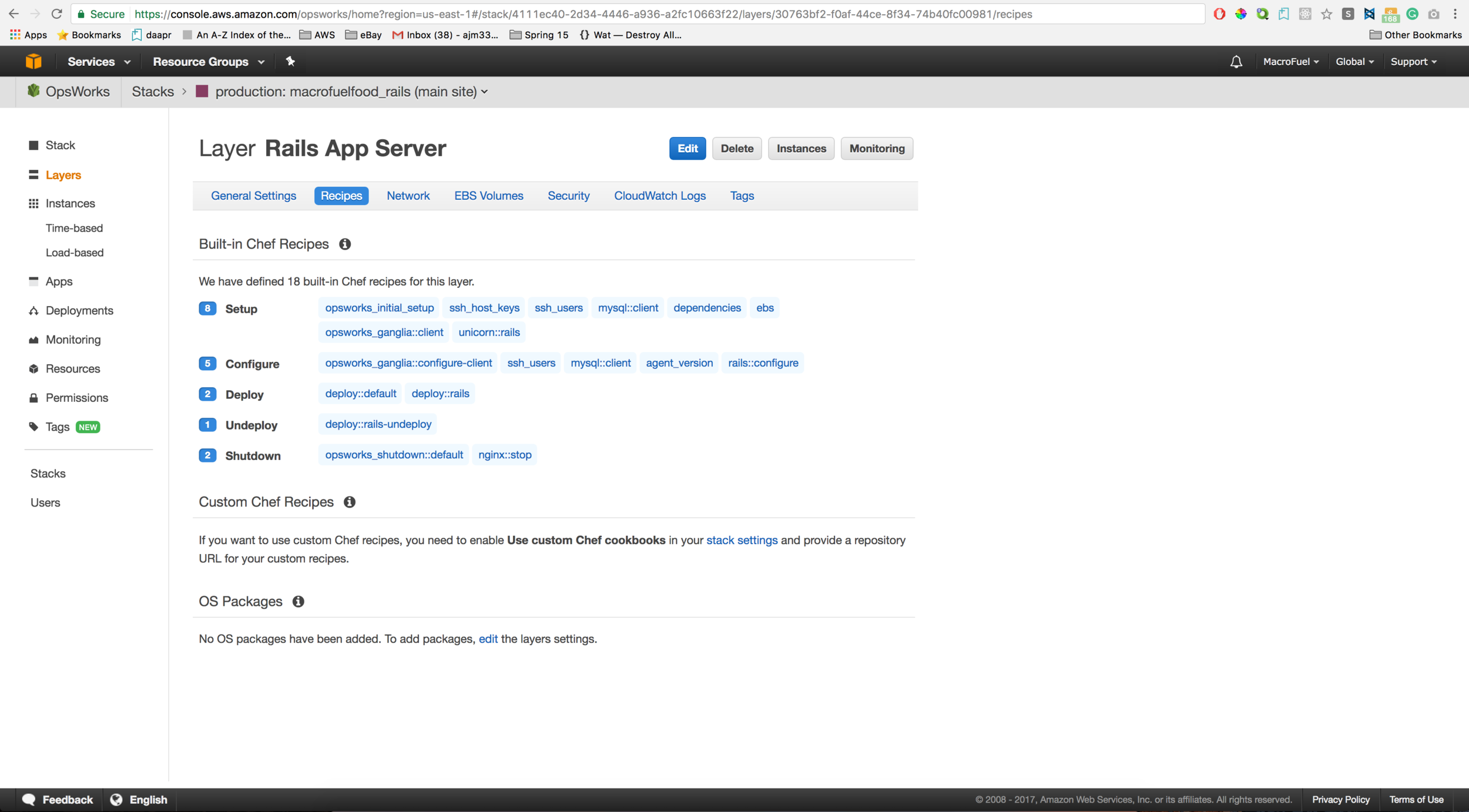

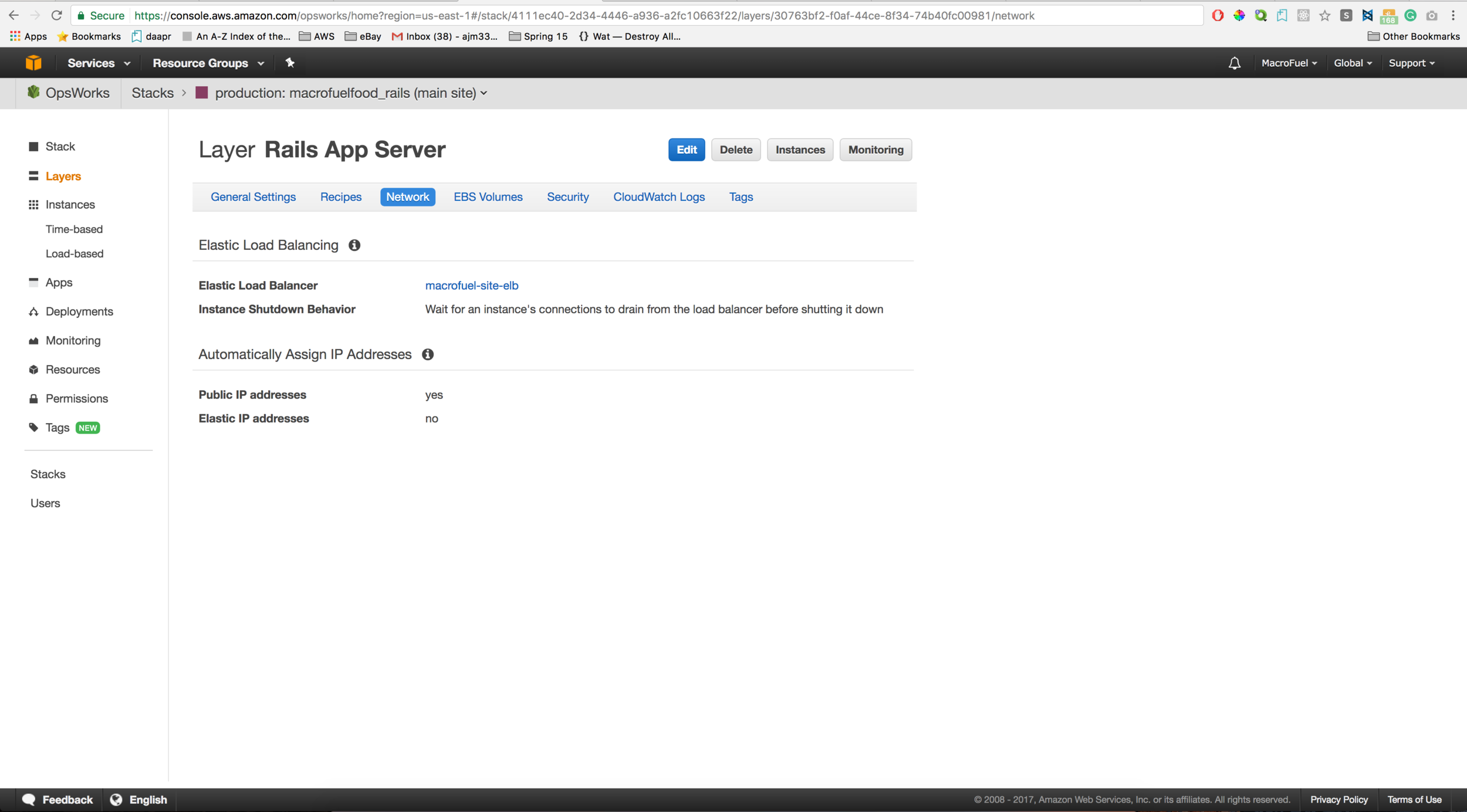

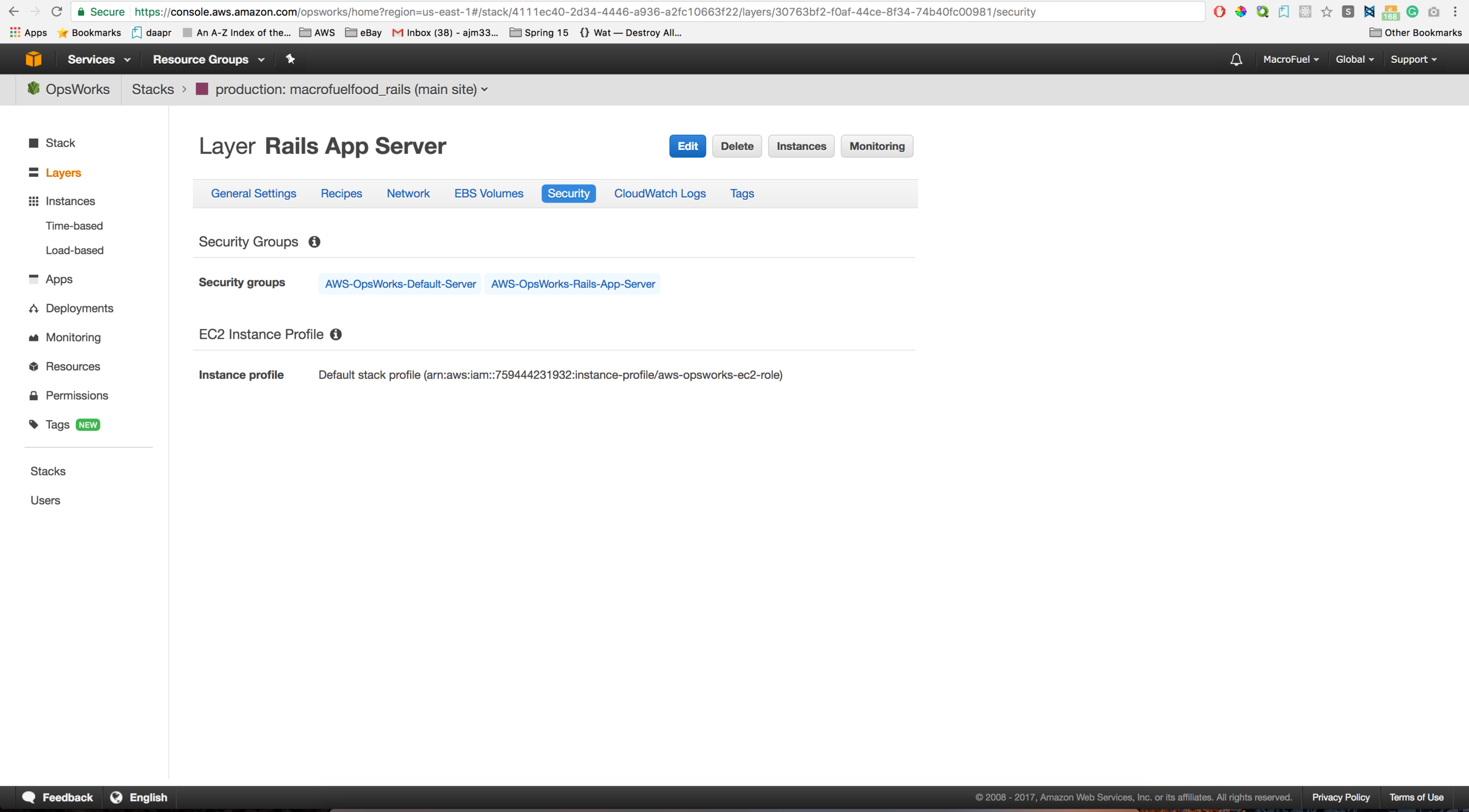

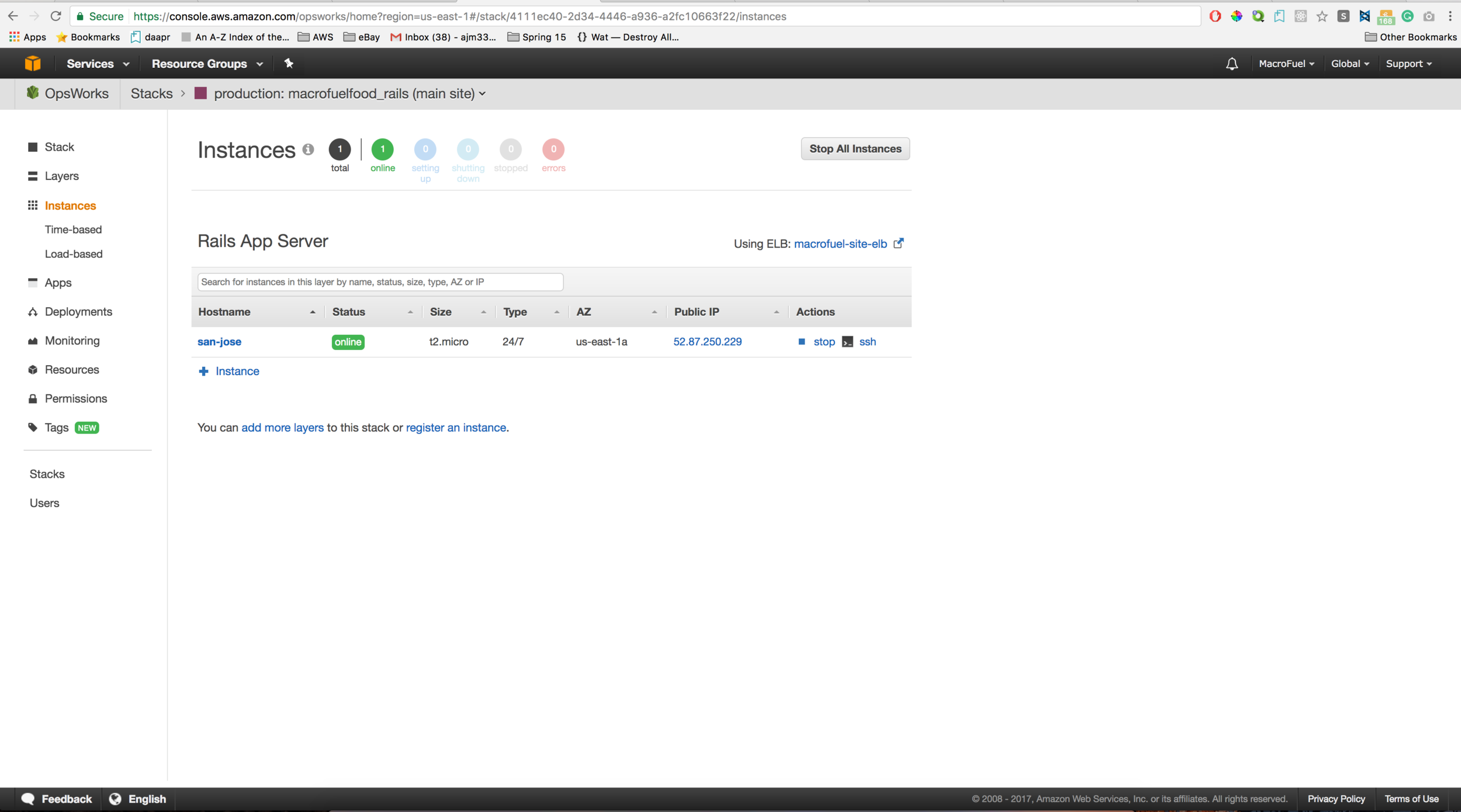

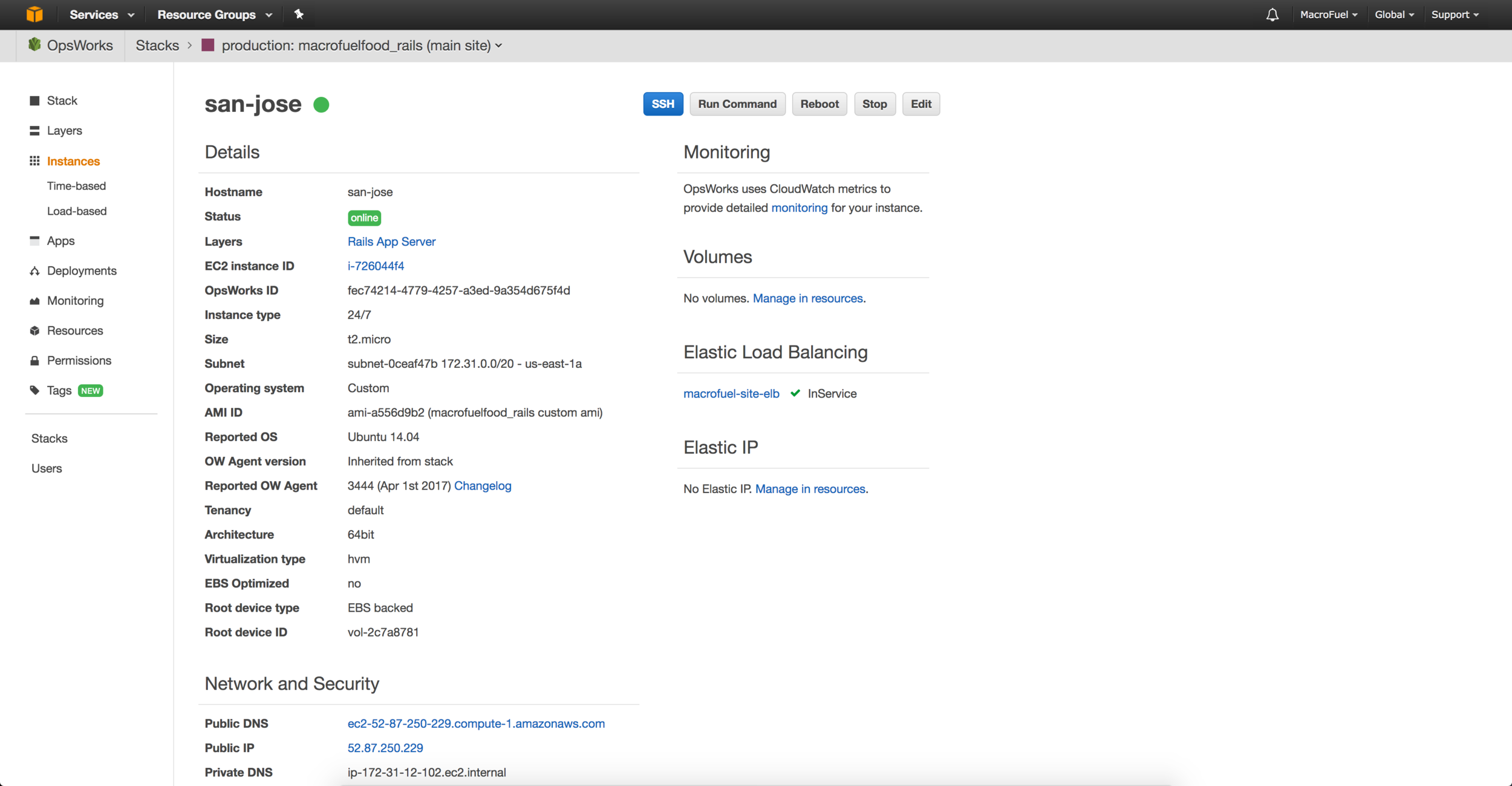

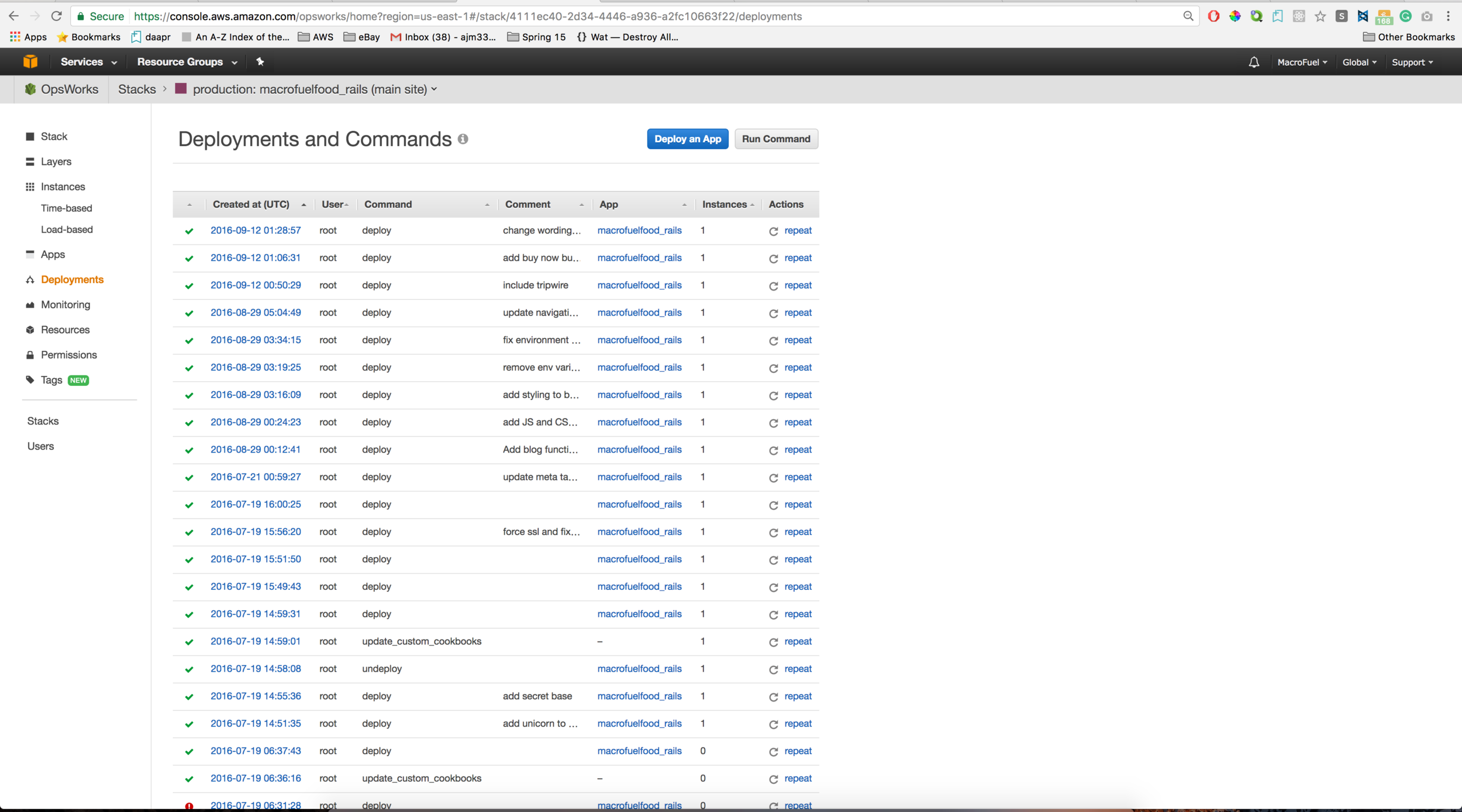

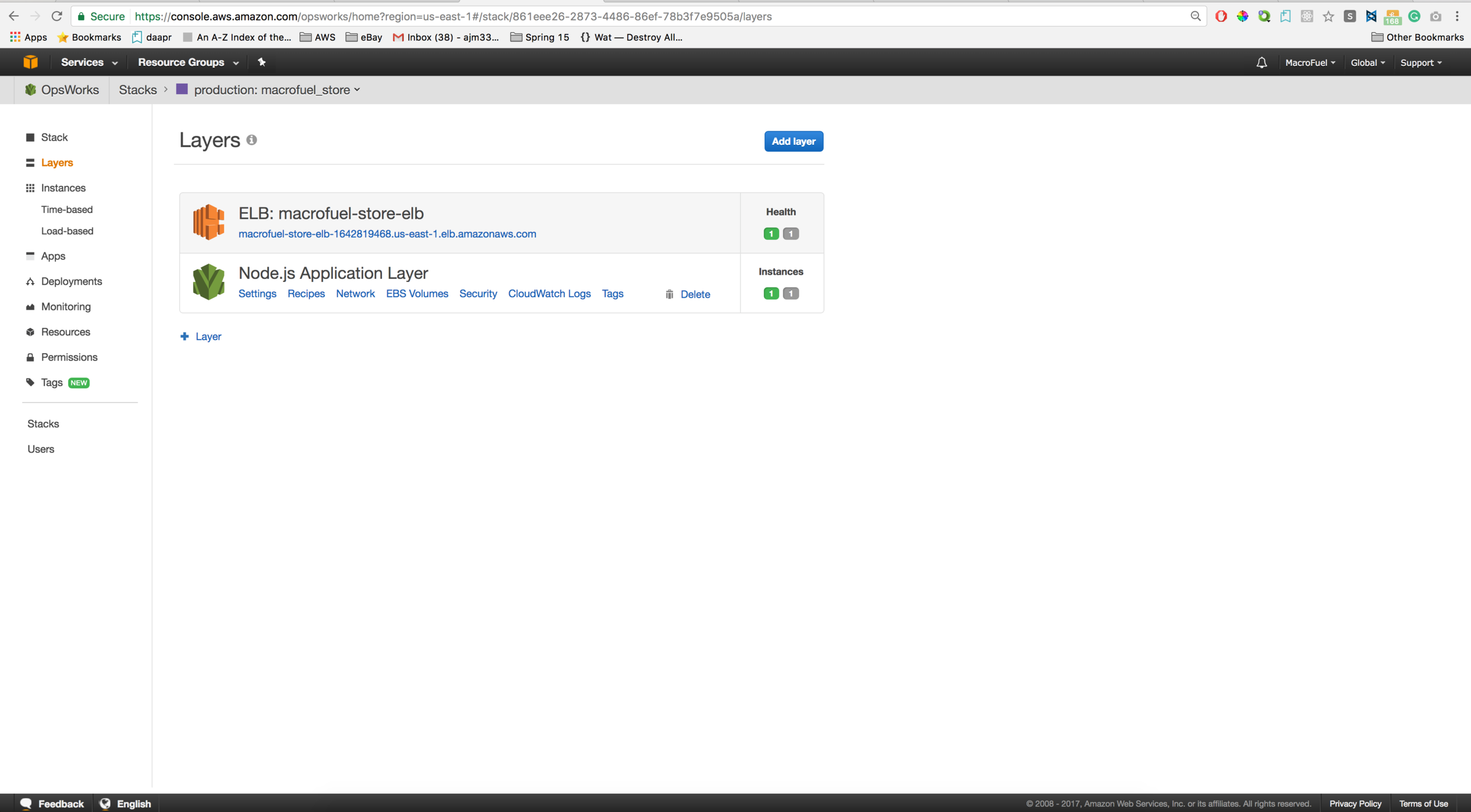

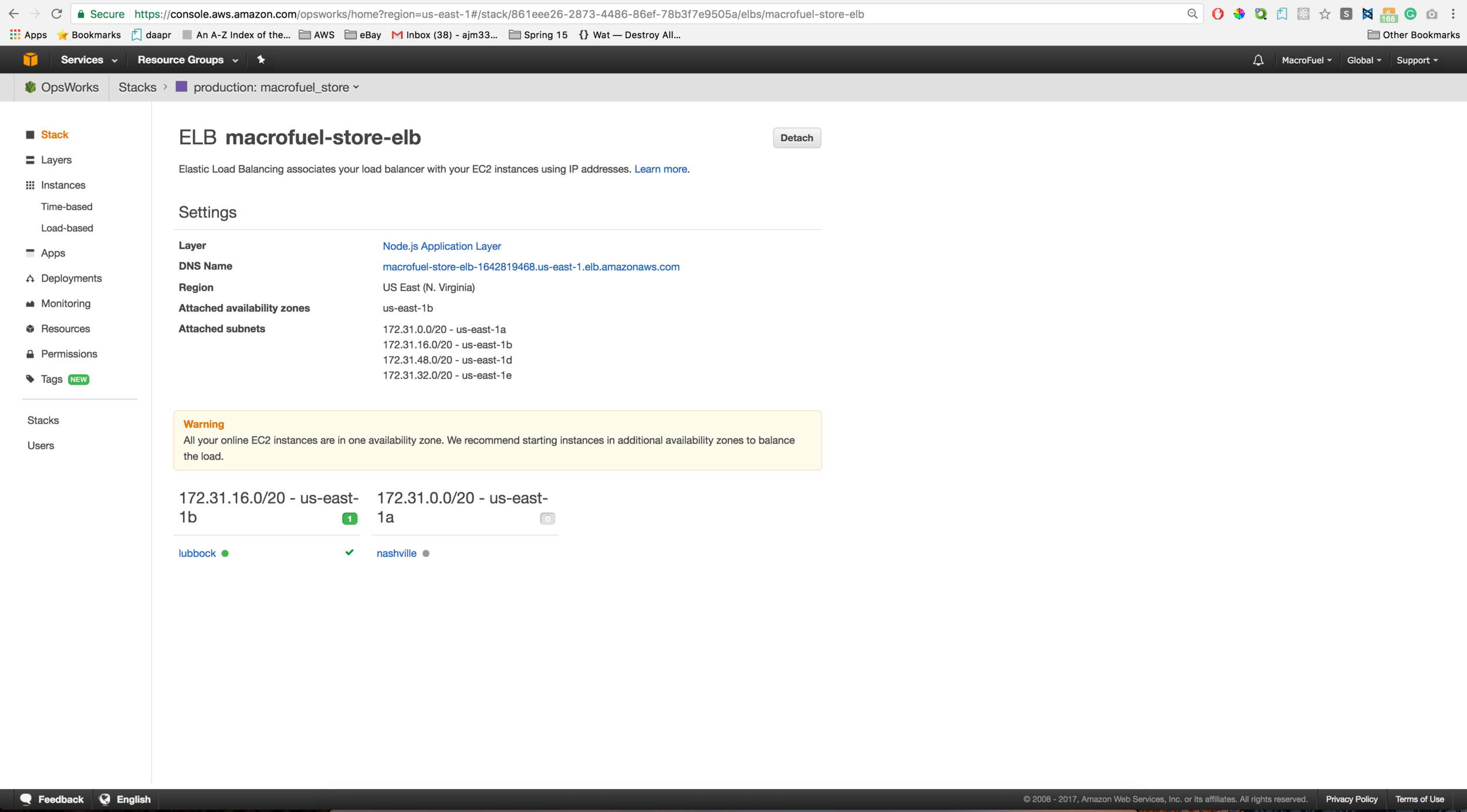

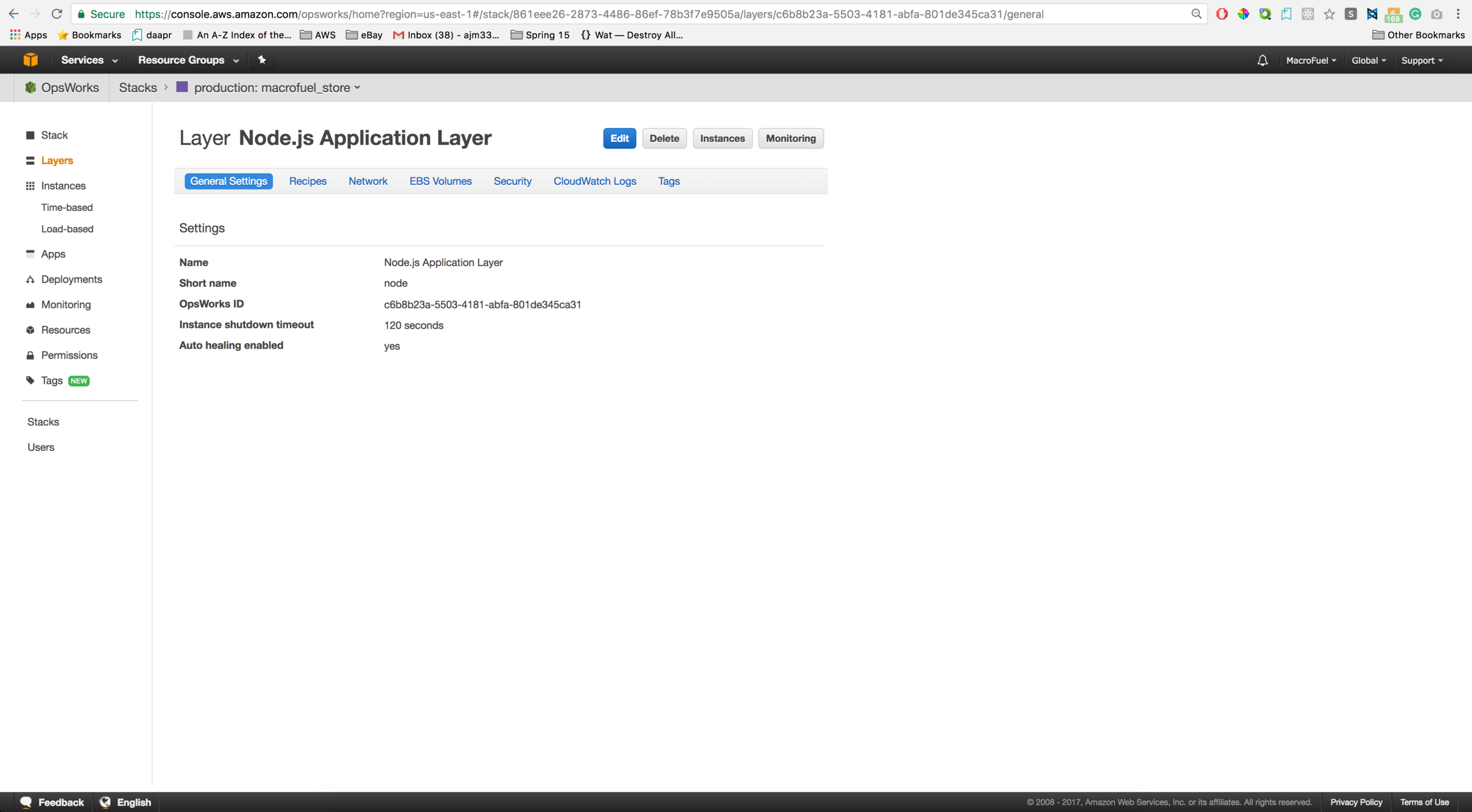

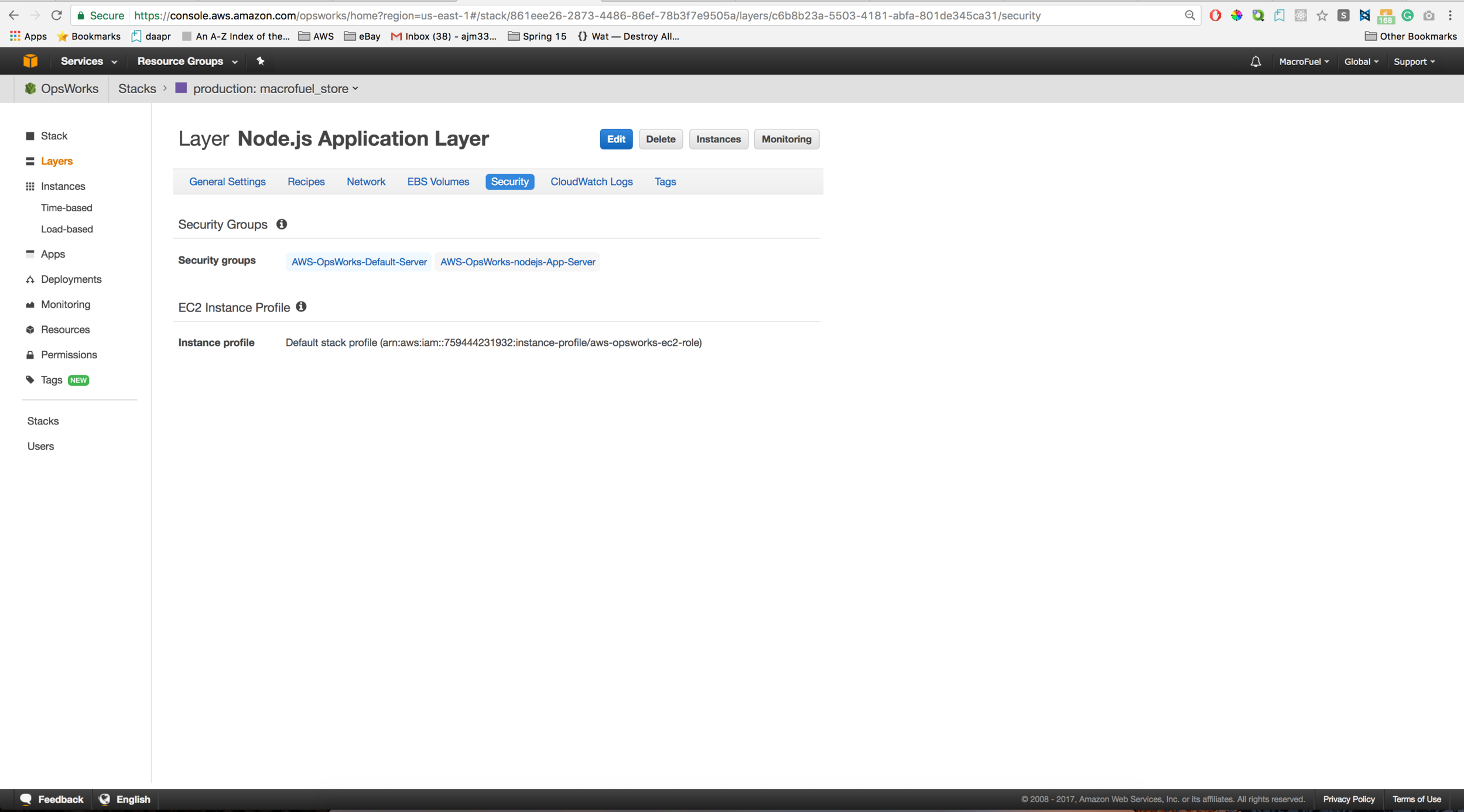

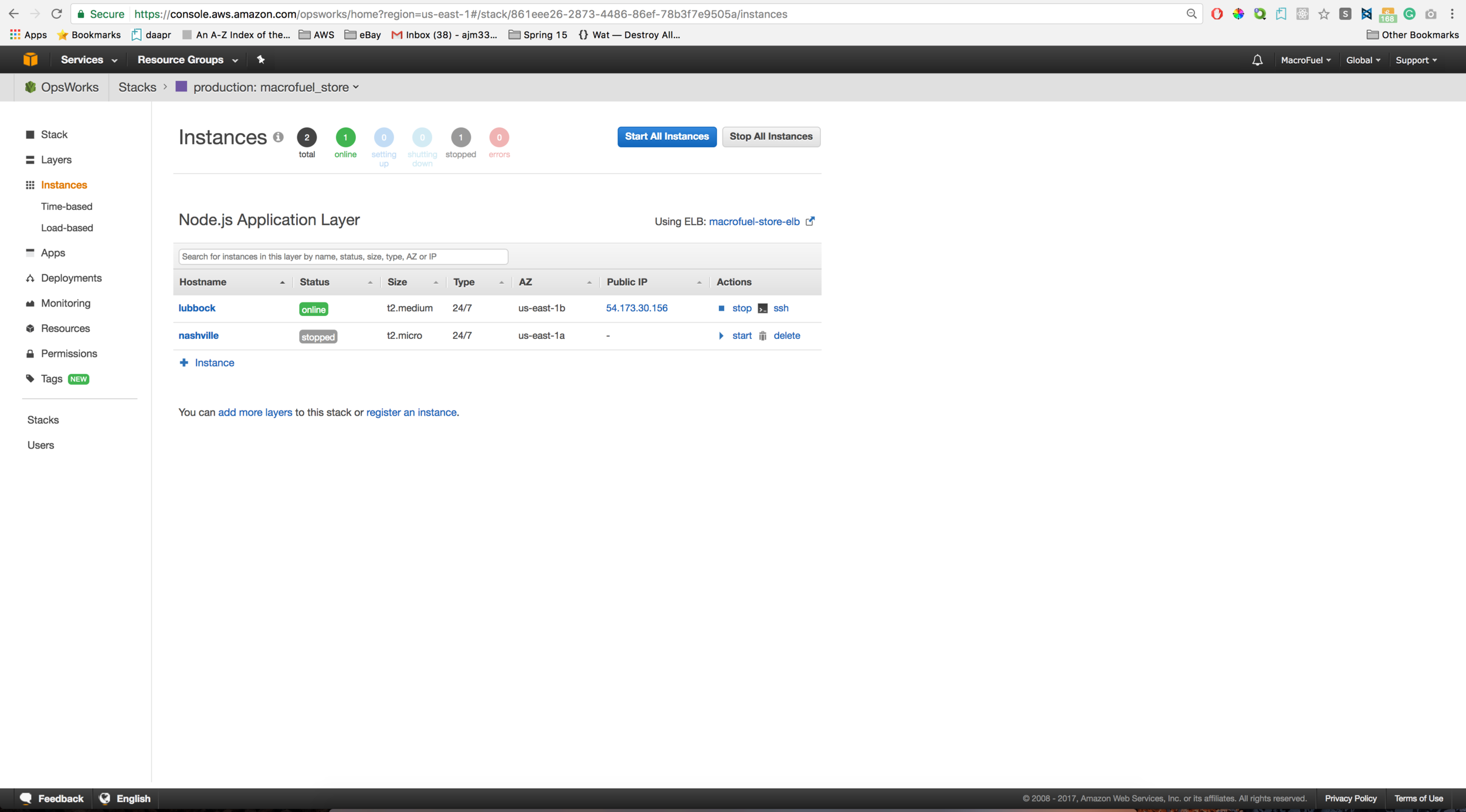

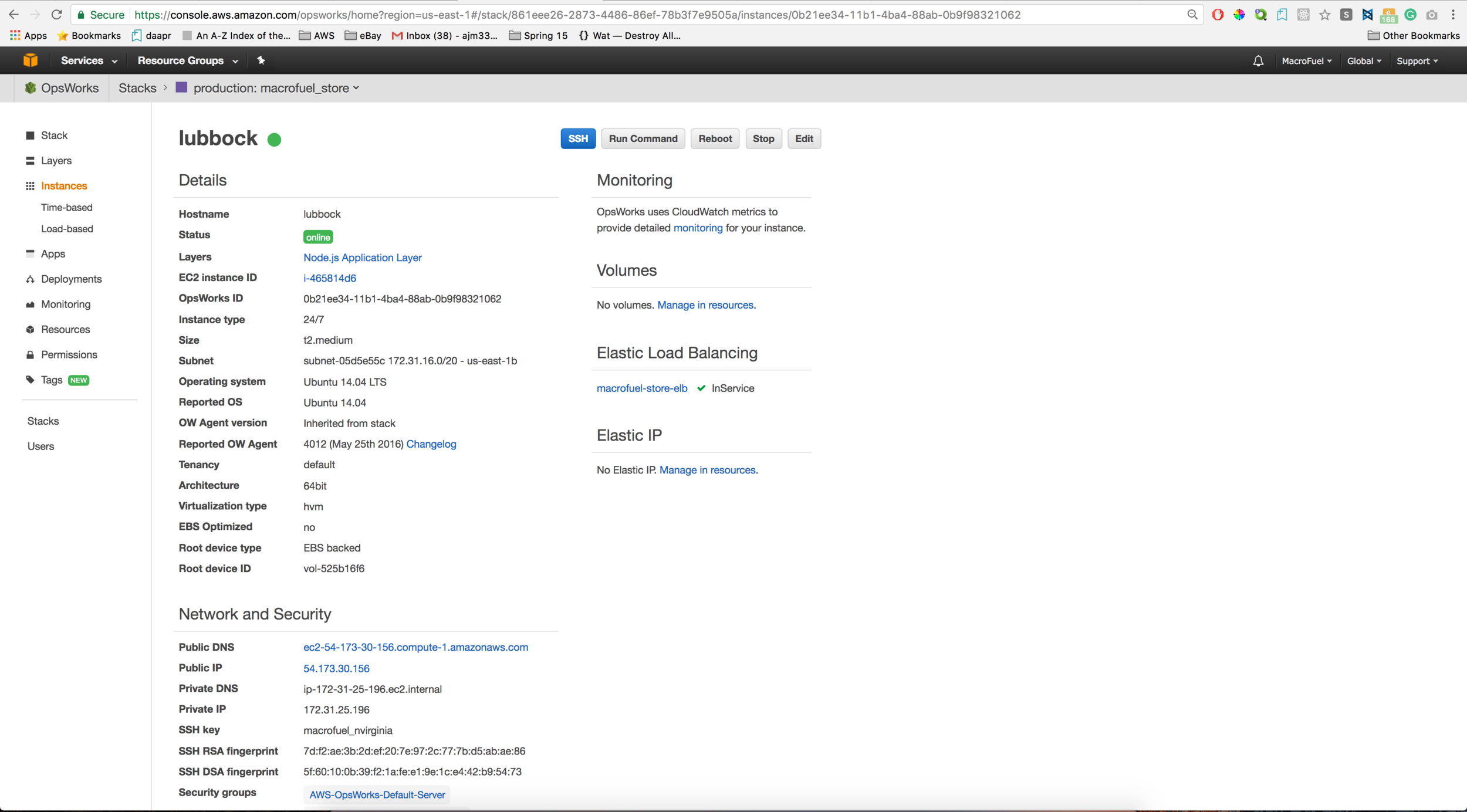

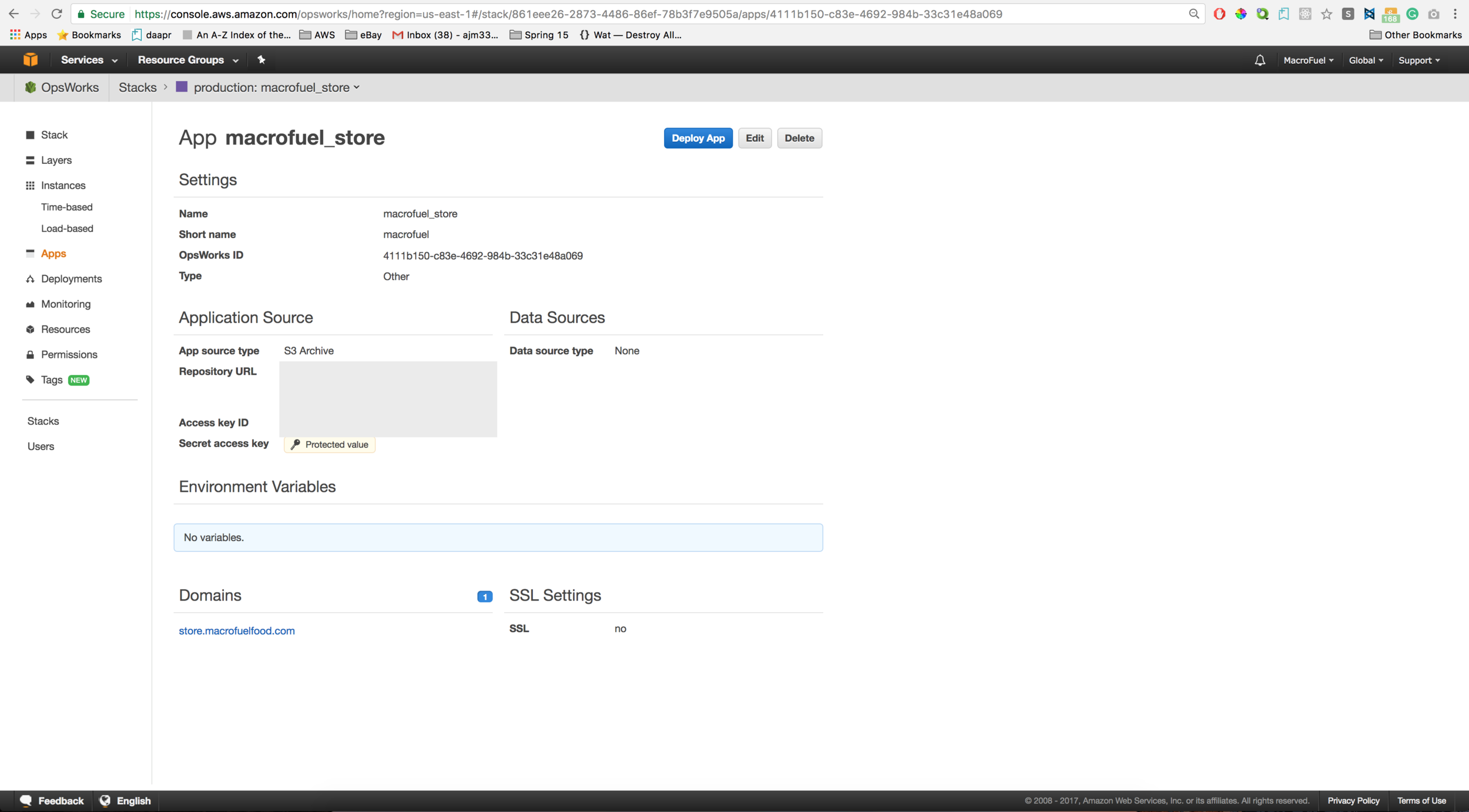

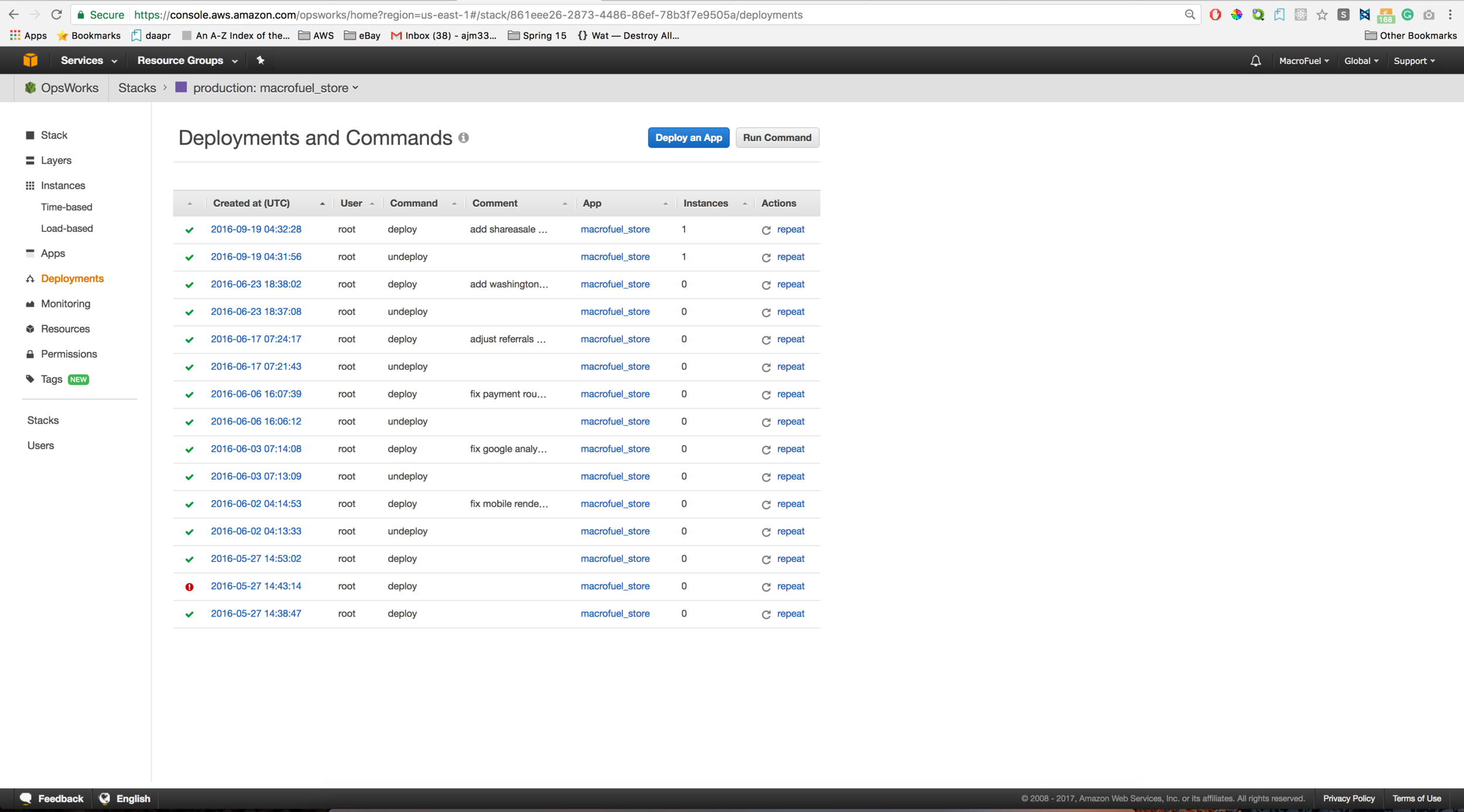

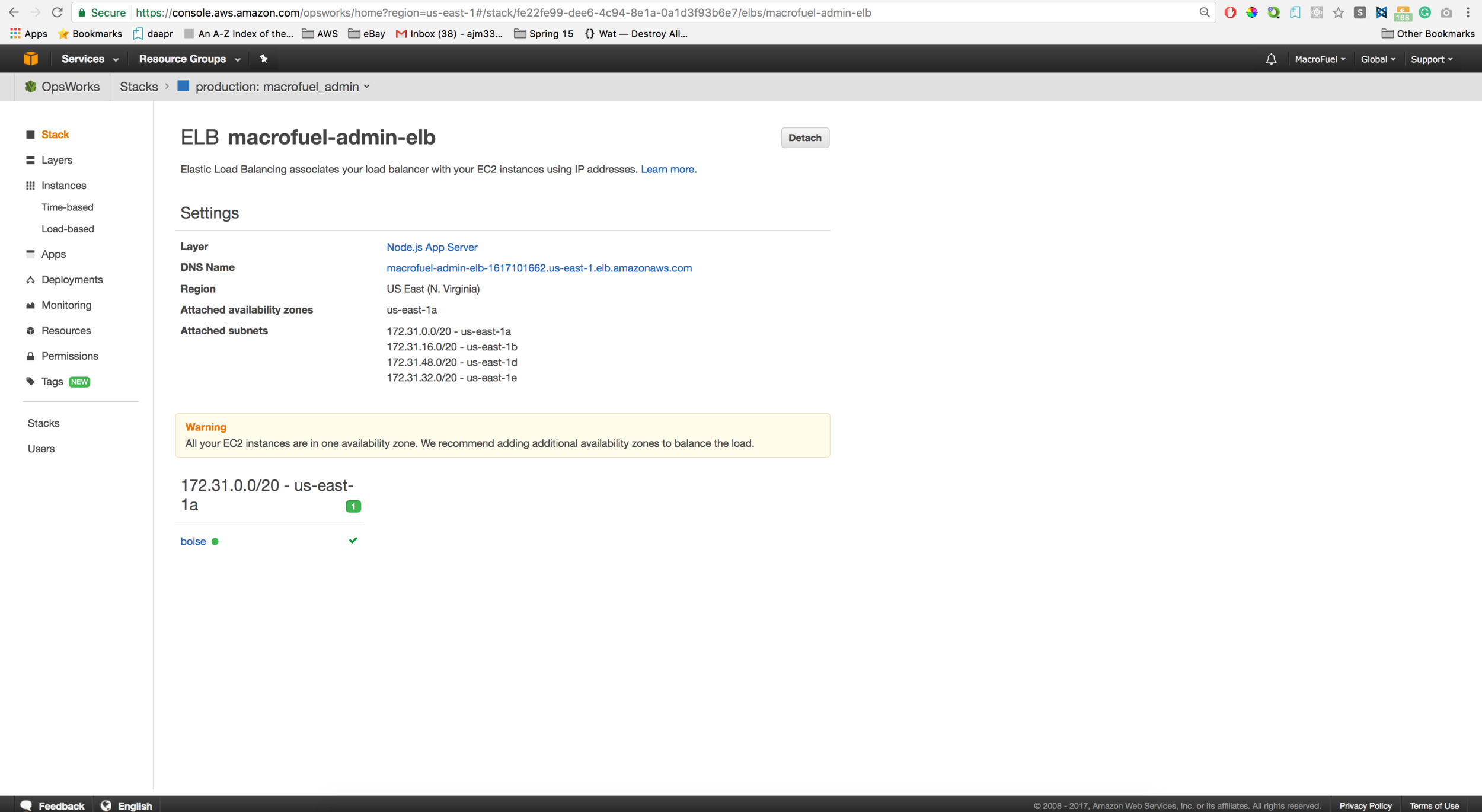

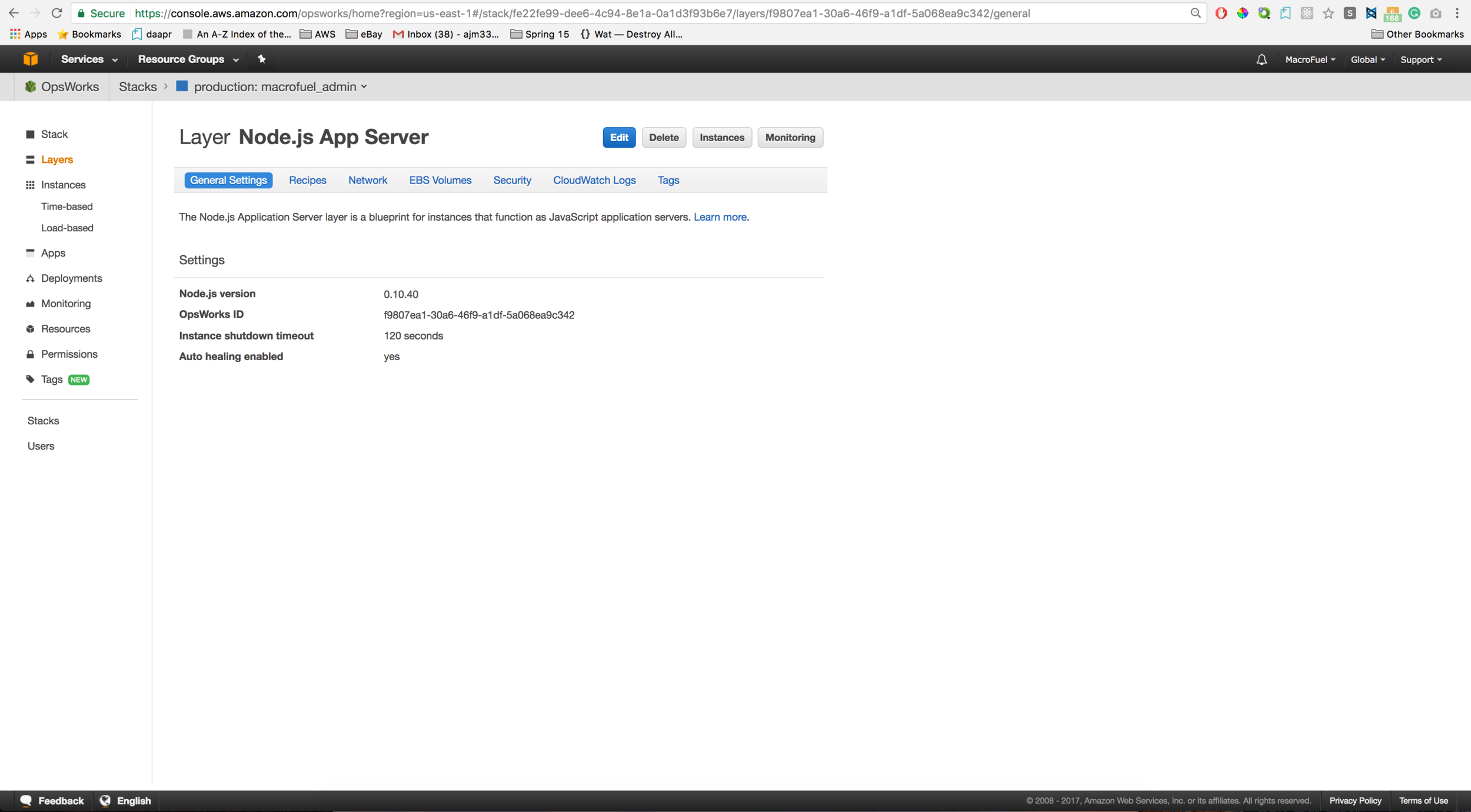

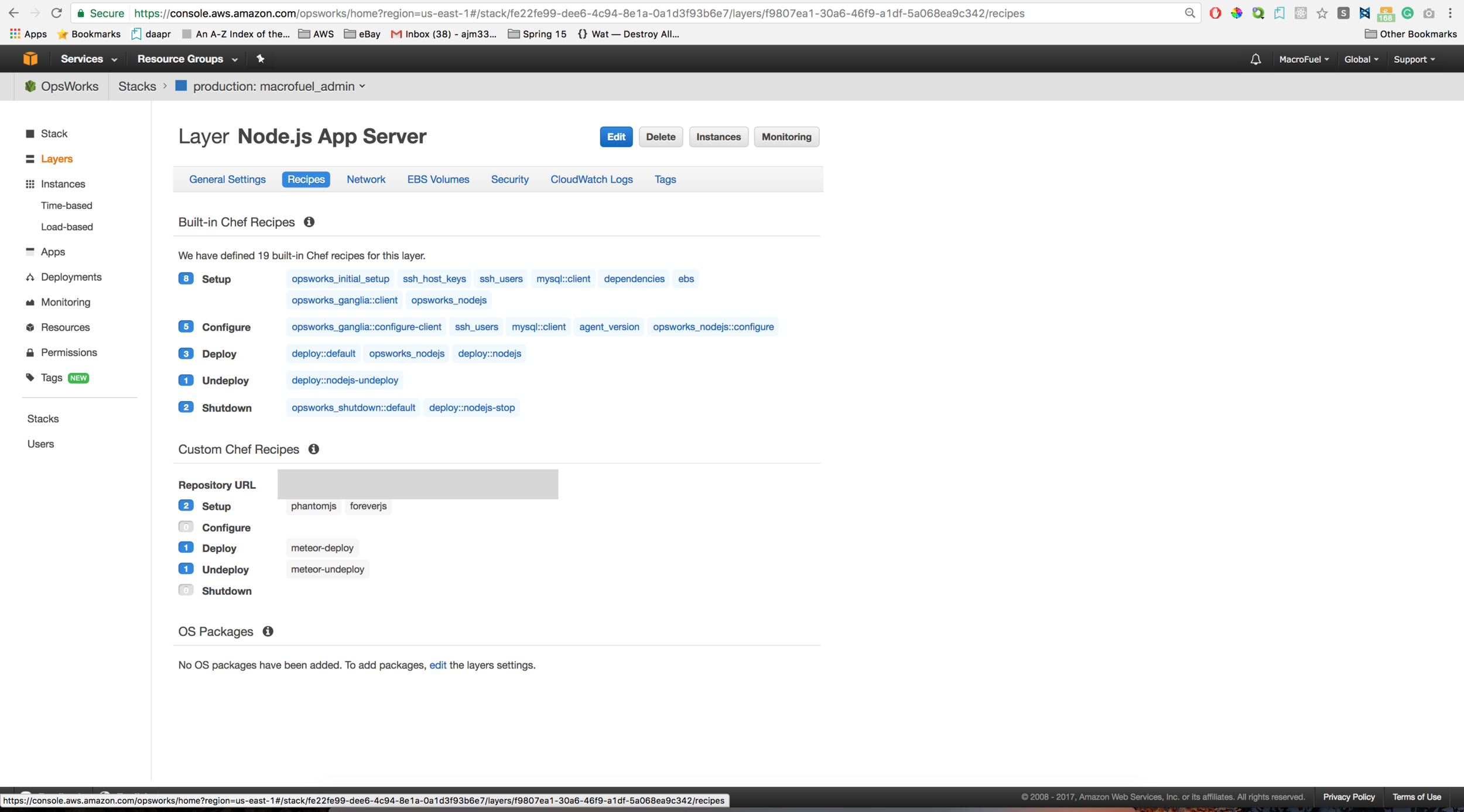

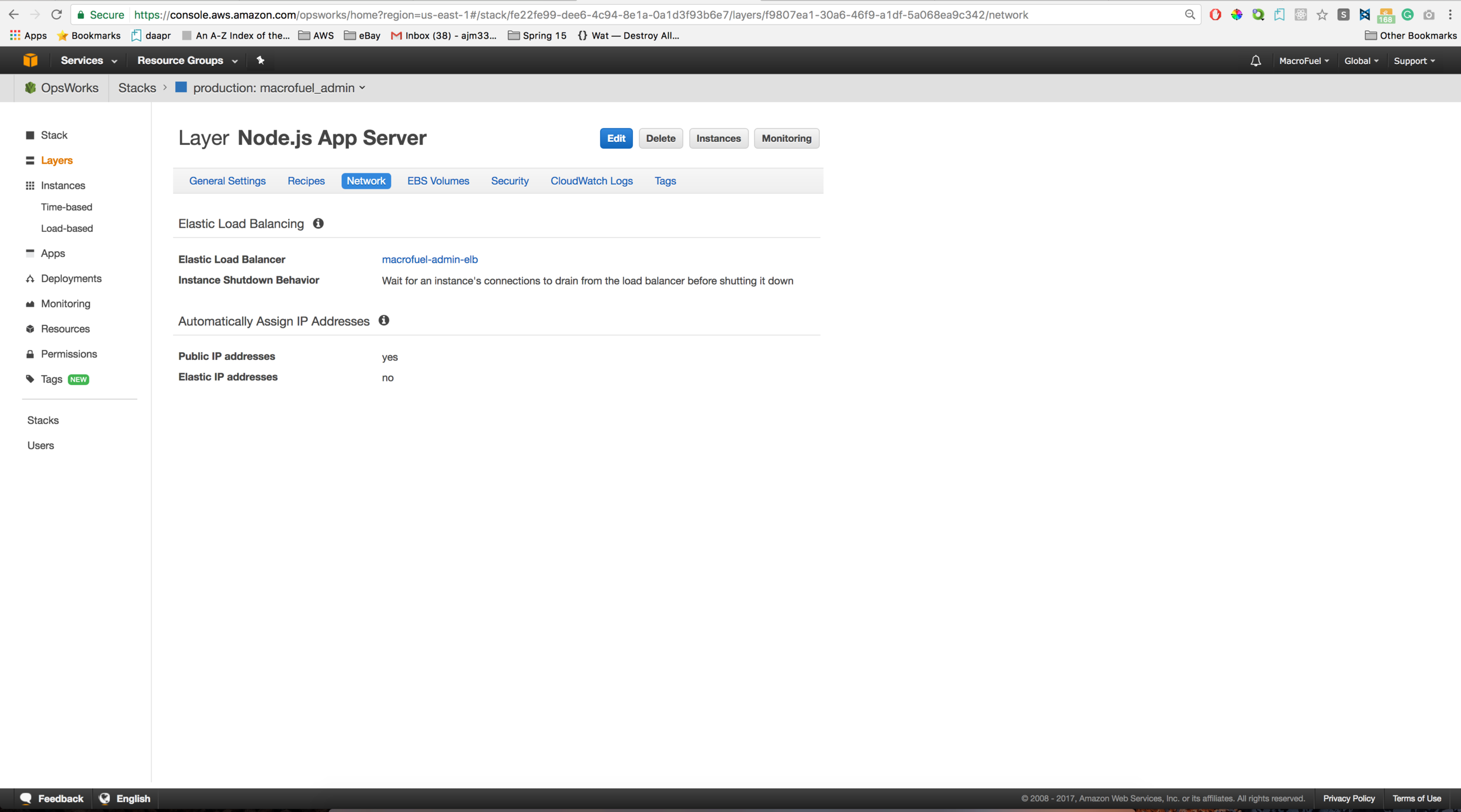

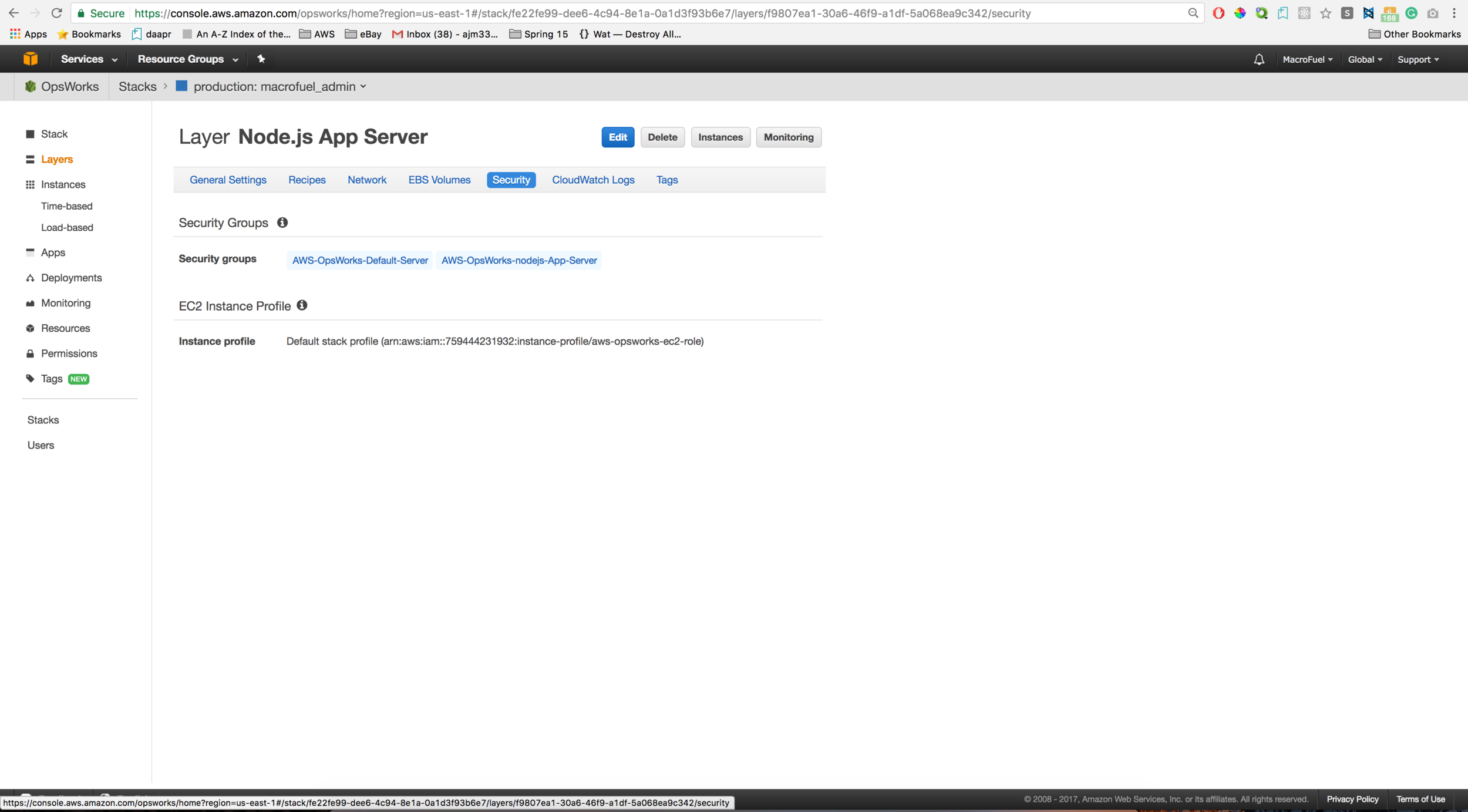

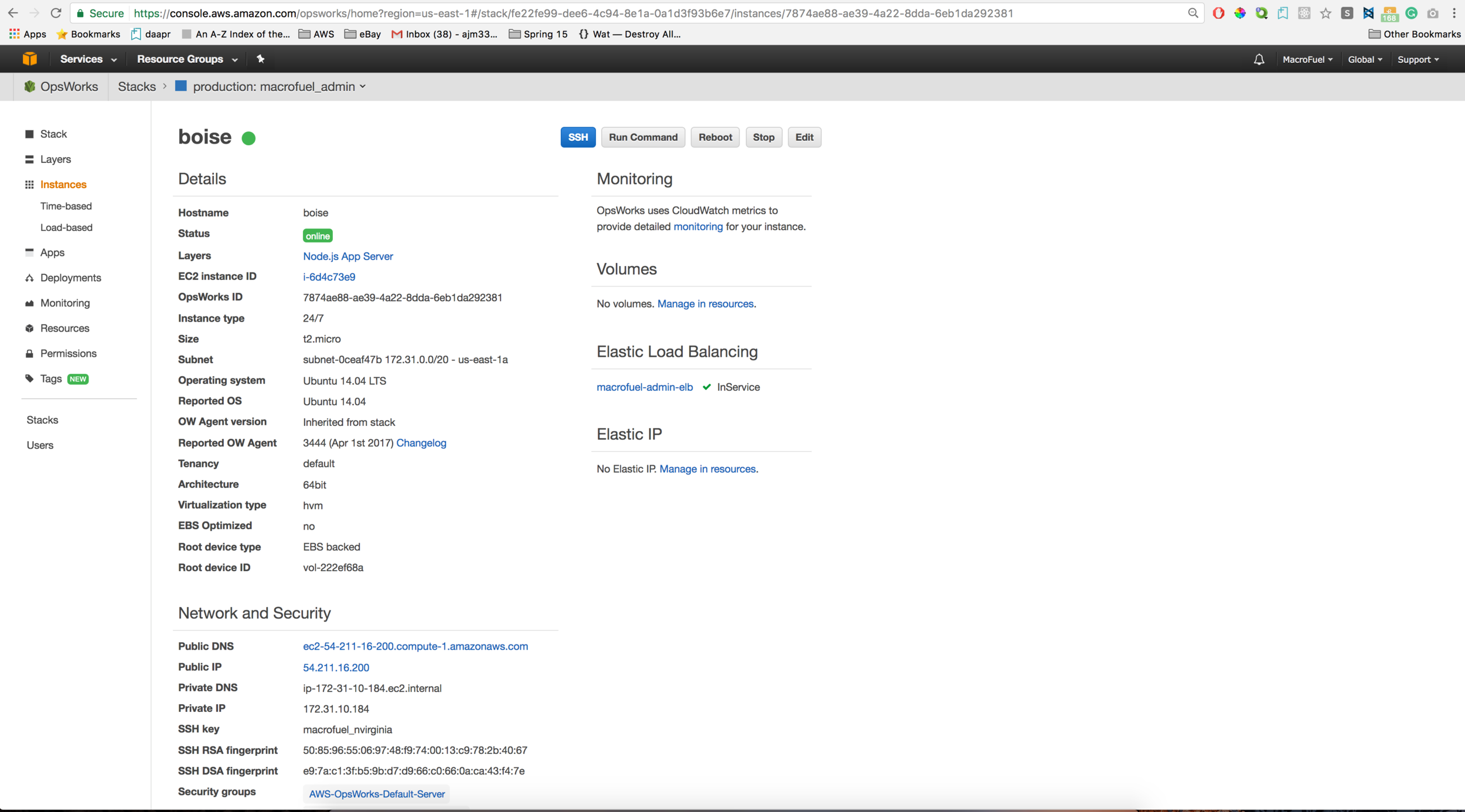

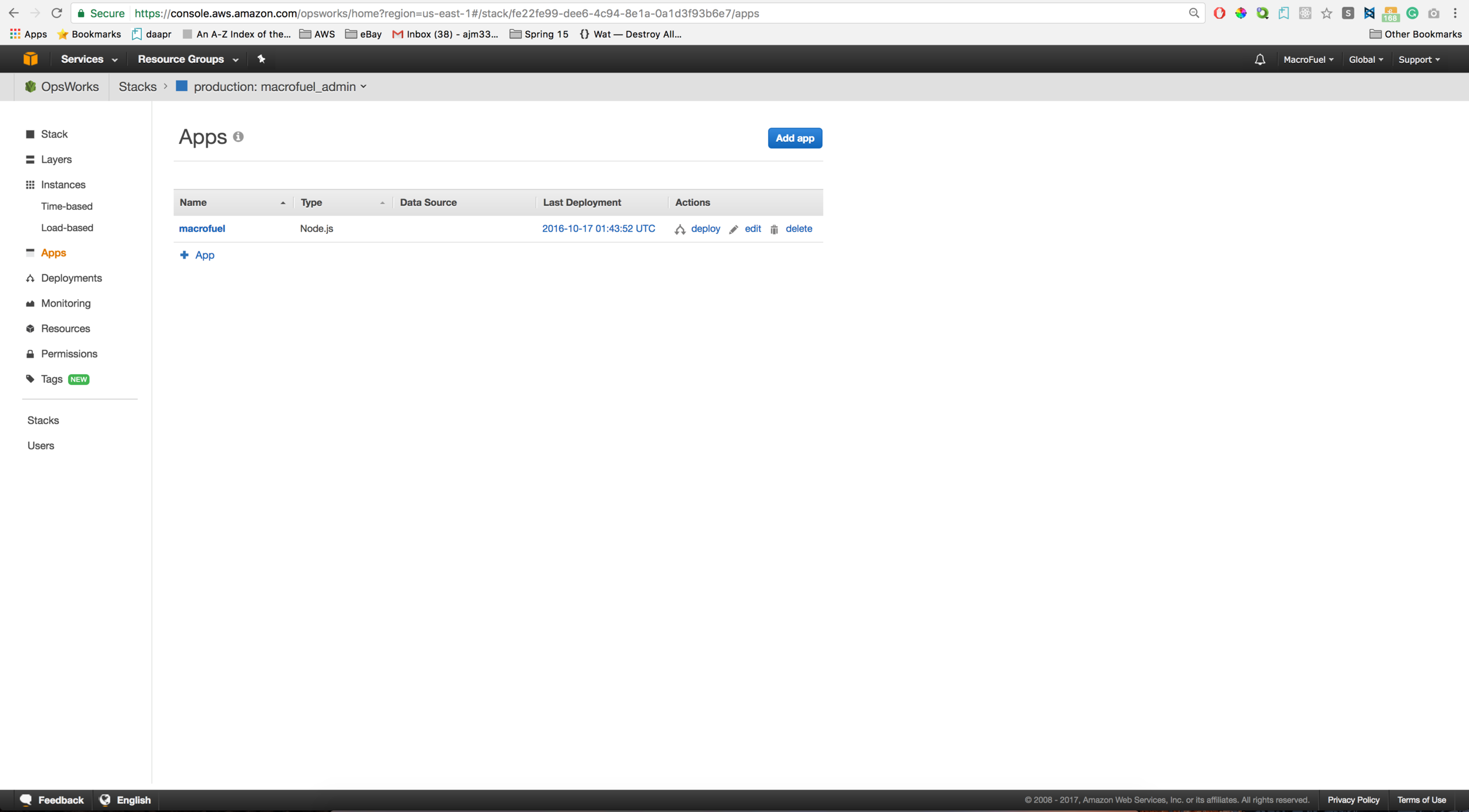

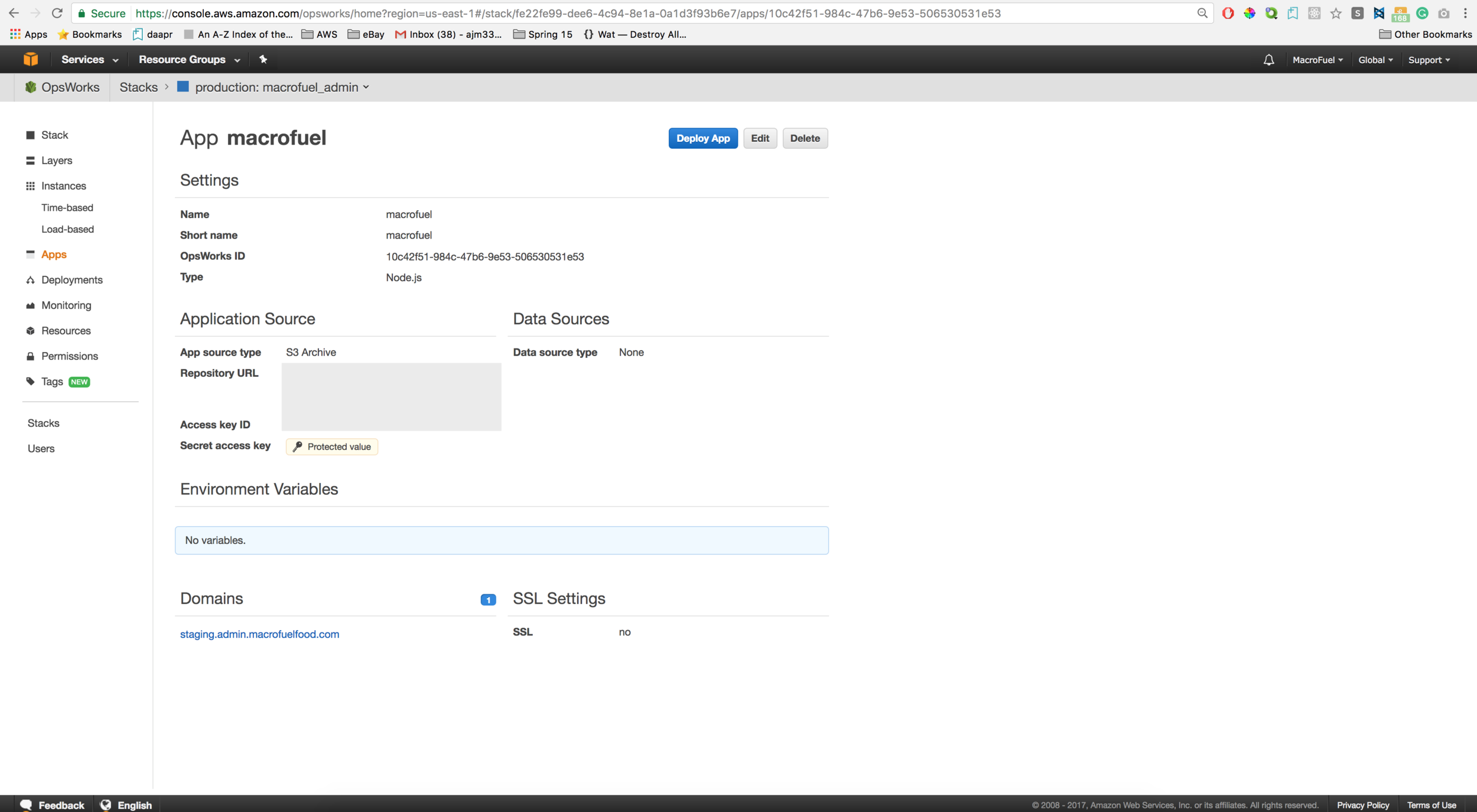

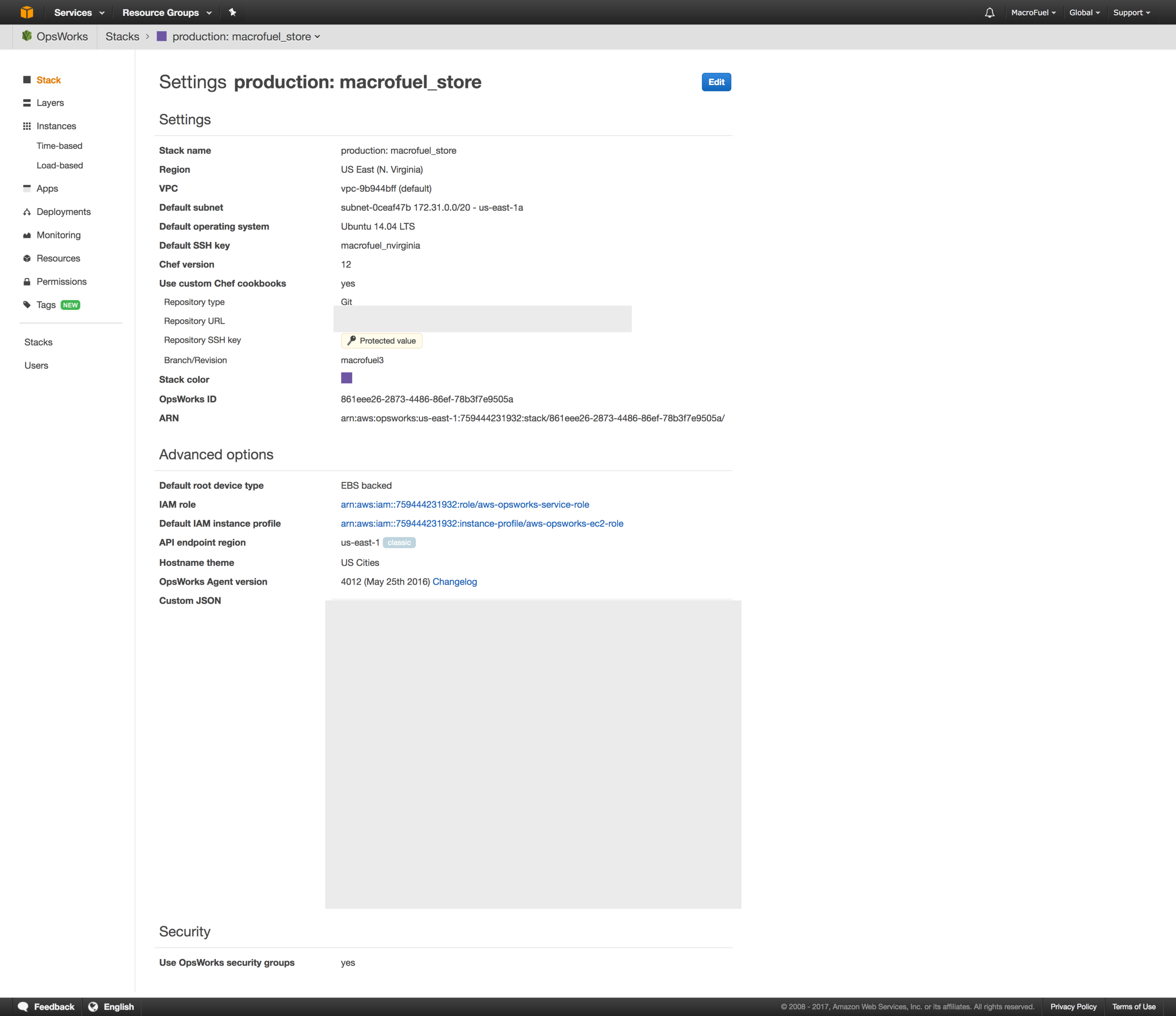

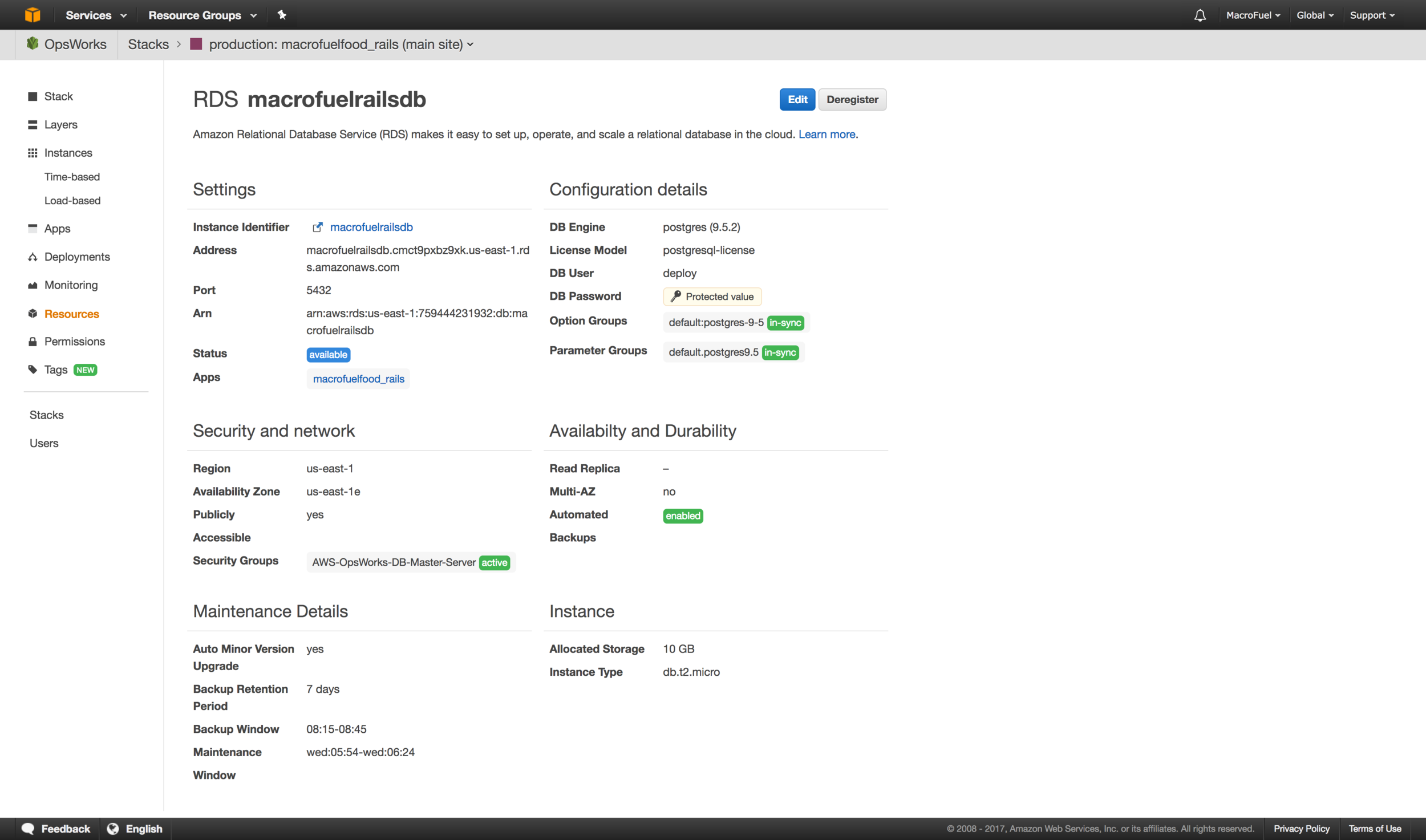

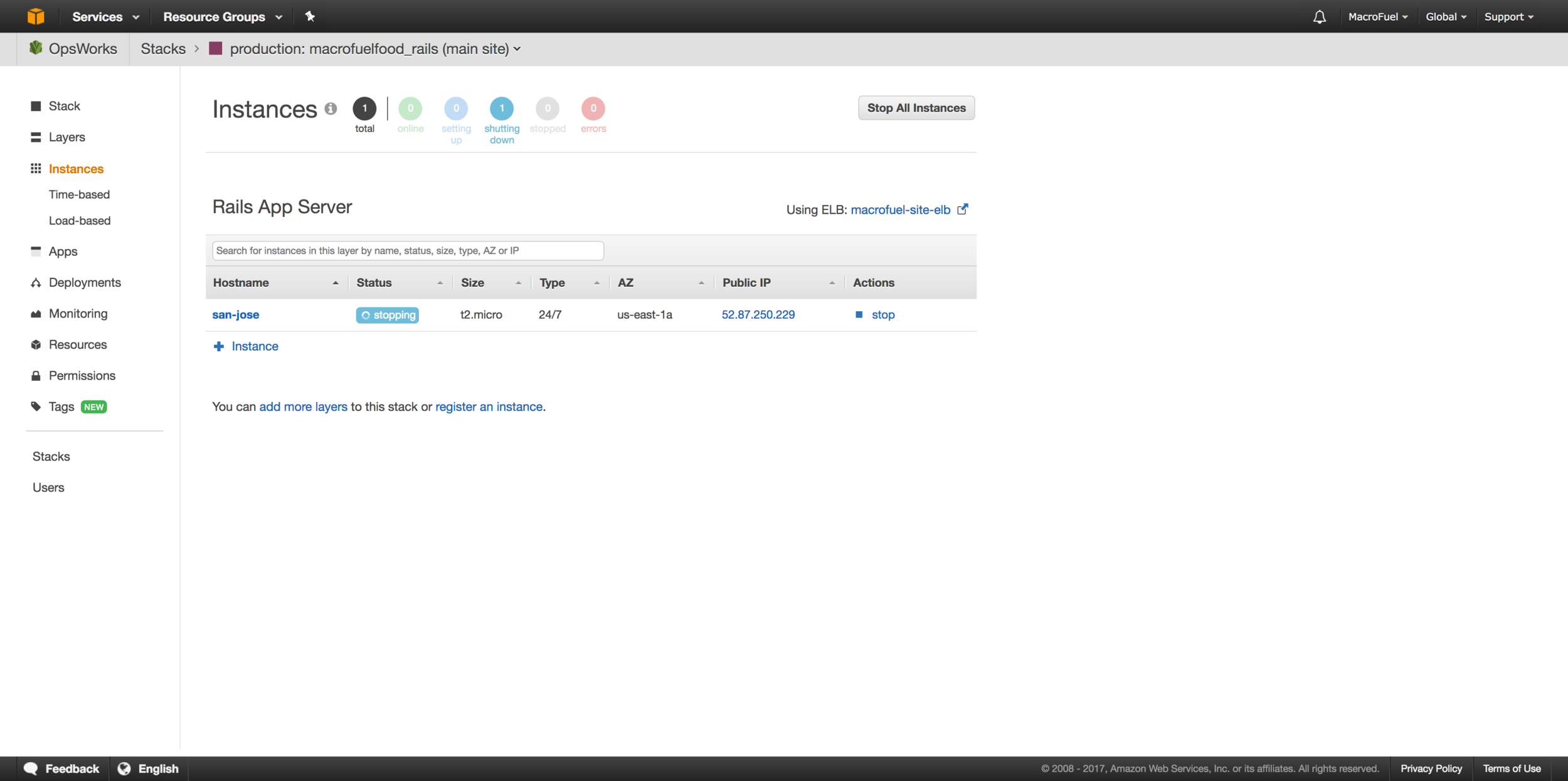

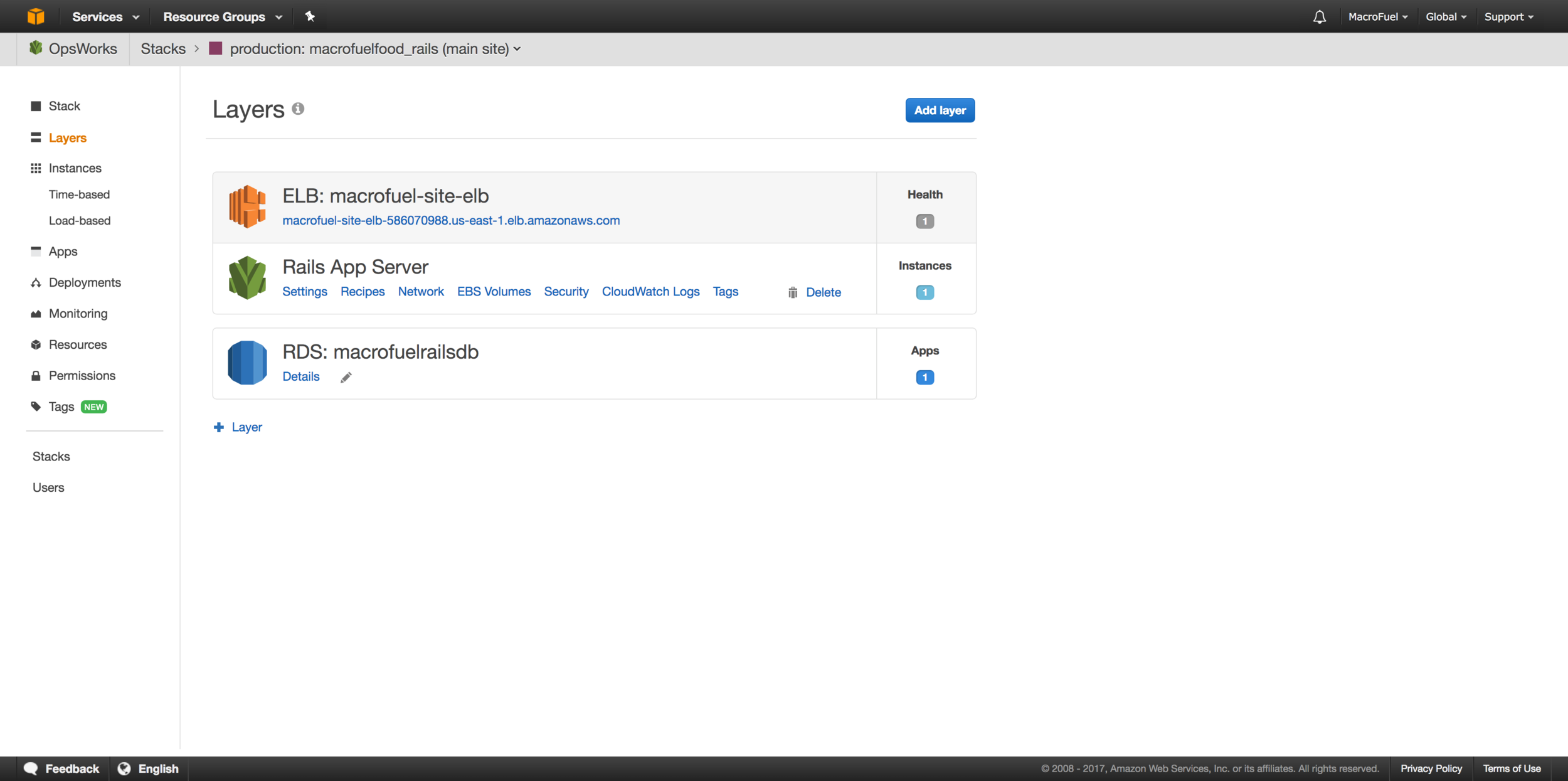

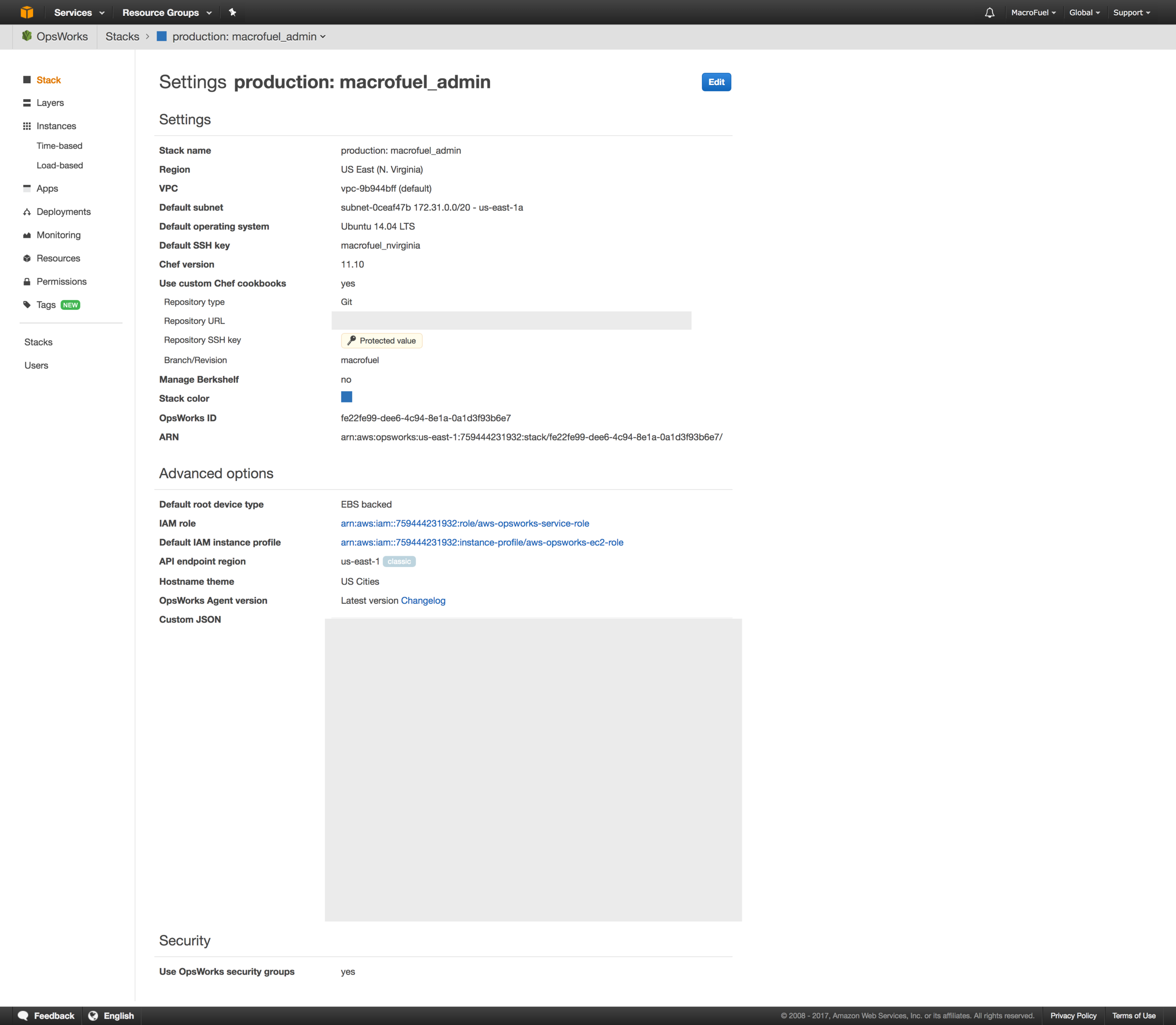

All images and other assets were hosted on Amazon S3 and served over Amazon CloudFront. Traffic was routed through Amazon ELB and server management and deployment was done through Amazon OpsWorks. The application was hosted on Amazon EC2 and the database was on Amazon RDS using PostgreSQL.

Storefront, Administration Dashboard, and Engagement Platform

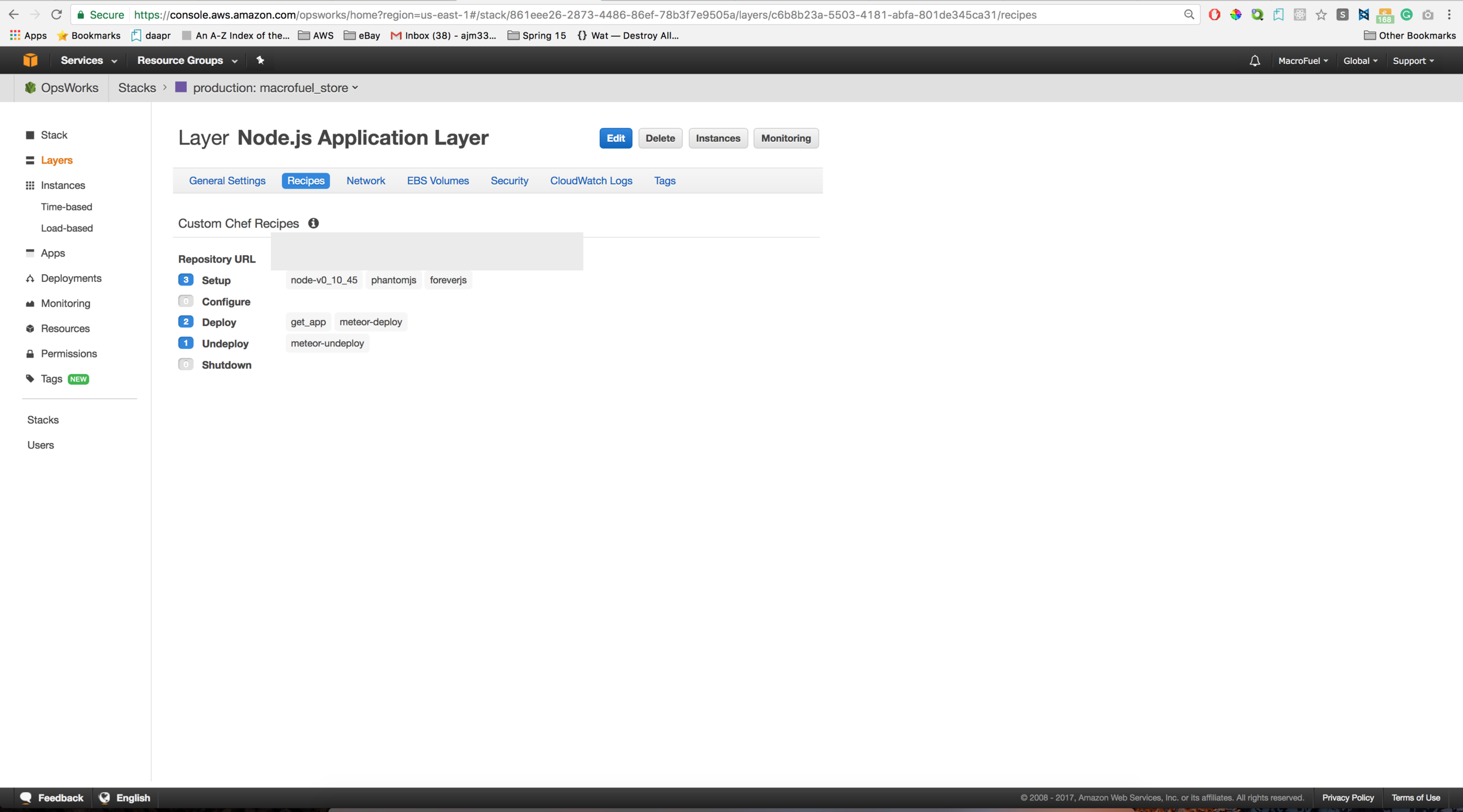

The Storefront, Administration Dashboard, and planned Engagement Platform were written in Meteor and React hosted on a combination of Amazon Web Services and Compose. The configuration was almost identical to the Rails applications, with the notable exception that the database was using MongoDB (the default for Meteor) so I flipped out Amazon RDS with Compose. I chose Meteor and React so that I could build a single application that can work across devices. Meteor has a tight integration with Cordova, which I was going to use to port the MacroFuel Technology Experiences into applications for phones. Later, I planned to use React Native to have a native experience. I also wanted to leverage Meteor's WebSocket technology with live updates for the Engagement Platform.

Each application had its own subdomain, Load Balancer, and Application Server Cluster, but all applications sourced the same database. This had the potential to be a bottleneck later down the road, but I used this configuration for a few reasons:

- Having all applications use the same database allowed me to more easily create shared user accounts across applications.

- MongoDB is a NoSQL database; it can scale horizontally, so the issues that one might face with many applications reading from a SQL database were not as drastic.

- Compose would take the burden of scaling a cluster for me (they do both vertical and horizontal scaling for their Elastic Deployments).

Learnings

Applied Learnings

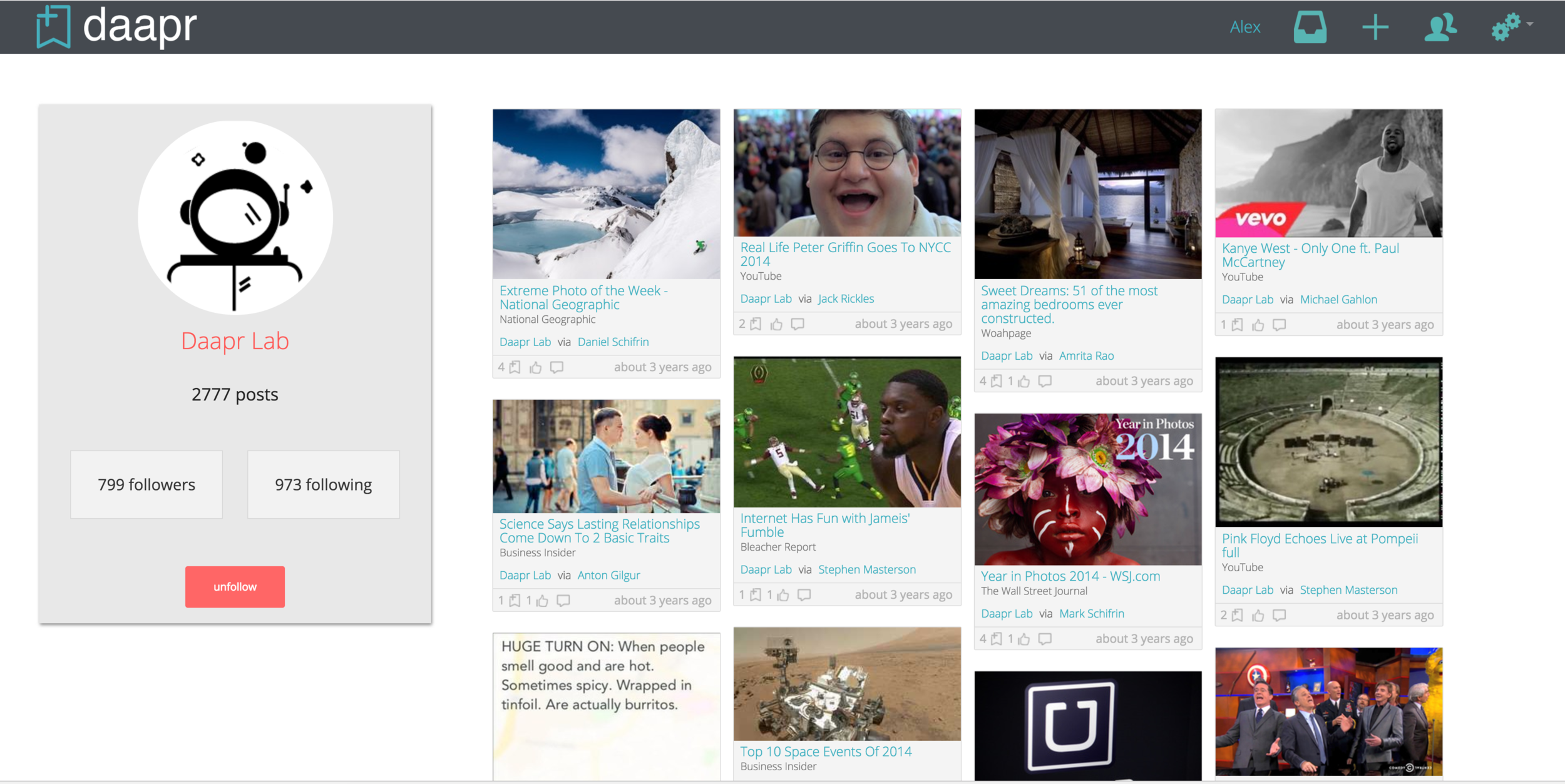

I recently wrote about my first startup, daapr, and I directly applied these specific learnings from daapr into MacroFuel:

- Build mobile first. Although we did not have a native app experience, the entire platform was built with phones in mind. The design was mobile-first, and the technologies were chosen to easily get onto phones as an application.

- Know every part of the [technology] product. This was particularly easy because I built everything by myself, but I made sure not to leave anything to chance like I had originally done with daapr.

- Don't be afraid to try new things. With daapr, I originally stayed away from technologies and problems that I was unfamiliar with. Compared with daapr, I had a better idea of what I was doing, but I made sure to make the best decisions for the technology product and not let unfamiliarity hold me back.

- Keep the team small. The core MacroFuel team was only ever 4 people. We at one point had more people contributing; however, we made sure to prioritize our energy and efforts on the company and product as opposed to scaling the team when the company did not need it.

Gained Experiences

MacroFuel was about selling a product. This was both similar and different from daapr.

MacroFuel and daapr were similar in that I was selling an idea and a vision about a product. They both required convincing customers and users to look at how they approached an activity differently. For daapr, it was changing the way users browsed and shared article/video content. For MacroFuel, it was changing the way customers approached finding and consuming quick meals. The biggest difference between these companies, was with daapr I only ever asked someone to sign-up and play with an app, but with MacroFuel, I was asking for people to give us their money.

Asking for money was a bit anxiety-provoking. This first started with the Kickstarter campaign. I felt uncomfortable at first; even felt guilty at times. I was asking people to invest their hard-earned money into me, an idea, and a company that was unproven and in unchartered territory. I was even asking people whom I knew did not have that much money to take a risk, and try our product. In a broader perspective, the ask I made was small, maybe $20-50 dollars, which is nothing compared with potentially asking an investor to put in thousands (or millions) of dollars. Raising money was a good experience for me to be exposed to and hone.

Asking for money continued past the Kickstarter. I still had to help drive sales to the e-commerce store that I built. As time went on, I became more comfortable with this notion but is not something that came easily.

MacroFuel also helped me to gain experience actually making money at a startup. Daapr was a fledgling social media company with the goal to acquire a ton of users, then monetize later. With MacroFuel, the company had to monetize now. Gaining a background of actually driving revenue from the get-go was a big change for me and a great step forward in my entrepreneurial ambitions.

Working on MacroFuel also gave me a product outside of my first personal website that I owned the end-to-end experience in all aspects. I owned the designs, the engineering, the analytics, the architecture, the infrastructure, and the product in every capacity.

Different Approaches

As I reflect on my experience with MacroFuel, there are a lot of things that I did way better than I did with daapr; however, I have found several ways that I would have done this startup differently.

- I would be more heavily involved in the business. I leaned on my partners to write, edit and update the business plan. If I were to do it again, I would get myself more involved in this process. Moreover, I contributed to the plan at a high level, gave feedback on it, and weighed in on opportunities it presented; however, I did not look at the financial models in-depth, I did not contribute to the accounting, and I did not participate in the opportunity assessment of the market we were looking at.

- I would completely re-prioritize the steps I took in the technology vision. I focused a lot on the future of the company, like how we scale our stack and increase engagement. The issue was, that we needed a customer base to start with before anything I built had significant returns. I put my technological ambitions first over the company needs. Realistically, the company did not need a custom built store and website to get started. My original gut feeling had been to use something off-the-shelf like Squarespace or Shopify, but I became so wrapped up in the technology vision that I lost sight of the fact that the technology did not mean anything at our infant stage. If I were to do it again, I would use Squarespace or Shopify for the site and store, and then focus all of my energy on Search Engine Optimization. What the company needed was to be able to find customers across the internet on a minimal marketing budget. I would have used research and data to understand what kind of content we should generate for our target customer segments, then find the ideal sources to get links from to drive traffic to the site. The company needed more traffic and customers, not bold technology solutions.

- I would more clearly identify our target customer within our team. We had originally wanted to be used by everyday folks, then young professionals, then targeted more fit individuals, then bodybuilders, then Obstacle Course Race athletes (like Tough Mudder), and so on and so forth. I personally was really in love with the young professionals demographic, but the reality was that we were not making enough sales there. Each member of the team had a different vision of who the target demographic was. It made our branding weaker, and our marketing efforts less effective. I would do a more thorough opportunity assessment at the start to best understand whom we should target. This would mean finding any data possible that could help point us in the right direction and even working to get surveys in front of more people to better understand what our customers wanted. Our customer discovery was not thorough enough, hence why we struggled to find our target customer.

In the end, I learned so much from MacroFuel, and I am glad I did it. Gus, Max, and Charles were great partners, and I look forward to seeing where they head next. I made progress on my learnings from daapr and gained more learnings from MacroFuel that I will apply to my next venture.